Story by Julie Ha

Following the North’s artillery shelling of South Korea’s Yeonpyeong island last week, some global headlines screamed that the Korean peninsula was nearing the brink of war. Meanwhile, many who follow North Korea closely expressed a more measured view: here we go again.

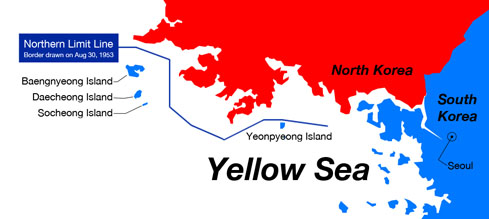

Indeed, there was a déjà vu quality to the most recent conflict, which took place Nov. 23 on an island in the Yellow Sea, just south of a maritime border that has long been the source of tension between North and South. At about 2:30 p.m. that day, North Korea fired multiple rounds of artillery shells across the western sea border onto Yeonpyeong island, home to about 1,500 residents, mostly fishermen and their families, as well as a South Korean military base.

The North, believed to be targeting military installations on Yeonpyeong, justified its shelling as a response to the South’s “live fire” military exercises on the island, about seven miles from the North’s shores, earlier that day. Pyongyang had warned its neighbor of retaliation if the exercises went ahead.

The attack killed four South Koreans, including two marines, injured about 20, and leveled homes and buildings. It’s unknown what damage the North sustained after the South’s military returned fire in an artillery exchange that lasted about an hour.

Although the incident was often referenced in the media as the most egregious attack on Southern territory in decades (those killed included two civilians), many analysts have been quick to point out that such violence near this maritime border is also nothing new.

“This is about turf, turf warfare,” said John S. Park, a Northeast Asia specialist at the Washington, D.C.-based U.S. Institute of Peace. “This is a case where the two Koreas were trying to assert their rights.”

Pyongyang has long contested this Northern Limit Line unilaterally drawn up by the United Nations Command in August 1953, after the Korean War; the North insists the border should be further south. As a result, clashes in the waters have erupted time and time again.

A year ago last month, South Korean ships fired upon a North Korean vessel sailing in the disputed waters, inflicting serious damage. Other naval clashes in 1999 and 2002 resulted in the deaths of a more than 40 sailors on both sides. Although Pyongyang has denied culpability, the March sinking of the South Korean naval vessel Cheonan, which killed 46 sailors, occurred in these same contested waters, and some experts theorize it may have been an act of revenge for a previous skirmish.

“The North Koreans have always hated this line,” said David Kang, director of the Korean Studies Institute at the University of Southern California. “This [latest incident] could be a result of yet one more burst of North Korean anger at South Korean moves.”

The Peace Institute’s Park noted that the Northern Limit Line, often discussed in the context of security issues, also has a significant economic component. The waters along this border are ripe crab grounds for fishermen on both sides of the line. “As trivial as it sounds, [this is] an important revenue generator for North Korea,” said Park. The money earned by these fishermen, who sell the prized blue crabs to China, goes to a North Korean state trading company, whose operating budget is used to line the pockets of senior Pyongyang officials, “so this is substantial.”

In 2007, during the Roh Moo-hyun administration, which followed a “sunshine policy” of open-ended engagement with North Korea, there was talk of turning this problematic boundary area into a peace zone, said Park. Roh and the North’s Kim Jong-il pledged to discuss a joint fishing area, for example. But after the progressives were voted out and current South Korean President Lee Myung-bak’s more conservative party voted in, “any type of framing of this area as a peace zone was scrapped,” said the analyst.

The most recent border clash comes amid heightened tensions on the peninsula, stalled nuclear talks among the Koreas and the United States, and just days after Stanford scientist Siegfried S. Hecker’s revelation that he had visited a modern North Korean plant that was enriching uranium.

Internally, North Korea is also experiencing significant changes, as dictator Kim Jong-il, who is believed to have suffered a stroke in 2008, has begun the process of transferring power to his third son, Kim Jong-eun. In October, Jong-eun was named to his first official political and military posts.

Kang said it’s possible that the North Korean military is acting more aggressively these days in order to “bolster domestic legitimacy” for the successor.

“Kim Jong-eun is less than 30 years of age and has no nationalist or military credentials. Thus, allowing him to be seen as the mastermind behind a number of provocative moves towards the South is one way in which he can attempt to earn legitimacy with the powerful North Korean military,” said Kang.

Although the Yeonpyeong incident has set off alarms in Washington and internationally, Kang said it is fundamentally different from a major North Korean military mobilization with intent to invade its neighbor.

“In fact, skirmishes occur precisely because they are highly unlikely to cascade into a major war between the two sides,” he said. “A war would be devastating for both sides, and although both sides would like a unified peninsula, neither has seen war as a viable option for achieving that goal for almost six decades.”

As for a South Korean and American response, most experts seem to agree that there are no good options. “How do you sanction the most heavily sanctioned area of the world?” Park asked rhetorically, referring to existing United Nations sanctions imposed on the North in response to its past nuclear weapons tests. There has been discussion in Washington about getting the United Nations Security Council to issue a strong statement condemning the North, but Park said such a move would likely not get support from key member China, which has been bailing out the isolated nation and been reluctant to censure Pyongyang’s actions this time and after the Cheonan incident.

As with the latter incident, the United States and South Korea responded to the latest provocation with joint military exercises in the Yellow Sea, and the two Koreas again exchanged tough talk about retaliation for further provocations.

Beyond the rhetoric and posturing, the latest clash between the Koreas, on a more basic level, has reminded many with ties to the peninsula of a deeper pang. Louisa Lim, a reporter for NPR, captured that sentiment when she quoted a villager on Yeonpyeong, who like many other shelling victims she interviewed did not appear angry at his Northern neighbors. “The North Koreans are our brothers,” the man told Lim, “and our enemies.”