By Michelle Woo

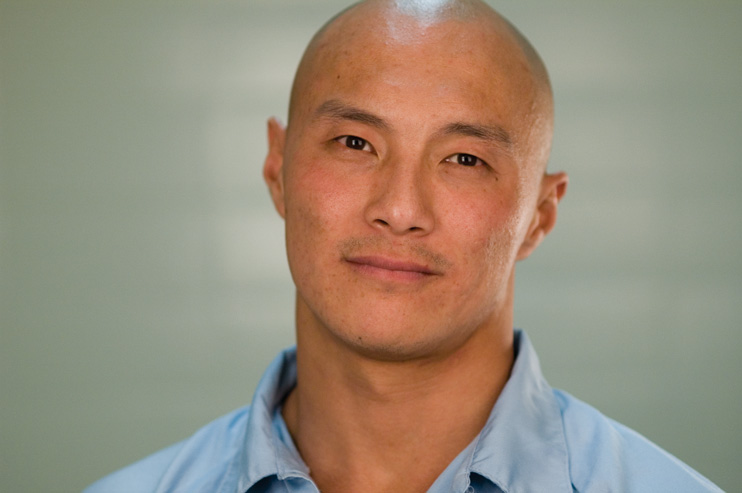

> Photographs by Eric Sueyoshi

Tim Yu stands over his daughter’s cage-like hospital bed, shielding her closed eyes from the artificial lights. Her cheeks are puffy from the medication. She squirms as if she’s having a bad dream. A plastic tube is connected from the chemotherapy drip all the way to a vein in her tiny leg. Numbers move up and down on the blood pressure monitor. Time passes slowly.

Behind the thin curtains are the sounds of children crying and multiple televisions buzzing at once. Tim sits down next to his wife, Susan. Wearing bright orange visitor’s stickers, they stare at the digital machines.

“There’s a lot of waiting. There’s a lot of silence. We try to be as normal as possible, but we’ve had to redefine ‘normal,’” Tim says.

Just five months ago, the Yus experienced the biggest miracle of their lives: Susan gave birth to triplet girls. But their excitement soon turned to panic when Elyse, the eldest of the three, was diagnosed with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), a deadly blood disease that strikes approximately one in a million.

Without treatment, the disease is fatal. The median survival time reported in various studies is two to six months after diagnosis. While chemotherapy and other medications can buy Elyse more time, a bone marrow transplant is the only hope for a cure.

But the odds of finding a bone marrow donor match aren’t on her side. A sibling would be the first option, but her fraternal sisters are too young to donate and could also carry the disease. Because tissue type is inherited, there is an 80 percent chance that Elyse’s match will be Korean. Yet ethnic minorities are largely underrepresented in the bone marrow donor registry. Of the 6.5 million donors registered, 400,000 are Asian and only 50,000 are Korean.

Gazing at their fragile newborn girl, Tim and Susan say these numbers need to change.

***

The couple met at a church in Los Angeles 18 years ago. Tim was a college freshman. Susan was a high school senior. They married in 2001 and recently moved to Canyon Country, Calif.

For four years, they struggled with infertility. Susan tried hormone shots, artificial insemination — the works. As a final effort before turning to adoption, she underwent in vitro fertilization.

Finally, the Yus got their wish — and more.

“The doctor started mumbling something,” says Tim, 36, recalling the moment he saw three little heartbeats on the ultrasound monitor. “They looked like grains of rice beeping. It was shocking. The doctor said the chance that three eggs would take was one in a million. We thought, ‘This must be divine intervention.’”

On Feb. 1, 2007, three babies entered the world: Elyse, Faith and Erin. They were perfect, doctors said.

As they had anticipated, life became crazy. Susan, 35, would clear out the shelves of diapers at Target. Grandparents were on hand around the clock, working in shifts. The Yu house was filled with chaos, laughter and joy.

Everything changed on May 1. Elyse came down with a fever that wouldn’t budge with Tylenol. Over the next few days, it spiked to 104 degrees. Tim and Susan rushed her to the hospital, where her body was pricked and punctured with needles. Through a number of blood tests, they found that her platelet count was dropping rapidly.

Elyse was moved to the Childrens Hospital Los Angeles. At night, her parents slept on a cot near her bedside.

Doctors found that Elyse’s spleen and liver were enlarged — five times the normal size — which quickly led them to a diagnosis. On May 6, Tim and Susan were taken into one of the hospital’s conference rooms, where they learned all about HLH.

