By Ki-Min Sung

> Photographs by Eric Sueyoshi

Yul Kwon holds court over dim sum in Los Angeles three weeks after winning the physically and mentally grueling CBS reality show “Survivor.” Anything cooked and served on a plate tastes much better than the coconuts and raw fish he subsisted on for 39 days on the Cook Islands in the South Pacific.

Sitting around the family-sized table is a bevy of fans, among them an actress, a TV producer, three former beauty pageant contestants, a big-time movie producer, a network television executive, and two Smashbox cosmetics developers, one with her sister, having lunch before trying on wedding dresses. Yul spends time with everyone, learning about their interests as he crouches next to their seats or chats across the table. As he socializes, he gets pulled away from the table, twice, by acquaintances from his past, and goes through another round of introductions.

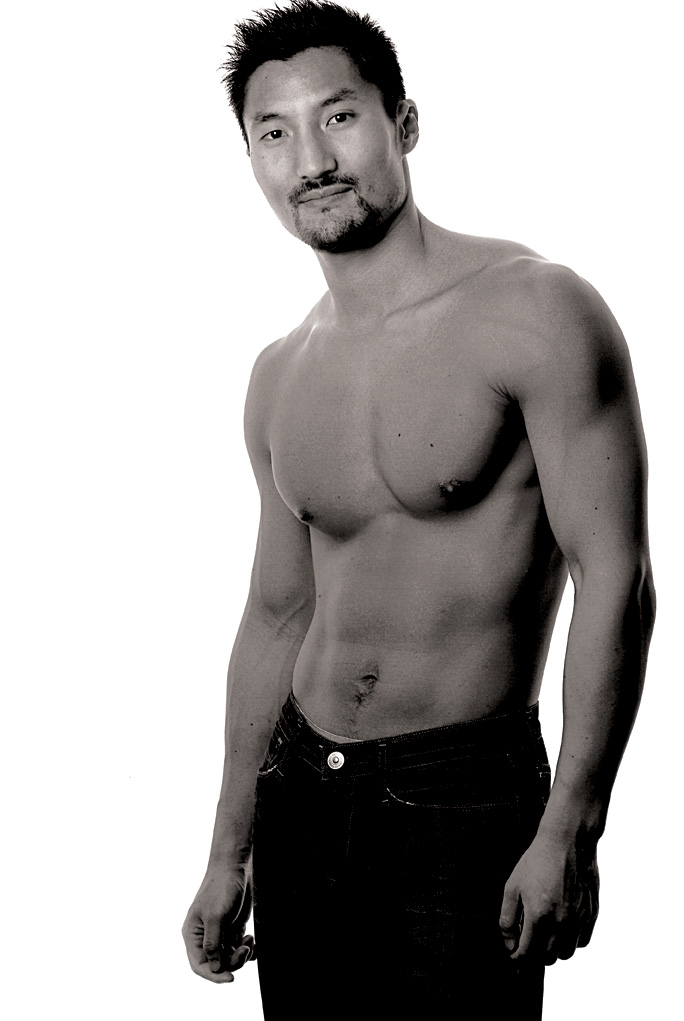

It’s just another one of the meet-and-greets Yul has had since he and his abs spent about three months in American homes nationwide.

He’s one million dollars richer, that much sexier, and has shattered stereotypes about Asian American men in the media. Yet he’s still a decent guy looking for a higher purpose in life.

“I’m pretty sure of what kind of person I am,” Yul says, “and I don’t think this whole thing is going to change me in terms of my values and the way I treat people, and my goals in life.”

Yul wasn’t one of the thousands of applicants who submitted videotapes of themselves for the “Survivor” tryouts. He and his Korean American ally, Becky Lee, were recruited when “Survivor” producers turned the game into racial Darwinism. Four teams grouped as Asians, Latinos, African Americans and Caucasians started the contest in separate tribes.

Yul says that producers couldn’t find enough Asian Americans for this 13th edition of the show, and that’s when a friend referred Yul and his abs to the casting agent. He says the participants weren’t told that they would be separated by ethnicity until the day before landing on the island, although the conveniently even number of players spread across the racial divide was suspect. However, instead of walking away in disgust, Yul saw an opportunity.

“I’ve always felt that we were underrepresented on TV to the extent that we were represented in a very negative light,” Yul says. “I felt like it was such a golden opportunity to change things a little bit.”

Yul wanted to change the stereotype of the Asian American man in the media, so often depicted as socially inept nerds or kung fu masters. Breaking the stereotype is a message he repeats often in public.

