FOR much of his life, Nathan Nowack defined his nuclear family as a clan of four. As a 5-month-old, he was adopted from Korea by Caroline and Gerhard Nowack, a Caucasian couple in Oklahoma already raising a 3-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Amy, also a Korean adoptee.

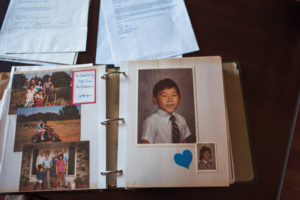

He enjoyed a childhood brimming with love, outdoor adventure and the freedom to be himself, as pictures from his family albums attest: infant Nathan cradled in the arms of his beaming mom as she holds him for the first time at the Tulsa International Airport, with his smiling big sis looking on; daredevil Nathan dressed in a “Rambo” outfit complete with sunglasses and weaponry; silly Nathan with his body buried under wet sand while on family vacation in Hawaii; and proud Nathan standing with pals in front of a homemade fort built into a tree.

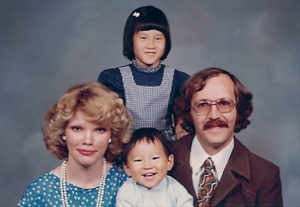

Certainly, the mere sight of this blond artist mother, curly-haired chemist father and their Asian children would attract the stares of many in their small town of 35,000, but as multiple portraits taken over the years would capture, this was their family: close-knit and happy.

And yet as beautiful as this family picture was and has always been to Nathan, now 38 and a wedding and portrait photographer living in Southern California, a part of it never got colored in. Why was I given up for adoption? Where are my birth parents? These questions would sometimes creep into Nathan’s mind, even when he was very young.

“It’s not that he was preoccupied with Korea or where he had come from biologically, but [Nathan] did reference that from time to time,” recalled Caroline Nowack, speaking by phone from Colorado, where she and her husband now live. “[Around age 7 or 8], he used his allowance to buy a Korean flag. And, once, when he was quite young, as I was putting him to bed, he said, ‘I wonder where my other mother is.’ It came out of nowhere. He didn’t really seem concerned about it, but it was there.”

Nathan’s adoptive parents always told their children—who are not biologically related—that, if they ever wanted to look for their respective birth families, they would support them. But, over the years, even as ever-curious friends asked Nathan why he hadn’t yet looked, he would tell them he didn’t feel the need to probe. He didn’t have any “emotional holes” to fill.

“I have a wonderful family,” he would reply. “I’m not looking for anything additional.”

Then one evening last spring, he saw a picture that unlocked a door he was prepared to keep closed for the rest of his life.

NATHAN and his wife of four years, Allison, were attending the Los Angeles premiere of aka DAN, a documentary telling the story of Korean American adoptee Dan Matthews, an L.A.-based rapper whose birth search startlingly revealed the existence of a twin brother. Matthews, raised by a loving Caucasian couple in California, would have an emotional reunion with his twin, along with his birth parents and his younger biological sister during a trip to Korea.

The story deeply moved Nathan. He saw the parallels to his own life. When a photograph of a 7-year-old Matthews with his adopted older sister from Korea, along with their Caucasian mother and father, flashed across the screen, it particularly resonated. It was one of those old-fashioned family portraits, with each member of the family forming one point in a diamond shape. Nathan knew that picture: he had one just like it.

“It’s two Caucasian parents and then two adopted Korean kids in the middle—it’s that photo from my childhood that I love. It’s that awkward family photo,” he said, laughing at the memory, while seated in the dining room of his Redondo Beach condominium. It’s one that Nathan proudly displays on his photography business’ website. “That photo is, for me, iconic,” he said.

Matthews’ near-identical family photo spoke to Nathan in a way nothing else had before. It seemed to say: This is you. You, too, can find your birth parents, possibly a sibling.

