Speak Now: A space for reflections on Sa-i-gu

Over the years, KoreAm has documented the impact of the 1992 Los Angeles riots on ours and other communities, and urged an understanding of lessons learned. As we count down to the 20th anniversary next year, charactermedia.com will be running a riot article, image or testimonial in this space every week until April 29, 2012. Some will be taken from our pages, while others will be excavated from our own personal archives. We welcome your submissions—first-person memories (no word limit), pictures, poems and (photographed/scanned) artifacts—for this project, too. Please email them to riots@charactermedia.com. Many of us were mere children in 1992, but 19 years later, we have voices. We can speak now.

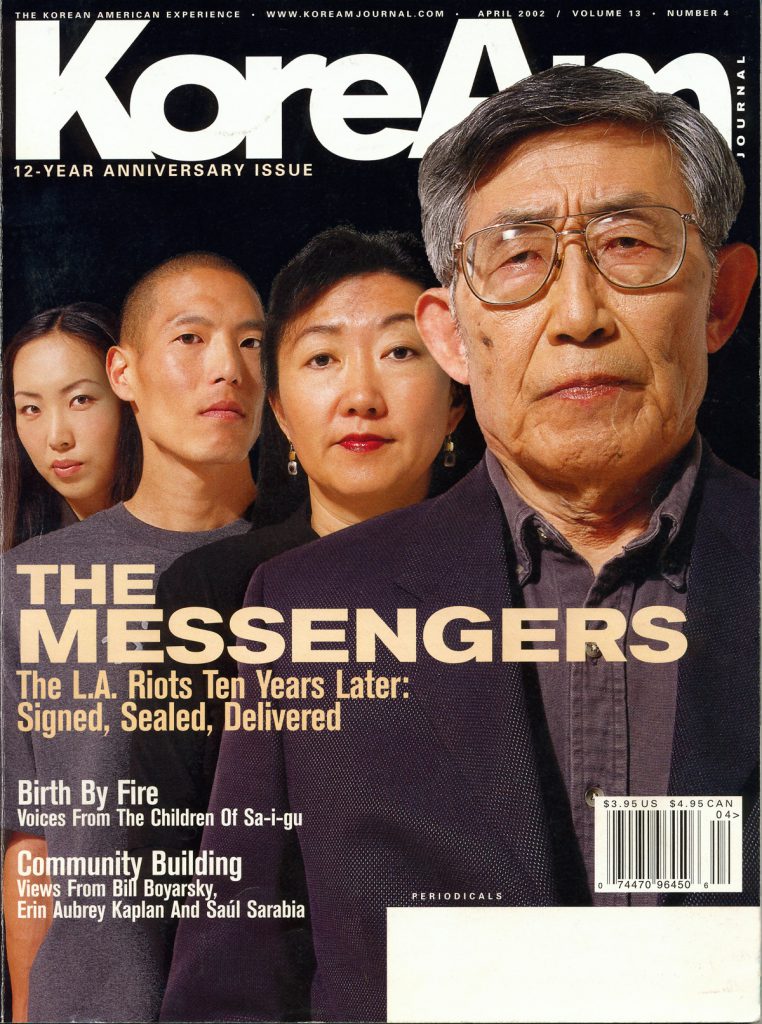

The following piece was first published in the April 2002 issue of KoreAm Journal.

Born on the 29th of April

> By Angela E. Oh

I have tried to write this article at least six times.

What is there to say a decade after the eruption of Los Angeles in the spring of 1992? People want to know if things have improved for Korean immigrants living in the Southland. They want to know whether the black/Korean conflict has been overcome. The questions from within the Korean community are: “Why our parents? Why us?”

There are no real answers to these questions. Race relations continue to be complicated, filled with tension because the change that is taking place does not come easily for any of us. Blacks and Koreans, in particular, have made no major advancements in relation to one another. A few shining examples — but certainly no depth of understanding has been cultivated. Korean immigrants struggle still. There are no indications that things have improved greatly or declined to any significant degree. In 1993, the number of immigrants entering the United States declined; then in 1994 and since then, the numbers have started to rise again. The trans-Pacific reality of our 21st-century immigrant existence is clear. Korean American youth vaguely recall what happened in 1992.

