Story by Susan Soon He Stanton.

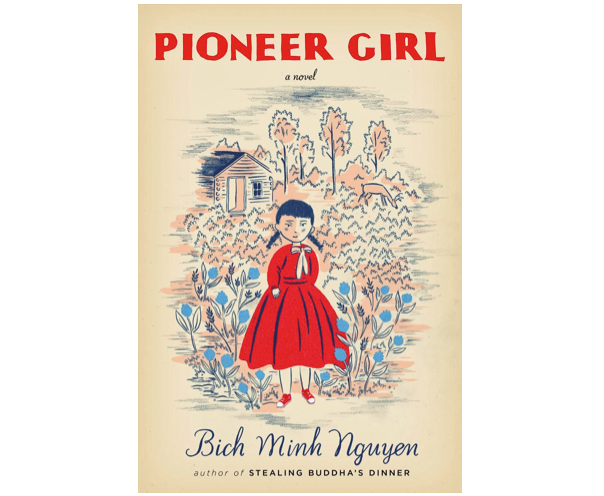

Engaging, humorous and unexpectedly suspenseful, Bich Minh Nguyen’s Pioneer Girl is the story of Lee Lien’s literary pilgrimage to uncover a mystery that connects Rose Wilder, the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, to Lee’s own family. Lee, the child of Vietnamese immigrants, grew up in the Midwest. Her perpetually dissatisfied widowed mother shuttles Lee, her brother Sam and her grandfather from town to town as they struggle to make a living running generic Asian-themed buffets catering to Americans. A gold pin that Lee’s grandfather received from a woman named Rose in Saigon causes Lee, a frustrated, out-of-work scholar, to speculate that the pin originally belonged to Laura Ingalls Wilder. Lee abandons her mother and their restaurant to embark on a cross-country adventure, discovering secrets hidden within Rose Wilder’s papers. Reappropriating the American classic Little House on the Prairie series to echo Lee’s transient upbringing in the heartland, Nguyen’s striking prose spins a multi-generational tale that investigates the narrative we use to create our family histories. Nguyen speaks with Audrey Magazine about her latest novel.

[wp_ad_camp_1]

Q: Can you talk about your inspiration for intersecting the life of a young Vietnamese American woman with the Little House on the Prairie saga?

Bich Minh Nguyen: As a child, I strongly identified with Laura Ingalls Wilder. Her family was always looking for a home, a right home, where they wanted to be. In the back of my mind, it resonated with me as an immigrant story. I came to America in 1975, and I think what my family went through in resettling paralleled the Little House on the Prairie books I was reading.

I wanted to create a link between Lee’s family and the Ingalls. Both the Ingalls and the Liens are constantly moving. A phrase used in the Little House books is “itchy wandering foot.” The pioneer spirit is the belief that there’s got to be something better if we just keep moving – we just need to find out what’s beyond those hills, what’s beyond the visible horizon – and that feeling can be intoxicating.

Q: Lee is discriminated against for being an Asian American Wharton scholar. She’s constantly pushed towards ethnic lit. Is that something you’ve come up against while writing this book?

BMN: It can be difficult for writers of color to write about people who are not of their own background, without facing some kind of criticism. There’s a belief held by many people that if you are a person of color, you should only be writing about your own experience. When I began, many people were puzzled why an Asian American would be interested in writing a story involving Little House on the Prairie. The notion was that these books are so iconically American, why would an Asian American be interested? I wanted to question that questioning, to create a narrative of the Rose Wilder stories with the story of the protagonist, Lee.

Q: Lee makes some pretty juicy discoveries about Rose Wilder’s personal life. How much of it is true?

BMN: I took a ton of liberties. However, I did spend a lot of time reading Rose’s journals at the archives. But Lee’s theft of archival materials is made up. It’s not something that I would do myself, but I love imagining it. The Rose Wilder Lane papers in Iowa are cataloged in a fairly messy way. I was surprised there were so many souvenirs and trinkets jumbled together, and the thought crossed my mind, “Boy, you could just take one of these things.” Every once in a while a scholar will find a treasure trove of lost letters. I’ve always loved this idea. You’re an ordinary scholar, and you make an accidental and incredible discovery.

In Rose’s papers, I did find a photograph of a Vietnamese man that she took while in Saigon. The photo struck a chord. I thought, maybe she really did develop friendships there. It was the first connection I could make between something having to do with Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Vietnamese American experience.

[wp_ad_camp_2]

Q: Your descriptions of the pseudo-Asian buffets in small Midwestern towns are appalling and fascinating. Did you have a lot of experience eating at those buffets growing up?

BMN: I did. And for research purposes, I had to go back. I went to the worst ones, the most grimy and rundown. For years it fascinated me that these restaurants are in the middle of nowhere but are somehow surviving and run by Asian people. They serve corn syrupy fast food. It’s really American food more than Asian.

Q: Lee’s brother, Sam, chooses to move to San Francisco to be around other Asians. You grew up in the Midwest, but you have recently moved to San Francisco. Can you speak more about your motivation to relocate Sam?

BMN: When I wrote Pioneer Girl, I was living in the Midwest. I had no idea that I would ever move to the Bay Area. Part of the Midwestern experience for me is conflicted. When I was growing up there, I always thought, this is where we are, this is our home. However, there’s a longing to see what the coasts are like because all you ever hear is that life is on the coasts, in California or New York, and the middle is just fly-over country. I wanted there to be a character who not only felt that way but did something about it. But it’s not a positive thing Sam does; it’s a selfish thing, and that’s what happens to a lot of Midwesterners who leave. It can feel like you are abandoning something. I wanted to get at that feeling.

Details Hardcover, $26.95, bichminhnguyen.com.

[wp_ad_camp_3]

This story was originally published in our Spring 2014 issue. Get your copy here.