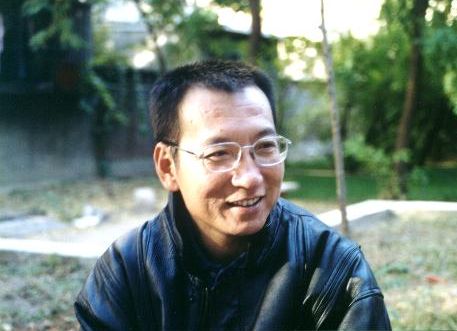

SHENYANG, China — Imprisoned for all the seven years since he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Liu Xiaobo never renounced the pursuit of human rights in China, insisting on living a life of “honesty, responsibility and dignity.” China’s most prominent political prisoner died Thursday of liver cancer at 61.

His death — at a hospital in the country’s northeast, where he’d been transferred after being diagnosed — triggered an outpouring of dismay among his friends and supporters, who lauded his courage and determination.

“There are only two words to describe how we feel right now: grief and fury,” family friend and activist Wu Yangwei, better known by his penname Ye Du, said by phone. “The only way we can grieve for Xiaobo and bring his soul some comfort is to work even harder to try to keep his influence alive.”

The 1989 pro-democracy protests centered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, by Liu’s account, were the “major turning point” of his life. Liu had been a visiting scholar at Columbia University in New York but returned early to China in May 1989 to join the movement that was sweeping the country and which the Communist Party regarded as a grave challenge to its authority.

When the government sent troops and tanks into Beijing to quash the protests on the night of June 3-4, Liu persuaded some students to leave the square rather than face down the army. The military crackdown killed hundreds, possibly thousands, of people and heralded a more repressive era.

Liu became one of hundreds of Chinese imprisoned for crimes linked to the demonstrations. It was only the first of four imprisonments.

His final prison sentence was for co-authoring “Charter 08,” a document circulated in 2008 that called for more freedom of expression, human rights and an independent judiciary.

“What I demanded of myself was this: Whether as a person or as a writer, I would lead a life of honesty, responsibility, and dignity,” Liu wrote in “I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement,” which he was prevented from reading aloud in court at his sentencing in 2009. He was sent to prison for 11 years on charges of inciting subversion by advocating sweeping political reforms and greater human rights in China.

A year later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. The Norwegian committee lauded Liu’s “long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.”

The award enraged China’s government, which condemned it as a political farce. Within days, Liu’s wife, the artist and poet Liu Xia, was put under house arrest, despite not being convicted of any crime. China also punished Norway, even though its government has no say over the independent Nobel panel’s decisions. China suspended a bilateral trade deal and restricted imports of Norwegian salmon, and relations only resumed in 2017.

Dozens of Liu’s supporters were prevented from leaving the country to accept the award on his behalf. Instead, Liu’s absence at the prize-giving ceremony in Oslo, Norway, was marked by an empty chair. Another empty chair was for Liu Xia.

On Thursday, the Nobel Committee said Beijing bore a heavy responsibility for Liu’s death. But it also leveled harsh criticism at the “free world” for its “hesitant, belated reactions” to his serious illness and imprisonment.

“It is a sad and disturbing fact that the representatives of the free world, who themselves hold democracy and human rights in high regard, are less willing to stand up for those rights for the benefit of others,” said the organization’s chairwoman, Berit Reiss-Andersen.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel said Liu Xiaobo was a “courageous fighter for civil rights and freedom of opinion.” U.S. Senator John McCain lauded Liu as “a champion for human rights” whose death was “an egregious violation of fundamental human rights.” U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, meanwhile, urged Beijing to release Liu’s wife from house arrest and allow her to leave the country if she wishes.

Liu was born on Dec. 28, 1955, in the northeastern city of Changchun, the son of a language and literature professor who was a committed party member. The middle child in a family of five boys, he was among the first to attend Jilin University when college entrance examinations resumed following the chaotic 1966-76 Cultural Revolution.

After spending nearly two years in detention following the Tiananmen crackdown, Liu was detained for the second time in 1995 after drafting a plea for political reform. Later that year, he was detained a third time after co-drafting “Opinion on Some Major Issues Concerning our Country Today.” That resulted in a three-year sentence to a labor camp, during which time he married Liu Xia.

The couple’s friends and supporters described the dissident and his soft-spoken wife as being deeply in love. In the same statement Liu had prepared for his trial, he addressed his wife.

“Your love is the sunlight that leaps over high walls and penetrates the iron bars of my prison window, stroking every inch of my skin, warming every cell of my body, allowing me to always keep peace, openness, and brightness in my heart, and filling every minute of my time in prison with meaning,” he said.

“But my love is solid and sharp, capable of piercing through any obstacle. Even if I were crushed into powder, I would still use my ashes to embrace you.”

Yu Jie, a longtime friend and a biographer, said Liu frequently gathered a small group of friends for frequent dinners at his favorite local Sichuan hot-pot restaurant, where he regaled younger intellectuals on literature and philosophy before returning home to write until dawn, as was his habit.

“No one was as active as he was, and no one had so much social interaction with the young people,” Yu said. “He was a bridge for generations of thinkers.”

Liu was only the second Nobel Peace Prize winner to die in prison, a fact pointed to by human rights groups as an indication of the Chinese Communist Party’s increasingly hard line against its critics. The first, Carl von Ossietzky, died from tuberculosis in Germany in 1938 while serving a sentence for opposing Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime.

“Hitler was wild and strong and thought he was right — but history proved he was wrong in imprisoning a Nobel Peace Prize winner,” said Mo Shaoping, an old friend and Liu’s former lawyer. “The authorities consider Liu Xiaobo guilty, but history will prove he is not.”

By Christopher Bodeen, Gillian Wong, Han Guan Ng