In mid-February, in California’s San Fernando Valley, a 16-year-old Asian American boy was attacked and sent to the emergency room by classmates who accused him of having the coronavirus.

On March 14, in Midland, Texas, a man brutally stabbed an Asian American family of three—including two children, aged 2 and 6—because he “thought they were Chinese and infecting people.”

On March 28, in Manhattan, New York, four teenagers shouted slurs at a 51-year-old Asian woman on a city bus, then beat her with an umbrella until she required stitches.

On April 5, in Brooklyn, New York, a 39-year-old Asian woman was doused with acid outside of her home by a man who’d been sitting in wait for her. She suffered severe burns across her body, face and hands.

These are just a handful of the thousands of reported cases of anti-Asian hate and violence that have erupted across the nation in the past few months, as the novel coronavirus has claimed over 50,000 American lives and confined millions of us to our homes. The two parallel epidemics, COVID-19 and xenophobic bigotry, have paced one another in growth, the latter deliberately fomented by national leaders—foremost among them the President of the United States—desperate to distract from their own mistakes by associating the disease with the country that first experienced its impact. By demanding that it be called “the Chinese virus,” they’ve chosen to put a face and a race on an invisible scourge, one that looks like many of us whose heritage stems from East and Southeast Asia.

History tells us that this isn’t a coincidence. From the dawn of migration from Asia to the United States, and over the course of two centuries since, populist demagogues have responded to external threats by turning citizens against their Asian American neighbors.

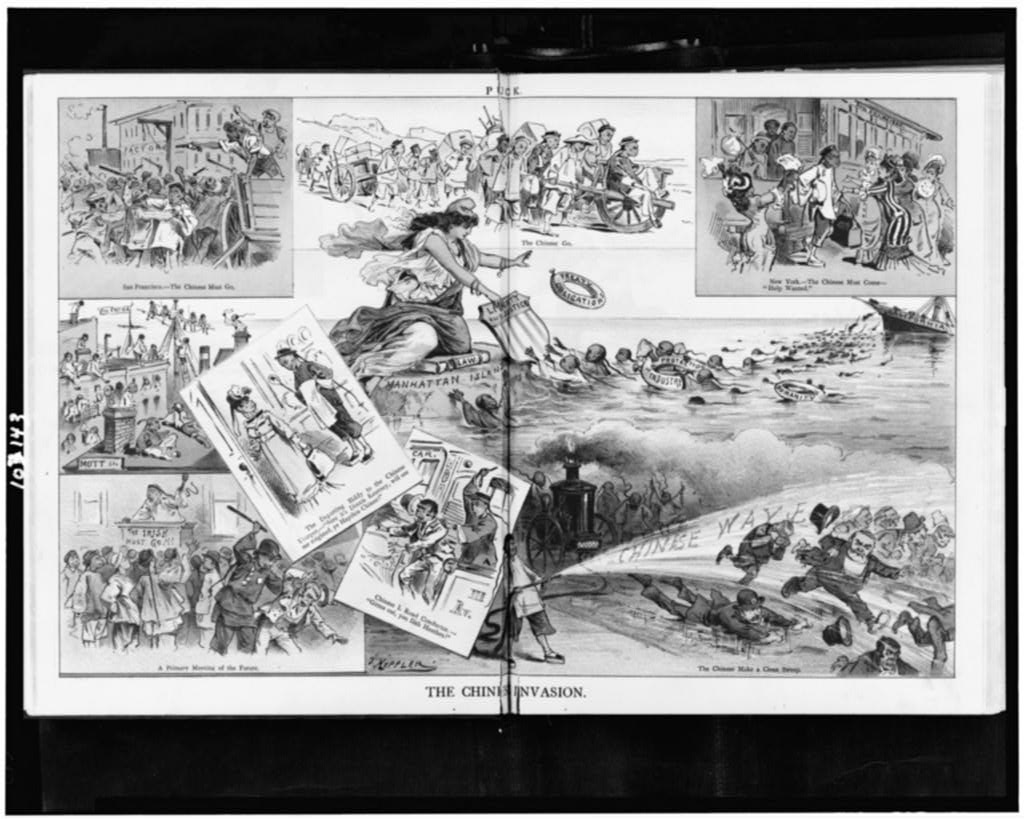

In the 19th century, labor leaders and political bosses blamed “Chinamen” for stealing American jobs and bringing “disease and depravity” to the slums where they were allowed to settle. The results were beatings, murders and right here in Los Angeles, on a street now renamed after the city itself, one of the deadliest mass lynchings in this nation’s history. In the 1871 massacre of the Chinese immigrant enclave living on a notorious stretch called Calle de los Negros, 18 men and boys of Chinese descent were murdered by a mob of over 500, who shot and hanged the neighborhood’s residents, mutilated their bodies and burned their stores and residences. Ten ringleaders were arrested; none spent a day in prison. Other bloody massacres would follow, in western towns like Rock Springs and Hells Canyon. None of the murderers in those assaults served time, either.