“When I was growing up, I didn’t see a lot of people who looked like myself, who I could really emulate as someone who was very socially adept, successful and looked upon by people in different communities, not just his own, as being strong and articulate and a leader,” Yul says.

Yul just might be the person he longed for growing up.

***

The 39 days of “Survivor” concluded with a tribal council vote that came down to brains versus brawn. No contestant could match the physical prowess of Oscar “Ozzy” Lusth, described by fellow “Survivor” Candice Woodcock, as “half animal, half man, part fish, part monkey, part lord knows what.” Yul played the mental and social game so well that he was dubbed by the castaways as the “Godfather” and the “Puppet master.” Using his communication and strategy skills, Yul was able to sway people on all sides to vote his way.

“I tried to convince them that I wasn’t being the Godfather,” Yul says. “I wasn’t telling people what to do, and I wasn’t a dictator. But they didn’t believe it, and the more I tried to tell them that I wasn’t the Godfather, the more they thought I was lying.”

His strategy was so well-played, cast mates who were eliminated, some in part by Yul, and joined the final tribal council voted for him to win in the end.

But the path to victory was never easy. Yul faced elimination on a number of occasions because he was viewed as a threat. And then, halfway through the season, the odds were stacked two to one against his team following a mutiny. After the four racially based tribes (which lasted only two episodes) had been dispersed into two, the castaways were given the option to switch sides. Two of Yul’s white Aitu teammates chose to join the six on the Raro tribe (which included some of their former Caucasian brethren), leaving behind Yul, Becky, Sundra Oakley, who is African American, and Ozzy, who is Mexican American.

Dubbed the “Aitu Four” and vowing to be honest and to play an ethical game, Yul and his team began to win every challenge, picking off all eight Raro tribe members one by one. A noticeable pattern within Raro was that four of the eight who were minorities were eliminated first. Then, the Aitu Four’s cohesion was tested when they were up against one another. In a rare moment in reality television, and perhaps human nature, the Aitu Four opted for a skill-based tiebreaker instead of ganging up on any one member and voting that person out. Sundra lost the final challenge of starting a fire to Becky. Ozzy, Becky and Yul moved forward to the final tribal council to vie for the million dollars. Yul won, in a 5-4-0 vote, with Ozzy garnering the four.

In the finale, host Jeff Probst said the question he gets asked the most by fans is, what’s up with Yul and Becky? Their close alliance had viewers speculating over any love connections. The two insist that they are just friends and that living conditions on the island, where the opportunity to bathe is a prize, were not hospitable to any kind of romance.

“The idea of hooking up with someone was repulsive because we’re so gross and we’re so nasty, and I didn’t even want to touch myself,” Yul says.

It’s not unusual, however, for castaways to start physical relationships on the waterfront, as they spend days and nights together, their hard bodies barely covered. Candice Woodcock and Adam Gentry had their intimate onscreen moments. And, if Yul had hooked up with Becky on television, or any other cast mate, he would have broken another stereotype (Asian American men as eunuchs) by exerting his sexuality.

“I didn’t want to complicate my game by hooking up,” Yul says. “I mean, my parents are watching. All of my friends are watching, and if I were to get into some sort of gratuitous hook-up with some woman, I didn’t see how that would really further my own goals or interests within the game. I thought the best way I could change the image [of Asian American men] is to do well in the game.”

Needless to say, Candice and Adam didn’t make it to the final round.

However, Yul does admit one moment when he got intimate with another castaway.

“The closest I got to hooking up on the island was one night when I was really cold and my hands were shaking, Jonathan Penner, who was lying next to me, said, ‘Hey Yulie, uh, if you want, you can stick your hands in my armpits,’” Yul says. Jonathan explained that the warmest parts of the human body are the armpits and the groin.

“I shoved my hands in his armpits, and I was so happy,” Yul says. “It was a little slice of heaven.”

***

Off of the island, Yul and his abs get plenty of attention from the ladies. It doesn’t hurt that he was named one of the sexiest men alive by People magazine, just like that other marooned Korean American guy on TV with the abs, Daniel Dae Kim. But fame hasn’t driven Yul to become an Asian American Lothario. Instead of taking advantage of the newfound notoriety, he has managed to start a relationship with a 28-year-old woman named Sophie.

