story and photography by JIMMY LEE

Steven Kim begins his presentation with a question: What words do you associate with gangs? Even amongst this group of youth counselors and educators at the Koreatown Youth and Community Center during a gathering last May, the responses veer toward the sensational and stereotypical: criminals, drive-bys, drugs, violence.

It’s an obvious knee-jerk reaction, especially with the images of gang members with tattoos not just covering their bodies but also their faces, flashing signs with their fingers or posturing while holding guns, being projected via Kim’s PowerPoint. But for someone like Kim, these intensely negative perceptions are just a few of the many challenges he faces in his chosen field of gang intervention. It’s as if he’s on a Sisyphean quest to find answers to one fundamental question: How do you humanize someone who doesn’t seem human?

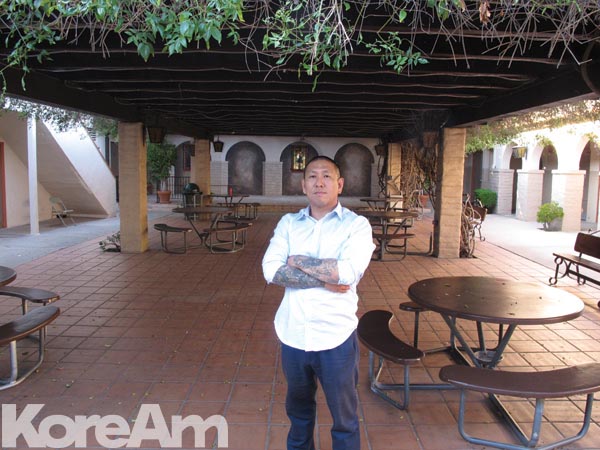

For Kim, it’s a deeply personal mission. As the executive director of the nonprofit Project Kinship, which works with the at-risk population and the formerly incarcerated, the 38-year-old Kim looks every part the respectable social worker, in his light blue dress shirt, navy-colored slacks and tan leather Oxfords. But the shaved head and the tattoos that completely adorn both arms hint at a far more complex identity.

Look even closer, and you’ll see three black dots inked just off his left eye. He got those in jail, after a prison riot broke out. “It’s just, on that day, I earned it,” by fighting on the side of the Mexicans, he would tell me later. “And it’s not like [I can tell them], no, I don’t want to get it on my face. [They’re] like, ‘You’re next.’”

But as his presentation continues, Kim elaborates on the factors that lead to young men and women joining gangs, and how more recent theories posit that early traumas are often key causes, not unlike post-traumatic stress disorder. It becomes clear that the knowledge he’s sharing has also been learned at the school of hard knocks. In fact, he’s been to the offices of this Koreatown social service agency before, but decades earlier, as a young teenager. He was mandated by a

juvenile court to attend counseling here, after breaking into a house.

At one point, the slideshow stops at a photo of a cherubic boy, holding his little sister. It’s Kim, at about the age of 9. He then asks, rhetorically, “How does a kid go from here, to here?” as the next image pops up, showing an older Kim, wearing a wife beater and long baggy shorts and standing in a defiant pose.

“There’s always a story,” Kim says.

At the Korean restaurant just across the street from KYCC, Kim starts to tell his story, though he warns some of the details of his past are sketchy. “My memory is not so good because I’ve damaged some brain cells,” he says—a consequence of heavy drug use.

Kim has a surprising affability and sense of ease about him that perhaps stem from someone who has hit rock bottom and then grew determined to crawl out of his own abyss. He speaks of gangs and the intervention work he does now with the clinical authority and confidence of a seasoned social worker; hearing himself talk sometimes surprises even him.

“In 2000, I couldn’t carry on a conversation like this,” says Kim.

He was intensely quiet back then in his early 20s, and when he did talk, imagine your stereotypical “gangsta” speak—the patois of a “cholo,” with lots of “ese” in the verbal mix. That was once his language. He first learned it on the streets of the Orange County suburb of Garden Grove, where his parents, who immigrated to the States before he was born, moved their family because of the sizable Korean population here. But on their particular street, the residents were mostly Latino, and an 8-year-old Kim had become the subject of constant bullying by the neighborhood kids. After years of subjecting Kim to abuse, one of the boys invited him over to his house. But when Kim arrived at the door, they threw balls of mud at him. It proved to be some initiation rite, and Kim finally had some friends. But in the process, as a member of this crew, the went from victim to victimizer.

You get bullied so much, Kim says grimly, that it’s not really an option not to beat up the weaker kids. “The feeling was that you get embraced,” he explains. “You’re part of the group.”

He adds, “When you grow up in that environment, with that peer group, you have to be hard, don’t let nobody push you around.”