In 1882, as the anti-Chinese movement spread from the streets to the statehouses and finally to the federal government, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, banning Chinese from entering America. The law— the first, and still the only, major federal legislation to explicitly bar people of a specific nationality—made those already in the country permanent foreigners, unable to ever naturalize as American citizens, and doomed most to solitary existences without spouses or family. By 1924, the National Origins Act extended the ban on migration to all East Asians.

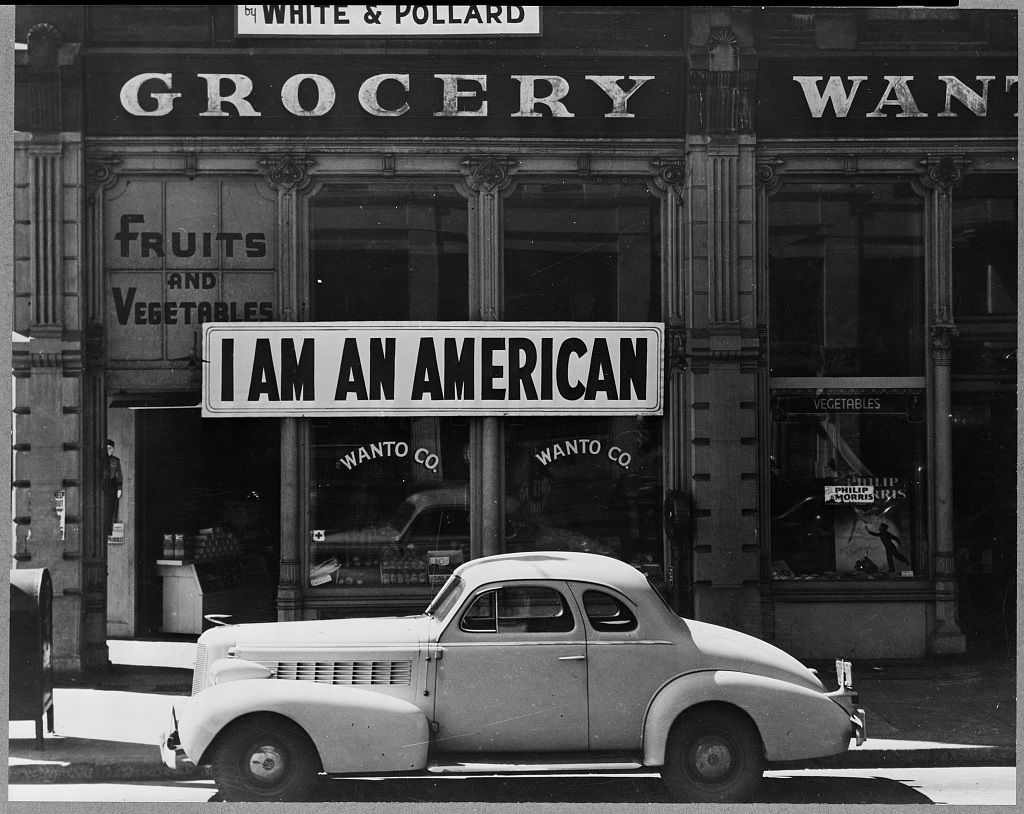

These laws would remain in effect for the next two decades, by which time a new “Asian threat” had risen in the form of Imperial Japan, spurring a new generation of populists to demand that Japanese Americans be punished for their racial and cultural connections to the enemy. The horrific consequence? Groundless incarceration for the duration of World War II of over 120,000 Nikkei, two-thirds of them American-born citizens, in internment camps surrounded by barbed wire and sentry towers.

Not a single Japanese American was ever found guilty of espionage or sabotage during the War. The darker truth is that the demand to remove Japanese Americans from their homes, farms and property was fueled by greed and jealousy. As one notable anti-Japanese advocate Austin E. Anson, managing secretary of the Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association, told the “Saturday Evening Post,” “It’s a question of whether the White man lives on the Pacific Coast or the brown men. They came into this valley to work, and they stayed to take over. If all the Japs were removed tomorrow, we’d never miss them in two weeks because the White farmers can take over and produce everything the Jap grows. And we do not want them back when the war ends, either.”

The close of the Second World War wasn’t the end of America’s war with Asia—far from it. The Fifties brought the Korean War, and the Sixties the Vietnam War; anti-Asian propaganda and dehumanizing tropes were recycled and reused across each of these conflicts and applied to new nations and peoples, proving racism and xenophobia to be endlessly renewable resources.