After the aka DAN screening, Nathan began connecting with other Korean American adoptees in Los Angeles. He also started researching adoption, learning that some 110,000 children were adopted from South Korea between 1970 and 1989. He learned that his own adoption in 1976 occurred through the Korea-based Eastern Child Welfare Society, which worked to place children through its U.S.-based affiliate, Dillon International, which happened to open an office in Oklahoma. That’s how Caroline and Gerhard, who yearned to provide a loving home for children who didn’t have one, came to think about adopting from South Korea. Their daughter Amy was among the first children placed through Dillon International.

Though Amy has never searched for her biological family because she said the details are “sketchy”—she was abandoned outside an orphanage—she encouraged her little brother, “Go for it. Mom and Dad always said, if either of us wanted to look into that, because it’s a part of who we are as human beings, they would help us or support us in any way possible.”

So, after 38 years, a thought-provoking documentary, the support of his adoptive family and a nudge from his wife—who also encouraged him to try to learn more about his family medical history—Nathan embarked on a birth search last summer. He didn’t have high expectations: The adoption agency warned that only 10 percent of adoptee searches yield any information that leads to a connection to the birth family. Nathan turned out to belong to that small percentile. Just a month after filing his final paperwork, he received a life-changing phone call.

Fast forward to March, more than six months after that call. Nathan’s expression still turns to disbelief when he remembers that moment. “I never would have expected I was the youngest of seven,” he said. “Like, wow, what?”

NATHAN was at the vet’s office getting pet food for his cat, when a Dillon International representative called him on his cell phone. In an excited voice, she began by telling him that, after the agency sent his birth search letter to the last known location of his biological parents, someone instantly responded. It was his older brother. “It was kind of crazy, I felt like the aka DAN story was happening to me,” recalled Nathan. “I was really excited at that point to know I had a brother.”

But, there was more. The agency representative told him that he also had five older sisters, and that his siblings had known about him his entire life. His oldest sister gave birth to a child within 10 days of Nathan’s birth in 1976, so whenever they celebrated the nephew’s birthday, they would think of their youngest sibling.

“This hit me pretty hard,” said Nathan. “It wasn’t just knowing I had a family, but that they all knew about me and wondered where I was. A little bit of the mystery from my past not only had names and ages, it had feelings and thoughts towards me.”

Yet the discovery about his birth family also proved bittersweet: Nathan learned that both his birth parents were now deceased. His father had died of stomach cancer in 1999, and his mother of gall bladder cancer in 2011, just three years before he began his birth search.

“I had just missed her,” Nathan said, wistfully, as he cast his eyes downward.

Later that same day, at home, Nathan opened an email from the agency that contained a photo from 1998, showing his older brother, Lee Jeong-hoo, now 49, when he was slightly younger than Nathan is now.

Staring back at Nathan from his 27-inch iMac screen was a man with the same eyes, arched eyebrows, tanned face, high cheekbones and ears that noticeably protrude out from the sides of his head. Even the spiked haircut was the same.

“Wow, he looks just like me,” a stunned Nathan remembered thinking of the photo. “I’ve never seen anyone who looks like me.”

For a photographer who has long had a fascination with doppelgangers and the magic of genetics, the moment felt surreal. One of Nathan’s unofficial hobbies is finding pictures of celebrities or random people who resemble his friends and then sending the latter a side-by-side comparison. But, in all these years of searching for look-alikes, Nathan never found any images of people resembling himself—until now.

A subsequent email sent by the agency included a picture of all of his siblings at a sister’s wedding. By now, Nathan was learning a little bit more about each of them. They ranged in age from 45 to 63 and had families of their own. He learned that his brother works at Korean Air and that one of his sisters runs a bibimbap restaurant.

The revelations proved overwhelming for Nathan. His adoptive family, admittedly a little worried that his search would yield no news or hurtful news, was also taken aback with a mix of shock and delight.

“I think it’s just incredibly exciting,” said Gerhard. “If there were just one sibling or just his parents … but to have this enormous family? That’s gotta be exciting and also a little intimidating in a way.”

Caroline said she felt as if her own family had just “increased in size.”