“I was always like, in the beginning, ‘If you want to be single, I completely understand. It doesn’t make sense for you to be tied down right now,’” says Sophie, who declined to provide her last name. “But I don’t think it rang a bell for him. So it was kind of neat.” The couple met through another Cook Islander, Brad Virata, who is friends with Sophie, and they began dating one week before the “Survivor” finale.

It’s been a hectic time for Yul, who juggles numerous photo shoots and interviews; even traveling to the Sundance Film Festival to speak on a panel on Asian American representation in the media.

“I just have to put aside what I know is the normal process of starting a relationship,” says Sophie.

But Yul also takes every measure to make Sophie feel as comfortable as possible. At a recent birthday party for Yul’s friend, Sophie was embraced by his circle of friends. And at a Sikh temple, where Yul gave a speech for a bone marrow drive, she was part of the conversation.

Former college housemate Anthony Lim, 29, says Yul is extraordinarily inclusive and kind.

“I thought Yul and I were best friends, but what I didn’t realize is that he has 50 best friends,” Lim says. “He clearly puts priority on friendship over anything else.”

On paper, Yul has formidable accomplishments: high school valedictorian, Stanford undergrad, Yale Law School, former consultant at McKinsey, policy analyst for Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.), and a consultant for Google. He and his abs also participated in the physically challenging U.S. Marine Corps Officer Training camp during college — without joining the Marines — just to see if he could do it.

What doesn’t appear on his résumé, according to Lim, is the devotion he shows to his friends. Lim recalls late-night study sessions when Yul would bring Lim his favorite snack from Juice Club. And then there were those long talks. “He’s a really insightful person and a really sensitive person,” Lim says. “I just found that the conversations we got into were really stimulating. He just got to the heart of what was going on, good and bad.”

In college, back in 1995, during the early days of the Asian American Bone Marrow Registry, Yul’s longtime friend, Evan Chen, was diagnosed with leukemia and could not find a match for a life-saving bone marrow transplant. Yul, with the help of his fraternity brothers at Lambda Phi Epsilon, headed what was the biggest Asian bone-marrow drive in the country at the time.

“We had exams, we had classes, and Yul just dropped everything,” says Lim, who was housemates with Chen and Yul. “He became all consumed, and it was very simple for him — ‘My friend, he’s sick and he needs my help.’ I think he just had this single-minded determination to run this bone marrow registry and get as many people involved in the movement.”

Chen eventually found a match and had the transplant. Friends and family thought he was going to improve, but his health took a turn for the worse, and he died in 1996.

Yul continues his involvement with the registry. In January, wearing a head cover and an honorary scarf, he gave a speech in a Sikh temple in Fremont, Calif., to encourage bone marrow registration. Yul was asked to appear at the temple by a Christian couple who flew out from their home in Kansas to find an Asian bone marrow match. Their toddler son, Rohan, who has a rare immune deficiency syndrome, needs a transplant right away.

“Yul, you’re so nice to do this,” said Carol Karer, Rohan’s mother, as she gave him a hug outside of the temple.

“I know what it feels like to be in the situation,” said Yul.

***

Away from the crowds, at his brother’s home in Danville, Calif., another side of Yul appears — that of a loving son. Yul has a photo shoot, this time for KoreAm. He has already posed for countless photos, so he knows the camera and knows which muscles to flex. But no one makes him crack a smile like his mother.

“Hellooo?” Clara Kwon says, holding an angel Christmas ornament, trying to make him smile for the camera.

He smiles and shows teeth.

“Aigoo!” she says, as she makes the angel hop in the air, closer and closer to Yul.

He bursts out in laughter and smiles.

“If you become a model, I think you will be the best model!” Clara says.

“I only have one fan,” he says.

Despite his newfound celebrity and love from the camera, Yul says he has no intentions of going Hollywood, a path not unheard of for many former “Survivors.” He wants to use his 15 minutes of fame to raise awareness for causes he cares about. His options are wide open right now. Although he now has $1 million, he’s technically unemployed. His prowess on “Survivor” excites many who envision a political career for the so-called Godfather. Politics is something he’s considering — Yul has been involved with campaigns for political candidates — in addition to going back to the corporate world. But he has a strong interest in nonprofit work, and believes his heightened profile can help bring awareness to issues important to him.

“He’s not just one of those people who’s very smart so he does what he wants to do to be successful,” says former college girlfriend Yidrienne Lai, who is also a close friend. “I think he has an emotional depth that makes him very special. He wants to do the right thing.”

