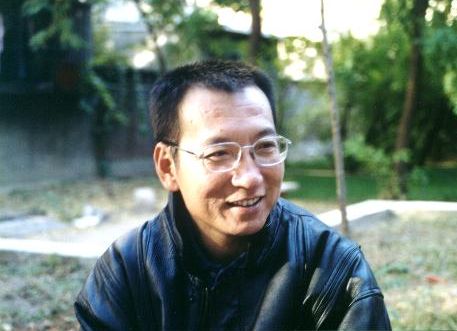

BEIJING — Friends of the dissident who would become China’s first Nobel Peace Prize laureate had for decades urged him to leave the country that sent him to prison time and again. Liu Xiaobo always said no.

When Liu had a chance to seek asylum abroad after the 1989 Tiananmen pro-democracy protests, he declined. Urged again in the 2000s to leave after needling the government with his essays, he again said no. He might be safer overseas, Liu told friends, but he would sacrifice the moral authority of a campaigner who persisted under one-party authoritarian Communist rule.

Then in March, one development finally broke the resolve of China’s most famous political prisoner: his wife’s declining health.

“For the person he loved, he changed his mind,” said Wu Yangwei, a close family friend who writes under the name Ye Du.

Forcibly sequestered in her home by state security agents for seven years because of her husband’s alleged crimes, Liu Xia had become severely depressed and was suffering heart attacks. Once Liu, serving an 11-year prison sentence, found out about her condition, he decided he would be willing to leave if it would save the soft-spoken poet and artist, friends said.

But following Liu Xiaobo’s death Thursday after a brief battle with advanced liver cancer, friends and supporters are now concerned that Liu Xia may never regain her freedom. Foreign officials including the U.S. ambassador to China, European Council leaders and others have called on Beijing to release Liu Xia, who was never convicted of any crimes.

Back in March, before his cancer diagnosis, Liu Xiaobo’s change of heart prompted a round of talks between Chinese authorities and the German government in an effort to get Liu Xia out of China, possibly to Germany, for treatment of a heart problem, said Liao Yiwu, a close family friend and Berlin-based writer.

“We were encouraged by the negotiations’ progress,” Liao said. “But then Liu Xiaobo’s situation exploded suddenly in June.” Liao said he and the couple thought they could argue that some cancer treatments could only be performed in Germany. The German Embassy in Beijing declined to comment.

Beijing rejected the Lius’ requests and the appeals from foreign governments, saying Liu Xiaobo was receiving the best possible care in China. Friends now fear Beijing may restrict Liu Xia’s movements and prevent her from communicating with the outside.

“Liu Xiaobo surely shared with her his thoughts, which can be expressed through Liu Xia,” said Wu, the writer. “Imagine the consequences if Liu Xia should be free and accept the Nobel Peace Prize on his behalf?”

After Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2010, Beijing placed tight controls over Liu Xia, banning her from using a cellphone or the internet, effectively cutting her off from the outside world. After she was diagnosed with depression, she was allowed to visit with a small number of friends. Guards remained outside her door 24 hours a day, sleeping on a cot at night.

“This kind of isolation is (a form of) torture, and it’s been seven years for her,” said Yu Jie, a family friend who has written a biography of Liu Xiaobo.

Born in 1961 into the family of a senior financial sector official in Beijing, Liu Xia quit her post at a publishing house in her 20s and pursued poetry and painting instead of the tax bureau job that her father arranged for her.

By the time they met, Liu Xiaobo had gained considerable notoriety for his bold criticisms of heavyweight authors. During the 1980s, a period of relative freedom and intellectual foment in China, he gave popular talks at Beijing Normal University and traveled to New York and Norway to lecture.

In later years, Liu Xia, an accomplished poet, would bristle at the suggestion she was subordinate to Liu Xiaobo. But on Tiananmen Square in the heady early months of 1989, she gazed from afar on the charismatic literature professor — her future husband — who was organizing a hunger strike days before the tanks rolled in.

“I didn’t have a chance/to say a word before you became a character in the news/ everyone looking up to you as I was worn down/ at the edge of the crowd,” she wrote.

Liu Xiaobo’s first marriage dissolved after his arrest and first stint in prison for his role in the Tiananmen protests. He and Liu Xia became close and fell in love after he was freed in 1991. He told his friends he was captivated by her free-spirited, singular beauty. She told prison authorities who tried to persuade her not to marry Liu that she would only marry one man: “that enemy of the state.”

They wed in 1996, after Mo Shaoping, Liu Xiaobo’s lawyer and long-time friend, convinced prison officials to allow the marriage in the labor camp where Liu was spending one of his four terms in detention.

During Liu Xiaobo’s three-year stint, Liu Xia made the train ride 36 times — once a month — to visit her husband. A poem she wrote during the 10-hour trip says: “The train heading for the concentration camp / Sobbingly ran over my body / But I could not hold your hand.”

In the years between 1999 and 2008 when he was free and continued to write prolifically, Liu Xiaobo told friends he saved what money he earned so Liu Xia could survive in case something happened to him. The times when he did splurge, Mo said, he bought her bottles of expensive red wine.

Then in 2009, Liu Xiaobo was convicted of inciting subversion of state power after he co-authored Charter 08, a document calling for the end of one-party rule. In a final statement that he prepared to give in court but was never allowed to deliver, he paid a loving tribute to Liu Xia.

“Your love is the sunlight that leaps over high walls and penetrates the iron bars of my prison window, stroking every inch of my skin, warming every cell of my body,” he said in his statement, which was read a year later at the Nobel ceremony in Oslo.

That year was when Liu Xia’s isolation began. In a rare interview, she told The Associated Press in 2010 that she did not believe she would be kept in captivity forever.

But the pressure never eased.

In 2014, Liu Xia was hospitalized for a heart attack. Friends said that when she visited Liu Xiaobo in prison she was forbidden from discussing her health or house arrest on pain of losing her visitation rights.

During one visit, Liu Xiaobo suggested that Liu Xia could take a vacation to Europe if she felt bored. She laughed bitterly but said nothing, according to Yu, the biographer.

It was only this year that she brought up her health condition.

When Liu Xiaobo learned about his wife’s dire situation in March, “he changed his mind about staying in China,” said Wu Renhua, a close family friend. He “wanted to use the remainder of his life for Liu Xia’s freedom, but in the end that did not happen.”

By Gerry Shih and Didi Tang