Meanwhile, his parents, who both worked for the U.S. Postal Service at the time, were also getting harassed: Their house was graffitied and the windows of their cars broken. “It was bad, the race and discrimination they faced. I didn’t really understand that,” says Kim. Overwhelmed with just trying to get by, the couple worked long hours and therefore were often absent. So Kim found more and more ways to get into trouble.

When he was about 12, his parents were able to move to the upper middle class—and predominantly white—community of Anaheim Hills. “You take the kid out of the environment and you plant him in another environment, theoretically things should change,” says Kim. “But if [you] carry over the culture, and not have the same wealth as everybody else, then you know you’re really different.”

Even in this new setting, Kim gravitated to some of the Latino kids who were being bused to school. “Fights immediately occurred there between rich and poor,” he says. His parents started taking him to a Korean church in Irvine his junior year of high school, and it seemed to work. “Nice church kids, and they embraced me,” Kim says. “I was a church project, maybe.”

He graduated high school and then attended community college before transferring to the University of California, Irvine. He seemed to be on the right track, but Kim says he somehow didn’t feel at ease. He has trouble articulating why, settling on the words: “I never quite fit in.”

He contacted his buddies from his Garden Grove and Anaheim Hills days, some of whom had become gang members, and even invited his old best friend to move into his apartment and helped him get a job. “When I made that call to my old friends, I immediately fell back into this place of belonging and comfort,” says Kim. But they would introduce something new that would precipitate a whole new set of problems: meth.

“I tried it and got addicted, and got propelled back into, really this time, the streets and started to get involved with drug dealing, with serious violence,” says Kim.

That included running with a gang. And there would be the proverbial “drug deal gone bad,” with bullets being fired at him. “The worst was in 1999. I was completely addicted to drugs, weighing 120 pounds, and on the run from the police,” he recalls.

UCI kicked him out of college, due to failing grades; his parents kicked him out of their home. “I tried to burn the house down. All kinds of crazy sh-t,” says Kim. “Being a drug addict, I’m irrational; I’ve been up for 20 days.”

Plus, he wasn’t alone. He had met a Latina woman named Priscilla and got her pregnant. “We were homeless, living in motels, drug-addicted,” Kim says. “We were on welfare, we had no money.”

They also had no hope.

“That’s why we named [our daughter] that,” says Kim, “because literally we were so hopeless.” Hope Cheyenne Kim was born in 2001.

* * *

The moment when Kim realized his life had to change is seared into his mind. He was back in prison for about the 10th time—he’s lost exact count, but most stays were for drug possession and dealing-related charges. “My baby mama—she’s my wife now—and my daughter come in; she’s still a baby.

She’s looking at me and I’m looking at her, and she picks up Hope and pushes her against the glass. And I’m going, ‘Oh, man,’” says Kim, who was about 25 at the time.

“I remember that day I started … feeling,” he adds. “The whole name of the game had been not to feel; when you feel, it’s weakness. I go back to my cell and I start crying under my blankets.”

The court would eventually offer him, instead of prison, a six-month residential rehab program through the SalvationArmy.

He finished it. “I’m a person of faith, so I started connecting back with God and people who love God who were able to support me,” recounts Kim.

UCI took him back, too. But he was also in need of money to support his new family, and the only job he could find was as a janitor for the Salvation Army. “I sat in class and wrote every single word down. I got a tutor. I had no friends, so I would just go to the library, eat my sandwich. And at night I would pick up trash,” Kim says.

He would graduate from UCI in 2004 with a degree in criminology and then earn a master’s in social work from the University of Southern California two years later. Despite these degrees, he could only find menial labor work, primarily due to his criminal record. But he remained determined; he knew what he ultimately wanted to do was work with youth in a social service capacity.

“I just plugged away, and [met] some mentors and professors who took me under their wing,” says Kim, who was entering his 30s. “Still, I was real raw, and I just hustled, kept begging people for jobs. ‘I’ll clean your floors. I’ll do whatever.’”

A UCI friend named Jesse Cheng who was working on a doctoral dissertation about the death penalty recommended Kim for a job as a mitigation consultant. This is a role on the defense team of someone facing execution.

“Basically what a mitigation consultant does is understand mental health, understand culture, and is able to navigate into the world of the people you interview and research,” says Kim. “If they’re from a different country, I’ll go there and interview those families and come back and create a picture to explain what happened to that individual,” so that the convicted is ultimately not given a death sentence. He traveled to Tijuana, Mexico, for a case involving a member of a drug cartel. He went to South Korea as part of the defense for a Korean American man who killed his ex-wife, two of her children and her brother.

“His passion [for his clients] shows,” says Jennifer Chung, a deputy public defender who assisted Kim in the Korean American defendant’s case and made the trip with him to Korea. “He goes above and beyond the call of duty.”