****

Under Her Own Light

Rebekah “Becky” Lee, arguably, garnered one of the worst reputations on “Survivor.” Viewers saw an Asian American woman clinging to the “Godfather,” Yul Kwon, and benefiting from his every move. They saw a quiet Asian American woman who didn’t win challenges. They saw the Asian American woman who had Yul’s immunity idol in her back pocket, even though she didn’t find it. The biggest injustice was that Becky made it past all of the elimination rounds to become one of the final three contestants, positioned to win $1 million. Cast mates called her a “coattailer.” In the final round of “Survivor,” she remained in the shadows of two dominant men, failing to get even one vote.

What viewers didn’t see is a woman driven to succeed, who also uses her humanity as a domestic violence worker to bring people together. They didn’t see the friendship and kindness she offered to her cast mates. And, that she is hardly a quiet Asian woman.

“I’m such a focused person,” Becky says. “I’m even watching what I say in confessionals because I’m afraid one little word and one little phrase can be twisted. That’s television — they’re going to use anything juicy.”

In the penultimate episode, either Becky or Sundra Oakley was going to be kicked off the island. And the members of the “Aitu Four” said they would vote for a tiebreaker challenge to decide whom. But Becky kept a contentious secret: She could go on to the finale because Yul had offered to her the immunity idol soon after he found it. But when host Jeff Probst asked Becky if she had the idol, she replied no. Back stabbing is par for the course on “Survivor.” It wasn’t something Becky wanted to resort to.

“If I accepted the idol, how would Americans feel?” she says. “I said, ‘Yul, if I take this, not only are people in our alliance going to hate us, I can’t go to work and do women’s rights work and face my family and my friends as this idealistic person who wants change.’ It’s not who I am.”

Instead of taking the easy way out, Becky faced Sundra in a final challenge. In a scene that will be remembered by “Survivor” fans for its futility, Becky and Sundra had to start a fire using a flint, coconut husk and wood. An intense contest turned into a long waiting game, as neither contestant could generate enough sparks from her flint to alight their coconut husks. Then, they were given a box of matches, still to no immediate results. Everyone else watched as minutes turned into hours. Sweat beaded on both women’s faces and bodies while the tribal council and Probst yawned between frustrated and glazed expressions. Sundra ran out of matches and Becky ended up winning the contest. But what the editing room left out was that when Sundra ran out of coconut husk, Becky gave Sundra some of hers. And that, when Sundra ran out of matches, and hope, she cheered on Becky.

Becky may be known by the public as the “coattailer” who took hours to start a fire, but she sees herself as someone who became a role model. She was recruited to join “Survivor” three weeks before the show began. She underwent intense training during that short period by memorizing pressure points to quell hunger and pain, working with a military trainer and bulking up. She played an ethical game.

Becky wanted to raise awareness about domestic violence and use the money to help women. And, along with Yul, “Survivor” became an opportunity to show teamwork and community cohesion among Asian Americans.

“We represented our Korean community well, as two Asian Americans purposely helping each other so they can get this far together,” Becky says.

***

There were hardly any Asians in the communities where she grew up. Becky was born in New York, but moved to Pittsburgh as a child. She graduated from the University of Michigan and then from law school in Pittsburgh. Her Korean community was at church, where she taught Bible study and went on missions. Growing up, she felt that young Korean Americans were so driven to succeed, they lost sight of the bigger picture.

“We talk about our parents coming over here because they wanted to provide a better life for their kids and work hard as individuals,” Becky says. “But at the same time, we’ve lost that community. Why can’t we do it together?”

Today, she lives out the ideas of community and helping others living and working as an attorney in Washington, D.C. She didn’t win $1 million, but walked away with $85,000 for finishing in third place. She is using her winnings to start the Becky Lee Women’s Support Fund, a nonprofit organization to help victims of domestic violence. She says that the Asian Americans are often misunderstood by the mainstream domestic violence community because it doesn’t adequately address cultural barriers, such as the old world patriarchal pecking order and immigrant issues. She says those inadequacies are why she works to address domestic violence among immigrant women.

But Becky also says Asians can do more to address the problem amongst themselves.

“We have a lot of pride in our community, and we don’t like to talk about things,” Becky says.

As for probing questions about her and Yul? Becky says they are just friends.

“I don’t know what the future holds, but we both were in it to win the game,” Becky says. “It never crossed my mind at the time because it was a game. When you meet someone who has great intentions or has a good heart, having that kind of relationship where you trust someone at face point, is very nice. And it usually takes years to cultivate that, and I hold it very valuable.”