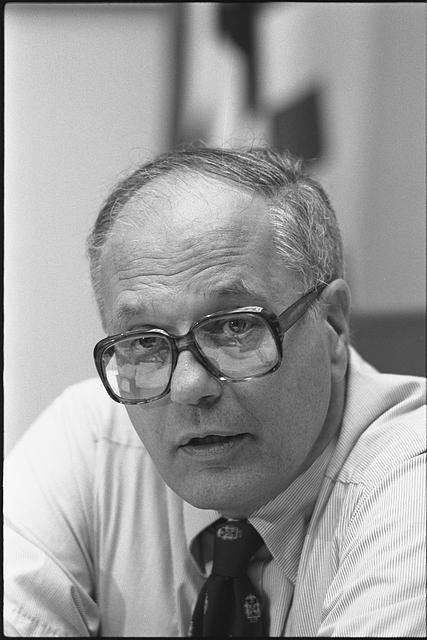

By the Seventies, Japan was back on the American populist radar, not as a military threat but an economic one, riding the success of its automobile and electronics industries to rapid growth. In 1980, Japan surpassed the U.S. as the leading automobile manufacturing nation in the world, triggering U.S. labor leaders and politicians to blame the nation for the loss of a quarter-million American jobs. Members of the United Auto Workers union took sledgehammers to Hondas and burned Japanese flags. Representative John Dingell, the legendary Democratic congressman from Michigan, infamously raged in a House caucus session about how his constituents were losing their livelihoods to the threat of “little yellow people.”

Amidst these appeals to anti-Asian bigotry, from 1980 to 1982, the percentage of Americans who had a negative view of Japan more than doubled to compose almost a third of the nation, with particularly intense hatred in the manufacturing centers of the Midwest. It shouldn’t be surprising that 1982 saw an event that proved pivotal to the political awakening of the Asian American movement: The murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit at the hands of two unemployed autoworkers, one of whom shouted, “It’s because of you little motherf-ckers that we’re out of work!” Chin wasn’t Japanese, or even Japanese American, but the killers didn’t stop to check his citizenship or ethnicity before beating him to death with a baseball bat.

But by the 1990s, that would have been moot anyway. The rise of China had shifted the epicenter of threat among American populists back to the Chinese, who were charged with fundraising skullduggery in the 1996 election of President Bill Clinton, accused of planting Taiwanese American scientist Wen-Ho Lee as a spy in America’s top nuclear research facility, and blamed for purchasing billions in American debt, allegedly to put a stranglehold on our nation’s economic future.