Chung wasn’t sure what to expect when she first heard of Kim from her co-workers: a fellow Korean American who was once homeless, and a former gang member and drug addict? But her wariness soon changed to a sense of assurance and trust upon meeting him. “I respect Steve because—” and here Chung pauses to interject, “I’ve never been to jail, I never had a substance abuse problem. Would I be a lawyer if I went through all that? Probably not”—before continuing, “He’s been there. He took action and turned his life around. And he doesn’t apologize for his past. He’s become someone people look up to.”

Another admirer of Kim’s accomplishments is Robert Hernandez, who works with gang members in Los Angeles and is a professor at USC’s School of Social Work. The men were both graduate students at USC when they met, similarly interested in assisting vulnerable youth populations. And when Hernandez was tasked to create an undergraduate course on adolescent gang intervention, he immediately thought of Kim and got him on the phone. “I was like, ‘Would you like to work on this with me?” recalls Hernandez.

“Steve and I thought it was really important that we humanize [gangs] and not create just some Gangs 101 course, discussing deviant behavior,” he says. “The class is really going beyond the symptoms, the tattoos, getting beneath the surface, and really looking at the root causes of this challenging issue and attempting to look at solutions.”

The fact that Kim has lived the life also lends credibility to the lectures that he would give. “He’s able to add a whole other dimension to the curriculum that gets to some of the root causes, and by that we’re able to really delve deep and talk about a lot of the variables, such as trauma, grief and loss,” says Hernandez.

“And that’s based on anecdotal cases and scenarios that he would provide and share with the class.”

Hernandez adds, “He represents so much—that change is possible, that transformation is possible.”

Here at a church in Santa Ana, the three females and seven men gathered on this Monday evening in June are holding on to that very idea: That change is possible for them, too. They are all former gang members, all Latino, ranging in age from their 20s to 50s, who come regularly to this healing circle, a kind of support group led by Kim, who is their counselor and mentor. They hope, as he did, they can also turn their past transgressions into meaningful lessons.

One of them is a 30-something Latina whose name we’ve been asked to withhold. Growing up without a mother, she recounts for the group the moment when her drug-using father pointed a shotgun at her head. She also describes how she ended up hanging out with a Crips gang in Orange County, smoking and eventually selling crack. “I ran amok in Santa Ana,” she says, a trip that ended in prison. Now she is involved with Project Kinship to help deter others from the gang life (she also works with the Orange County Department of Education as part of its gang intervention efforts).

“What’s so powerful is that we come from places without hope,” Kim tells the group. “And now we are all survivors. We hold an amazing power and privilege.”

Most of Kim’s energies are now being directed toward Project Kinship in his effort to change the lives of gang members in Orange County—and yes, there are gangs in the land of “real” housewives. His last mitigation consulting job, for the time being, ended earlier this year. He plans to return to USC this fall to teach a graduate course at the School of Social Work as an adjunct professor. Long term, Kim is committed to helping those “who are in a place of hopelessness, to find a place with a future worth living for.”

“I know that sounds cliché, but you really have to believe that in this [line of] work,” he says.

Started just last year, Project Kinship is a social service still in its infancy, offering traditional programs, case management and support groups such as the healing service, as well as outreach and tattoo removal for gang members. But Kim’s vision for the organization is to be like Homeboy Industries, the groundbreaking nonprofit founded in East L.A. by Father Greg Boyle. Homeboy not only provides standard services like counseling but also social enterprises, such as a café, catering and food products that provide jobs to help turn around gang members’ lives. “The way Homeboy views the demonized—that’s what makes them great,” praises Kim. “It’s their approach, the heart that they have for people. That’s why we went with the name Project Kinship, because we really value Father Greg’s belief in kinship.”

“I would say he’s trailblazing out there [in Orange County] in bringing in a whole other community-based intervention approach through Project Kinship, which they haven’t really seen before,” says Hernandez, of Kim. “I can’t even explain how valuable he is to the movement.”

It’s been a long, tumultuous journey for Kim, from “chubby wannabe Mexican kid” to anti-gang leader. Kim, who turns 39 in December, admits old temptations can still linger.

“Those wounds are still there,” he says. “They’re healed, and more harder to break through.”

He and Priscilla, who has undergone her own transformation and now works in banking, have had a second child, 6-year-old Noah. And they live a typical family life in Anaheim Hills, of all places, with his parents’ home close by. “I’m too far into it,” says Kim, speaking of this second-chance life that he’s built. “There’s too much at stake.”

But the empathy he feels for those entangled in the world that almost ruined his won’t go away. Kim says he knows of some reformed gang members who want nothing to do with their pasts. “But for me, to come through drug addiction and all that, and to have people help me, I knew I wanted to go back, because you have a lot to offer,” he says.

There will always be those who say gang members and criminals should be locked away or put to death. To them, Kim offers an alternative.

“Is there anything good about this guy that could grow into something better?” asks Kim. “Is there room for redemption? For me, I like that part of it.”

___