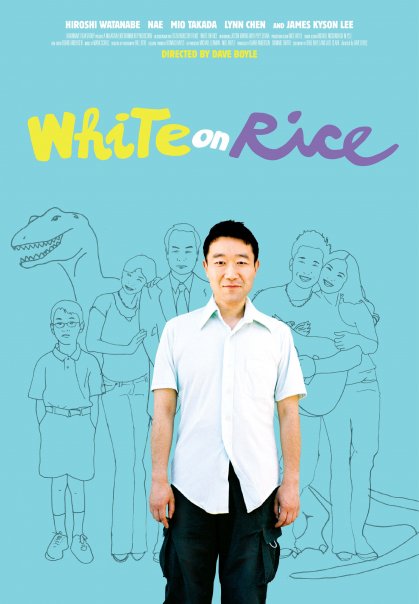

I really, really wanted to like White on Rice.

I wanted to like it because it’s an indie. I wanted to like it for the controversial pot it stirred before anyone had seen it. I wanted to like it because the trailer was funny and smart. I especially wanted to like it for its all-Asian cast of characters in a comedy. A comedy. There were no kung fu assassins, badass dragon ladies in leather, traditional robe-wearing parents hiding ancient laundry secrets, or hyper-American-born immigrant offspring who spit Bubblicious on the ancestors and cuss in two languages.

But I left the theater with the same uneasiness I feel when I see a white person pour soy sauce all over a perfectly steamed bowl of jasmine rice.

Listening to and reading interviews with Dave Boyle, the creator of White on Rice, I wondered where the movie he talks about is playing because I really want to see it. It isn’t the one I saw.

According to Boyle, he originally wrote the script based on some autobiographical elements of his own life when he was in a questioning period, worried about whether or not he would amount to anything in life, or if he would forever be a loser living in his sister’s basement, completely dependent upon others for survival.

Oddly, none of that comedic angst translated into his Japanese American flavoring of the film when he decided to write Hiroshi Watanabe as the lead. Any edginess that existed in the original script became coated in syrupy cutesiness.

What Boyle ended up with was a cast of quirk-filled characters, Watanabe’s goofy mug and predictable sight gags that were amusing but cumulatively did not move the story—or characters—forward.

Unfortunately, that means viewers never get to see the complete skills of Watanabe, James Kyson Lee or Lynn Chen. At least Mio Takada is a scene-stealer as “Tak,” the most rounded character of the film.

I’m all for writing characters that are human first and their ethnicity is another dimension of who they are rather than the singular definition. However, creating vanilla characters without any real depth is not much of an improvement to the standard stereotypes.

Boyle knows that the best comedy writing has its foundations in real pain. What changed when he decided it was an Asian American story? Does he think we all cope with a Hello Kitty view of the world?

We can be edgy. Damn it.

While I don’t believe that artists should be relegated only to material that they know firsthand, they do have an obligation to be as authentic as they can—no matter what kind of wacky world they create.

Boyle made such a deliberate effort to cast Asian actors (and to let everyone know he was doing so). I wonder why he didn’t tap a talented Asian American co-writer to work with him on the screenplay.