As the doctor left the room, Susan broke down and cried.

“I was barely even adjusted to being a mom and to being a mom of triplets,” Susan says. “Now I had to deal with my child possibly being terminally ill. My life just turned upside down.”

***

With HLH, Elyse’s body has too many histiocytes and lymphocytes, both of which are white blood cells that fight infection. These cells go haywire and attack healthy cells, causing damage to a variety of organs.

“Her body is basically killing itself,” Tim says bluntly.

HLH is usually inherited, but it can also be caused by certain diseases or infections. The disorder primarily affects babies, but it can be found in patients of all ages. The most common early symptoms are a fever, an enlarged liver and an enlarged spleen. HLH is often referred to as an “orphan disease,” meaning that it strikes too rarely to generate government-supported research.

Chemotherapy can control the disease, but it is not a cure. Elyse’s only shot at remission is a bone marrow transplant from a volunteer donor. Bone marrow is the soft tissue found in the hollow interior of bones, which produces new blood cells.

“[With a bone marrow transplant,] you’re removing the bone marrow that has the defect in it and replacing it with bone marrow that produces healthy cells,” says Jeffrey Toughill, president of the Histiocytosis Association of America, a New Jersey-based organization that supports those dealing with rare histiocytic disorders such as HLH.

Thirty percent of patients needing a transplant find a matching donor within their families. Tim and Susan both joined the bone marrow registry 15 years ago when a friend was diagnosed with leukemia. Neither, however, was found to be a match for baby Elyse.

Frightened and overwhelmed, Tim and Susan decided to hold a meeting with family and friends. Soon, their living room was swarming with people anxiously waiting to hear how they might be of service. Standing with markers and presentation easels, they brainstormed outreach projects and assigned various tasks. Some would help set up bone marrow drives at local Korean churches. Others offered to help babysit Faith and Erin. Many went home and sent e-mail messages to everyone in their address books, urging them to register as donors.

Tim also asked his cousin, a documentary filmmaker, to make a video of Elyse’s story. It’s now posted on YouTube and on Elyse’s Web site, www.elyseyu.com, which includes details on bone marrow drives throughout the nation, information on the medical condition and frequent updates from Tim and Susan.

Tim says he didn’t think twice about going public with Elyse’s story, despite some early anxiety expressed by his parents. Sometimes, when genetic illnesses strike, first-generation Korean Americans opt to keep quiet. They don’t want to be stigmatized as having a disease.

“But if you don’t tell people that you need help, you won’t receive it,” Tim says.

So far, more than 9,000 people have visited Elyse’s Web site. More than 700 have registered as bone marrow donors at drives held across the nation. Each night, Tim clicks through a roundup of e-mails, reading messages of encouragement and updates on how people are trying to help.

One woman wrote that she wanted to set up a donor drive at a church in Korea. Another wanted to know whether, at the age of 73, she is too old to donate her marrow. (To qualify as a donor, you must be between the ages of 18 and 60 and meet certain health guidelines.) Many simply tell Tim and Susan that they are being prayed for.

“It’s amazing,” Tim says. “We’re getting support from complete strangers. The word is spreading like wildfire.”

Sharon Sugiyama, director of Asians for Miracle Marrow Matches, a Los Angeles-based organization that has coordinated many of the drives, says that while Elyse’s story has captured the hearts of many, with impressive donor turnouts, what’s most important is that those who have registered will follow through with the transplant if called upon. Sugiyama says that in the Asian American community, an alarming number of donors back out once they’re matched. The statistics: 75 percent of Caucasians in the registry consent to the procedure when matched, while only 40 percent of Koreans follow through.

“If the donor isn’t willing,” says Sugiyama, “it’s like false hope.”

***

For Tim and Susan, each day begins the same way. Susan wakes up at 8 a.m., lifts Elyse onto a table in their bedroom, and flushes her PICC line (the IV connected to her leg) with Heparin to prevent her blood from clotting. She then loads up several syringes with various medications, including Decadron, a chemotherapy drug that makes her hungry all the time; Enalapril, which controls her blood pressure; Nystatin, an anti-fungal agent; and, on Saturdays and Sundays, Bactrim, an antibiotic that gives her horrible diarrhea. Susan checks off each dose on a homemade chart that is taped to the wall. So far, insurance has covered all the medical expenses.

Elyse is responding well to chemotherapy, but the side effects can be as harsh as the disease itself. Her face is so bloated that she can’t hold her head up without assistance like her sisters can. She has deep sores from the diarrhea. She is often nauseous.

