By Shingyung Oh

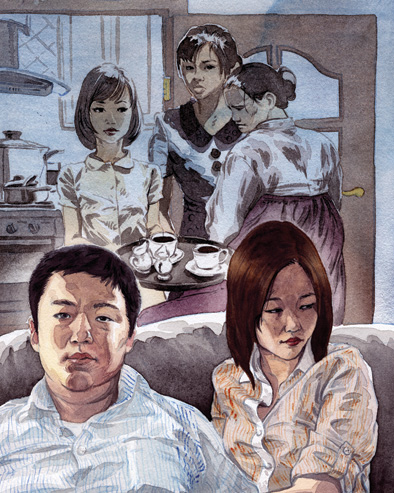

Illustration by Kyungduk Kim

About a month after my brother got married, I saw a side of my mother I had never seen before.

It started when my brother and his new wife visited our house after their honeymoon. While they were there, everything seemed fine. We hung out, had dinner with the requisite fruit and coffee afterwards, watched a little TV. Then my brother and his wife left with bags full of leftovers and other dishes my mother made especially for the newlyweds.

[ad#336]

But after they left, the grumbling started. Why did she sit on the couch all evening? Why didn’t she do the dishes? Why am I serving her? Why can’t she get her own cream and sugar? Who does she think she is, a guest? Is she going to keep coming over expecting to be served?

Whoa. What happened to my usually reasonable and generous mother?

As I recall the evening, Mom gave no indication that she wanted my sister-in-law (let’s call her Ann) to help. If anything, Ann barely had a chance to pitch in since my sister and I, our mother’s lifelong sous-chefs, flanked my mother pretty much the entire time. Ann did seem to hover a bit initially, as if she wanted to help, but my guess is that she wasn’t sure how to do so and wasn’t very comfortable in the kitchen in the first place. The three Oh women did nothing to draw her into our cooking circle. If anything, we bumped and shooed her out of our way.

I listened to my mom complain and then asked her why she didn’t ask Ann to help. She responded, “I shouldn’t have to ask.”

Hmm. That didn’t sound very reasonable to me. I explained to my mother that asking Ann to help would be more merciful than waiting for her to figure out how to inject herself into the chaos of our kitchen. And perhaps Ann and my mom had different notions of what was expected of a daughter-in-law, especially since we now live in the United States.

Ever so hesitantly, Mom asked, “Really, you think I should say something?” I reassured her that she should.

Unfortunately, their next visit was more or less the same. My mother did try to ask Ann to help out here and there. While Ann complied, she whisked herself away immediately after chopping her one carrot, showing that she really wasn’t into the spirit of the occasion. After a couple of tries, Mom gave up and stopped asking. Again this time, the couple left our house with bags full of leftovers.

[ad#336]

When the complaining started, I interrupted and said, “Mom, if you want her to help, you should just take charge and direct!”

She responded, “But she’s not my daughter. I can’t tell her what to do. Besides, how am I supposed to do my part if she doesn’t do hers?”

And then I understood. My mother, with her big heart, wanted to be a generous mother and mother-in-law. She went out of her way to prepare multiple dishes for my brother and his new wife, not just for this one meal, but for several meals to come. In the framework of the traditional Korean hierarchy, where mothers are relegated to the role of a household cook, my mom wanted it to be clear — for all to see — that she wasn’t doing it because she had to, but because she wanted to.

And she needed Ann’s help to do that. She wanted Ann to make clear that she understood that my mother was not serving her. How helpful Ann was in the kitchen was beside the point. It was a matter of signaling an acceptance of my mother’s social status, which in turn allowed my mom the space to be generous. As my mother saw it, Ann was failing to do her part in this delicate dance, the one dance my mother believed was theirs to assume.

For the next few years, I watched my mother struggle with her part, veering between trying tentatively to live up to the role of the dominant Korean mother-in-law she often saw played out on Korean dramas and then reverting to her role of playing the magnanimous mother-in-law, only to rebuke herself for being overly generous whenever she felt slighted. She often called to solicit my input on how she should handle this or that situation as she struggled to interpret her social role in our American context. She often ended our calls by resolving, “I’m going to try to be a better mother-in-law from now on.”

I began to see just how short the end of the stick is for Korean women of my mom’s generation. How suppressed their social power must be that it finds its clearest expression in the kitchen, that the trivialities of preparing a meal can dictate the course of their lifelong relationships with other women. I am reminded of the stories I read of the many wives of Fundamentalist Mormons who fight over the pecking order in using the laundry machine.

[ad#336]

Whenever I hear complaints about mean Korean mothers-in-law, I feel a little pained. I know how extreme some Korean mothers can be because I’ve met quite a few of those (like my high school friend’s mom who demanded to know our SAT scores and grades every time we visited), but I would hate for our moms to be buried under yet another stereotype. I wish I could help Korean mothers- and daughters-in-law understand the social and cultural context of what the other is trying to communicate, what often isn’t reduced to words. I want to explain why identifying cultural differences on a superficial level isn’t the same as understanding the depth and power of such beliefs and values.

After all, who knows when it will be my turn to take up this dance, and I’ll be looking for someone to help me find my rhythm to this evolving beat.

Shinyung Oh is an attorney and writer based in San Francisco. visit her blog atwww.shinyungoh.blogspot.com.