My Decision

It is estimated that one in three American women will have an abortion in their lifetimes. Yet we rarely hear of Korean American women telling their stories. One writer shares hers.

by Yong Hee Eo

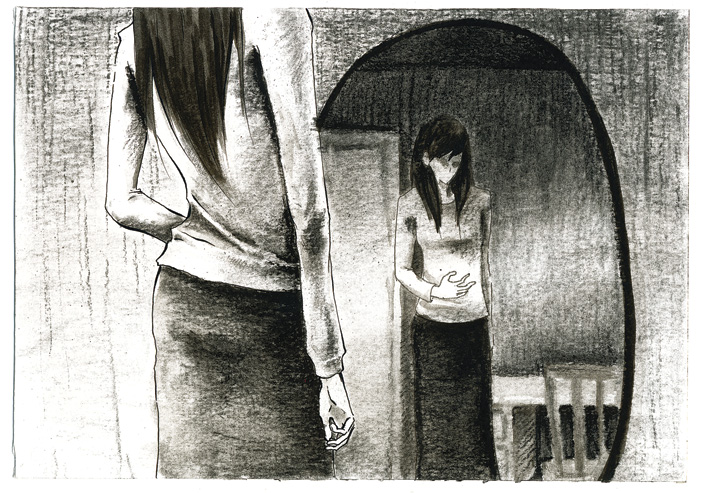

illustration by Ann Lee

MY STORY BEGINS WITH a relationship I had with a young Korean American man that started when I was 19 years old. I first noticed him in a class we had together. He walked into the room with an easygoing confidence that matched his athletic build and 6-foot tall frame. He had light brown eyes that became animated whenever he spoke, and they gave my stomach butterflies when I looked into them. We soon started dating.

Things moved quickly. He met my family, and they loved him. He came from a blue-collar background, where he had learned the value of hard work and family. He worked at his parents’ dry cleaners every weekend, and he helped my uncles move my mother into her house. He drank soju with us at our family gatherings and patiently listened to their drunken advice on life.

He was close to his mother, and I soon learned why. She, along with her children, suffered physical abuse at the hands of his alcoholic father. I didn’t think this would affect our relationship, until, little by little, I started to see the same behavior come out of him. His dysfunctional home life was too powerful for him to overcome. “You think this is bad?” he would ask me after particularly bad episodes. “This is nothing compared to what my mom has to go through.” I said nothing.

His love letters read like apologies for loving me too much, and at the time, I believed him. This attitude seemed common in Korean culture; when my uncle found out about the nature of our relationship, he explained that it was because my boyfriend loved me so much that he could not stand other people to have me. But when I finally told my parents about our relationship, my father’s head fell in disappointment, and my mother asked me why I let a man treat me that way. In my parents’ eyes, domestic violence was something I could control, and when I couldn’t, I became tarnished.

Almost a year into our relationship, I caught a knee-buckling flu where even fresh air made me want to throw up. The doctor prescribed a cocktail of pharmaceuticals to alleviate my symptoms, and to my surprise, administered a pregnancy test. “Just in case,” I remember him saying.

When the test came back positive, the doctor ordered me to discontinue my medication. I burst in through the door when I got home and fell onto my bed, letting out a cry so guttural that I barely recognized myself. My boyfriend was in the room, and I gasped out what the doctor’s office had told me.

Impulsively, the baby’s father proposed that we get married. For a moment, I pictured our life together.

The pregnancy would shatter my family. My parents would cut me off socially and financially. I would drop out of college to care for our child, stalling the education that my family valued above all else.

The abuse from the baby’s father, both physical and emotional, would only escalate with the added stress of caring for another human being. I would be brought into his family where the patriarch was his father, a man whose violent and irresponsible actions were being replicated by his son.

But still I fantasized, despite the contempt my parents would have towards me, of the joy my child would bring into their lives. I looked back on my childhood and remembered the comfort I felt when I clutched my father’s hand. I felt guilty that I was about to rob my child of these future memories.

The baby’s father looked at me with wide eyes, and I said no. I decided I could not have a child, then or with him. I did not want to raise a child in a household where he or she would learn that our family’s notion of love includes violence. I could not raise this child by myself, nor did I want to raise this child without the presence and protection of my family. To his credit, he allowed me to make the choice on my own.

We woke up early on the day of the procedure. The clinic grouped the women together in a warm waiting room with IV needles for the anesthesia coming out of our arms, and they called us to the surgery room one by one. Although the drugs relaxed me during the procedure, I remember holding back tears when a drop of blood slowly trickled down my backside.

After the anesthesia wore off, I felt a wave of relief, and then guilt for feeling relieved. I slowly walked into the outpatient room, where my boyfriend was waiting. I couldn’t look at him during the drive home.

I fell asleep when I got home and, when I woke up, he had left. I saw him again at 4 o’clock in the morning, when he came over drunk and promised never to leave my side.

I stayed with him for another six months after the abortion, despite realizing that I did not want children with him. A part of me could not see a better future after my decision—I felt undesirable, tainted and less-than-worthy of other men. To a certain degree, I still do.

I didn’t leave the relationship until he became physical with me in public, in front of his friends. Instead of intervening, they looked down and did nothing. Later that night, he and I asked ourselves what we were holding onto, and the question answered itself: We were holding onto our child who would never be, and we needed to let go in order to move on from our destructive union. We broke up, and I cut off all ties to him and our mutual friends. Despite this, I still feel an unwanted connection to him that keeps him in my conscience, and he will be there for the rest of my life.

I finished school and threw myself into my career. I was only 20 years old when I became pregnant, and at the time, I was not ready to sacrifice my potential. I promised myself that if I made this choice, I would renew my sense of ambition and create a life for myself worthy of this decision.

It’s been five years. Now, I work in the California state Capitol on public policy affecting millions of people, and I volunteer my time to help elevate the political profile of the Asian Pacific Islander American community. I do my job every day not only for the public and my community, but also with the promise I made in mind.

I’ve sifted through articles, videos, documentaries and books to seek comfort in other women’s stories and to validate my inner turmoil. We see more and more women sharing their stories of late. Congresswoman Jackie Speier shared her abortion story last February on the House floor during a debate to end funding for Planned Parenthood. And MTV, in part due to the popularity of shows like 16 and Pregnant and Teen Mom, aired a documentary called No Easy Decision, about a young, financially struggling couple’s decision to terminate a pregnancy. I admire the courage it takes to share one’s abortion story and talk about the grief, helplessness and strength that women experience.

In the stories written by these brave women, however, the Korean American voice was glaringly absent. But when I privately shared my story with my Korean American girlfriends, some of the reactions I received were silence, and then, in a quiet voice, “I had one, too.” Sadly, these stories largely go untold, and we Korean Americans are left to silently navigate the aftermath of our choice. I constantly second-guessed both my guilt and my relief, and the shortage of stories from the Korean American perspective amplified the uncertainty. By sharing my story publicly, I hope that at least one person who is experiencing what I experienced will read this and find some solace and peace. To her, I say: You are not the first Korean American to have an abortion; you will not be the last; and most importantly, you are not alone.

This article was published in the September 2011 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today!

[ad#bottomad]