Susan says they must call the doctor every time something seems abnormal — if her breathing seems off, if she’s breaking out in a cold sweat or if she looks a little pale. But most of the time, Elyse just cries.

“It’s frustrating,” Susan says. “I can’t tell what’s bothering her. I don’t know if it’s a dirty diaper or if it’s something more. I can’t ask her. She can’t tell me.”

Tim and Susan have built their routine around Elyse’s weekly hospital visits and daily treatment, but sometimes, they feel that their strength is wearing thin. In mid-June, they took Faith and Erin to the hospital for a blood test to see if they also carry the gene for HLH. As of press time, they have not yet received the results.

“There’s that fear — what if they have it, too?” Susan says. “It was so difficult watching the two of them lying on the doctor’s tables, screaming and crying as doctors drew four vials of blood. I don’t know how I’m doing this.”

***

With a bone marrow transplant, HLH patients have a 50 to 60 percent chance of survival, Toughill says.

“We still have a long way to go,” he adds. “I’ve talked to families whose children are doing well. But you always hold your breath. Sometimes, [HLH] can return.”

A quick Internet search brings up a number of family-built Web sites dedicated to infants with HLH. Through the months, some sites have turned into memorials. All begin with the same story: the high fever, the string of medical tests, a frantic search for a match.

“Oh, it was a nightmare,” says Cecilia Olsson, grandmother of a baby girl named Anna in St. Louis.

Anna was fortunate enough to undergo a bone marrow transplant, but about three weeks later, she died unexpectedly at 6 months and 19 days. “We don’t know what happened,” Olsson says.

A number of complications can occur during a transplant, including severe inflammatory reactions, hemolytic anemia and graft-versus-host disease. Some children who are diagnosed late may have severe and irreversible brain damage even if a transplant is successful. After a bone marrow transplant, patients are more susceptible to infection and bleeding.

In the midst of their questions and fears, Tim and Susan are still able to find little moments to embrace their lives as new parents. One Sunday afternoon, Susan dressed the three girls in pink, laid them on the bed and giggled as she took pictures.

“The joy outweighs everything,” Susan says.

They say that Faith is the expressive one, Erin smiles all the time and Elyse is very strong. They say their family, their friends and their faith in God are what keeps them going.

“We believe that there is a purpose for everything,” Tim says.

At night, Susan puts Elyse to bed and lingers for a moment. She says that all those dreams she had while she was pregnant — taking her daughters to the park, giving them ballet lessons, encouraging them to play an instrument — all faded away.

“I stand next to her crib at night while she’s sleeping, wondering if she’s going to make it through the night,” she says. “I wonder whether the transplant is going to take place. I wonder whether there’ll be complications with the treatment. I wonder what the recovery process will be like, how long it will be until she feels normal.”

When morning comes, the fight continues.

Becoming A Bone Marrow Donor

1) Join the National Registry

Complete a consent form and provide a swab of cheek cells. The registry is searchable by patients worldwide.

2) Find out if you are a match

Further testing determines whether you are a patient’s perfect match. The donor decides whether or not to continue.

3) Donate

During the procedure, a small amount of marrow is collected from your hip bone using a needle and syringe. Anesthesia is used.

Afterward, you may be sore for a few days to a few weeks, but normal activity may be resumed. Your marrow replenishes itself within a few weeks.

Source: Asians for Miracle Marrow Matches, www.asianmarrow.org

More Ways To Help

Aside from registering as a bone marrow donor, here are some other ways to support Elyse and the fight against rare histiocytic disorders such as HLH.

• Host a bone marrow drive

E-mail drive@elyseyu.com with a date, time, location and a number of potential donors. A representative from Asians for Miracle Marrow Matches will contact you.

• Donate your frequent flyer miles

Through the Northwest Airlines AirCares program, you can donate airline miles to the National Marrow Donor Program. The NMDP uses these frequent flyer miles to fly unrelated marrow and cord blood transplant (also called BMT) recipients and their caregivers to their transplant centers free of charge. For details, call (800) 327-2881 or visit www.nwa.com/cgi-bin/wp_donate_aircares.pro.

• Make a contribution

Support the Yu family by sending your donations to: New Life Community, c/o Elyse Fund, 846 S. Union Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90017.

All proceeds will be used toward promoting bone marrow drives and medical expenses

• Golf, walk or hike for a cure

Visit www.histio.org for upcoming events that support awareness and the search for a cure to rare histiocytic disorders.