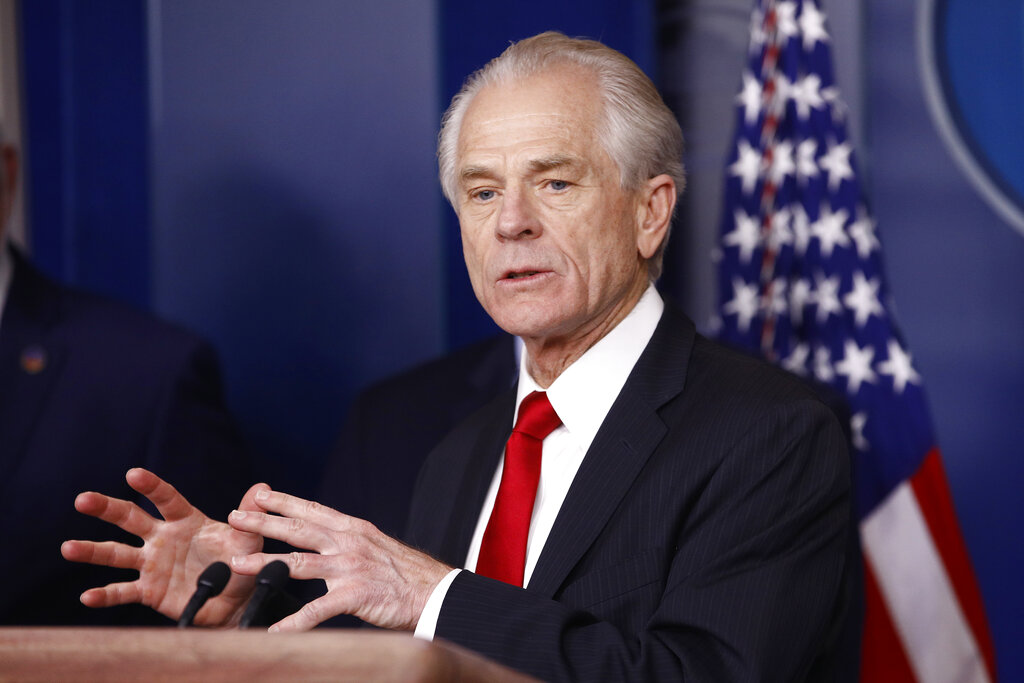

And China has been the obsessive focus of our current president, Donald Trump, since the earliest days of his campaign, in which he threatened to bludgeon China with his own version of a sledgehammer or baseball bat—tariffs on Chinese imported goods. Trump’s major economic policy advisor during his 2016 race was Peter Navarro, now his administration’s director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy. Navarro has long been one of the most virulent China-bashers in contemporary academia, writing such books as “The Coming China Wars“ (2006) and “Death By China” (2011), both predicting an inevitable conflict between the U.S. and the People’s Republic. (In 2012, Navarro even directed a documentary based on the latter book, whose opening graphics featured a CGI rendering of a flag-draped United States being stabbed to death by a knife labeled “Made in China,” causing the screen to wash red with blood.)

Within the Trump White House, Navarro has found common cause with Stephen Miller, the chief architect of many of the administration’s most brutal anti-immigrant policies, from the “Muslim Ban” to the policy of separating refugee children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border. Together they have called for new policies of Chinese exclusion, demanding an end to visas for overseas students from China and in the early days of the COVID outbreak, calling for a complete halt on all inbound Chinese travel to the United States for a 12-month period or more.

In short, the modern call to anti-Asian hatred is coming from within the house—the White House. And it seems clear that in his bid for re-election after his catastrophic response to the coronavirus outbreak, Trump intends to stoke fear and hatred against China, while attaching blame to the Chinese government for the disease’s rapid spread. Trump pulled U.S. funding for the World Health Organization, the designated global entity overseeing international cooperation on medical and public health issues, accusing it of being too “China-centric.” Most recently, in his first campaign advertisement aimed at his Democratic rival, Joe Biden, Trump slammed the former vice president for “standing up for China … while China cripples America.” Hidden in the ad, almost subliminally, is a screenshot of Biden greeting an Asian man standing in front of a Chinese flag. That man happens to be Gary Locke, former governor of Washington, former secretary of Commerce and the first Asian American to serve as U.S. ambassador to China.

Meanwhile, his surrogates in the Republican Party are amping up the China blame. Senator John Kennedy of Louisiana tweeted that, “If you turned President Xi upside down and shook him, the WHO would fall out of his pocket. China lied, a lot of people have died, and the cover up [sic] is not right.” His fellow Republican senator, Tom Cotton of Arkansas, went further, stating on Fox News that “we need to ask the question” of whether a conspiracy theory alleging that the novel coronavirus actually originated in a Chinese biowarfare lab had any truth to it, and declaring that America would “hold accountable those who inflicted it on the world.”

The past has shown us the path by which populist bigotry sparks at the edges of society, seeps into alleys and shadowed places as isolated episodes of violence, bursts into the main streets as mob hysteria, and is eventually embraced by elected leaders and forged into official propaganda and racist policy.

The election of Trump to the presidency and the devastating crisis of the COVID-19 outbreak have accelerated us down that path. It’s not hyperbole to say that today, our Asian American community may be facing our greatest threat in generations: a threat to the societal successes we’ve won, to our livelihoods, to our very lives.

At its surface, the political campaign we’re beginning to see waged against China may seem like a matter of foreign policy; inevitably, however, the transformation of any nation into an enemy of the American republic has domestic implications, fostering hatred of its people and suspicion of those with cultural ties, or even just vague physical resemblance, to them.

That transformation has already begun. According to a Pew Research Center poll released in August 2019, long before anyone was aware of the coronavirus, 60 percent of Americans already saw China negatively, versus just 26 percent holding positive views. A quarter of all respondents believed China was “our greatest enemy,” putting it in a tie with Russia.

Some have suggested that the way through the growing darkness is to ignore it, or to overcome it by proving our worth, our commitment, our belonging. But America is our right by birth or naturalization or residence, by sacrifice and stakehold; we shouldn’t have to demonstrate it more than any other group in this country. Doing so tacitly endorses a system that ranks Americanness on a sliding scale, one that demands non-white communities clamber over one another for proximity to whiteness, and that threatens to strip the status of “real American” away whenever this nation faces risk or crisis.

For us as Asian Americans, this is a time to be alert and vigilant—to raise our voices, not lower our heads. We must be unafraid to call out and document racist acts when they occur, not just to ourselves, but to others. We’ll get through this. We’ll pass this test. But we can only do it if we join forces within our communities, and beyond. Because while COVID demands that we distance ourselves from one another to survive, bigotry and xenophobia demand that we come together.

This article appeared in “Character Media”’s April/May 2020 issue. Check out our current e-magazine here.