Within just a couple of months, this surreal experience for Nathan would feel a bit more real: Lee Kyoung-mi, the youngest sister who works for Herbalife in Korea, announced that she and her husband were planning a trip to L.A. in March to attend a company convention.

Nathan was about to meet his first blood relative.

IN THE LOBBY of the JW Marriott hotel in downtown L.A. the afternoon of March 7, Nathan and Allison stood near the front desk scanning the crowds of people. It was going to be difficult to pick out Kyoungmi among the sea of Asian faces, they thought.

Then Nathan felt a tap on his shoulder.

“Sang-kil?” a voice said, calling him by his Korean name.

Still virtual strangers to each other, the smiling siblings shook hands and introduced their respective spouses. Kyoung-mi’s bilingual friend provided much-needed Korean-English translation as the group sat down at the nearby hotel bar and talked over coffee and juice.

“She kept on staring at Nathan,” Allison said of Kyoung-mi. “She said,‘I keep on seeing my older brother, but when he was younger.’”

“‘But more handsome and with better skin,’” added Nathan in a feigned soft female voice, mimicking his sister. Information about family, jobs and even hobbies were exchanged in just two hours. The siblings, who also bear a strong resemblance to each other, discovered their shared passion for competitive table tennis, an unexpected, “kind of a cool” link, said Nathan.

The conversation eventually turned to why Nathan was given up for adoption. Kyoung-mi said she remembered going hungry as a child because money was so tight. “I heard that my mother was working at a construction company trying to help pay bills … but it was tough.” Nathan said. “They really did want to keep me, but … it was financial.”

Nathan’s birth mother never forgot the youngest she painfully gave away. Her dying wish was for her children to find their baby brother. The siblings tried for three years to glean any information about their youngest, first through the adoption agency and even the South Korean government, but, because of closed adoption regulations, they hit a dead end. They would have to wait until Sang-kil looked for them.

One burning question Kyoung-mi had for Nathan was whether he had lived a happy life. Nathan assured her that he grew up with an “amazing family.” He credited his adoptive parents for raising him to be the person he is today: happy, healthy, confident and ready to start a family of his own with Allison—they are considering adoption themselves.

Before they parted ways, and after many hugs, “Kyoung-mi kept asking when we’d see her again,” said Nathan. His siblings have offered to pay for his plane ticket to Korea and also invited his adoptive parents and sister to come. Nathan isn’t quite sure when he’ll be able to make the trip, but he said it’s definitely a journey he wants to make. It would be his first to his birth country since leaving as an infant almost four decades ago.

Now that Nathan is forming relationships with his biological siblings, with whom he keeps in touch through KakaoTalk and the group chat app BAND, he said he realizes his birth search was not just valuable to himself, but was also a great gift to them.

“They’ve been wondering about me for 38 years, whereas I didn’t know I had this family until just six months ago,” said the person who once thought he could go his entire life without digging into his past.

The experience has Nathan asking questions that never before crossed his mind. “How many families in Korea are still wondering where their babies are?” he said. He admits that he regrets not searching for his biological family sooner, more for his birth mother’s sake, “so she would have known I was all right and that I appreciated the choices [she and my birth father] made for me.”

Friends have encouraged Nathan, who wrote about his remarkable experience in a blog post on his photography business website, to make a documentary like Dan Matthews. The photographer is not sure if he’ll ever go so far as to make a film, but the reason he is sharing his story publicly is because he hopes, just as Matthews’ story touched and inspired him, his story can encourage other Korean adoptees—who number 200,000 worldwide—to do their own birth search.

“I just want everyone to know, don’t be afraid of it. There could be a happy outcome,” he said. “[Knowing] that a family back in Korea might be wondering, wishing and hoping to find out how their adopted baby is doing, it’s worth it.”

Recommended Reading

“November Cover Story: Dan Matthews”

“Anais & Sam: A Love Story of Twin Sisters Reunited After 25 Years”

“Faces of Adoption: A Photo Essay”

“Why a Generation of Adoptees is Returning to South Korea”

___

This article was published in the April/May 2015 issue of KoreAm.