The question of “why” cannot be answered in a single article. This answer is in the stories of families, the stories in the community, and the stories told in hundreds of books, research papers, films and expressions of art.

A decade later, there are forums, town hall meetings, films, art exhibits and a memorial at a Koreatown park. It is important to remember what happened. It is important to feel the present effects of those five days of burning, looting and vandalism. And it is important to recognize that we cannot really know, from ten years into the future, what the confusion, anger and suffering really meant to the lives of more than 2,000 families in the Korean American community of Los Angeles. To what end, their unwitting sacrifice?

I am looking through three files: “Korean Killings – 1993,” “AEO Personal,” and “AEO Miscellaneous.” Out of the pages of the “Korean Killings” file I see that between Feb. 5, 1992, and April 29, 1993, there were 17 reported incidents of violent crime targeting Korean-owned small businesses in Los Angeles. In that same time period, there were incidents of violence against Koreans in Chicago, Portland, Atlanta and Philadelphia — some deaths and some serious injuries. These attacks were not reported in the English-language press. They were covered only in Korean-language newspapers. The reality for Korean immigrants shortly after the acquittals in the case against the police officers who beat Mr. Rodney G. King was a nightmare. But no one really cared.

Out of the “AEO Personal” file I find many notes and letters, including a two-page, single-spaced letter from a Mr. Goldfarb, who refers to me as “deceptively congenial.” He goes on to write: “Under it all there are the makings of a skillful wannabee [sic] liberal political, with perhaps her own ambitions. Of course, she has a right. But from previous appearances of hers, and her appearance on your show tonight, I am more convinced than ever that she has an agenda analogous to the poverty pimps (decayed black civil right “leaders” in the mold of a Jesse Jackson, Mark Ridley Thomas, … and Danny Bakewell).” And so on, and so on.

Then, I find the letter from the Southern California Korean College Students Association, setting forth their “DEMANDS,” including:1) the resignation of then-police Chief Daryl Gates for “dereliction of duty”; 2) an apology from the media for inaccurate coverage of the Riots; 3) reparations for all the people — both Korean American and African American — who suffered due to the “incompetence and ineffectiveness” of the police chief and other government officials; 4) an apology from the mayor for failing to have clear communications with the police department; and 5) a demand for an immediate end to police brutality against people of color and a promise from the justice system to protect the civil rights of all people. The students claimed at that time to represent 20,000 Korean American students from 20 campuses. They were inspiring.

As I search through the papers, I see there were so many worthwhile efforts to express a way to heal racial conflict — one using the Korean mask dance (talchom) to portray the conflict and resolution through storytelling. The Multicultural Bar Alliance and the Southern California Civil Rights Coalition called for help in monitoring the prosecutions of some 10,000 people arrested for various misdemeanors during that period. Many lawyers volunteered their time and talent to help.

These files are a small part of the letters, memos, reports and other materials that were gathered by me in the aftermath of 4-29. Though they are pieces of paper tied to the past, they are also powerful reminders of what we carry with us as part of our lives in the present. It is impossible to describe clearly what happened in 1992 in Los Angeles. You had to live here and feel the heat, the confusion, the sadness and the anger — all of which was mixed with the disappointment stemming from the fact that the humanity among us was lost for four or five days.

Some ask, “How did the Riots affect you personally?” My response is: It destroyed my personal identity and privacy, it ruined my plans to pursue a career in law, and it caused my life to take unplanned detours — many of which have been difficult, scary, painful and transforming. I have learned that all of the questions about race relations, economic opportunity, justice, respect for others and political empowerment have less to do with needing a voice and vision and much more to do with needing quiet and a genuine opportunity to reflect. I am blessed to have the family and friends who make my life so rich. I embrace the surprises that life brings — both the good ones and the bad. Each year, when April 29 rolls around — whether there are town hall meetings or memorials — I remember the thousands of Korean American families that were affected by the riots, and I repeat, Korean America was born on April 29, 1992.