Governments throughout this country have deemed restaurants as essential, allowing these businesses to stay open during the COVID-19 outbreak. But the announcement came with a major caveat: delivery and to-go orders only. While larger food corporations such as McDonald’s and Domino’s are experiencing an economic boom, most restaurants that cannot withstand the loss of revenue by turning into to-go-only facilities have had to shut down for the remainder of the quarantine, and those are the fortunate ones. A third of restaurants nationwide have had to close their doors permanently.

“What we do have is the fact that the government does recognize us as an essential business,” says Ming Tsai, chef and owner of Boston’s Blue Dragon, which is closed for everything but no-contact pick-up orders. “People don’t realize, to close a restaurant you don’t just lock the doors and walk out. You have so much food that you have to work with; you can’t just leave it in there to spoil.”

Tsai, a renowned celebrity chef with his own PBS cooking show on his resume, has decades of experience in the business. But for younger chefs who just happened to open up a new restaurant shortly before the coronavirus crisis, no amount of planning could have prepared them for what was to come. Ryan Wong had opened Needle in late 2019 in L.A.’s Silver Lake neighborhood, and it was being celebrated as a place for reimagined Hong Kong and Cantonese dishes. But then the disease started spreading in early 2020. “We were very cautious moving forward and made plans as to how to best proceed, buying time until the inevitable,” Wong says. “But we wanted to make sure we could take care of our staff in the meantime. Unfortunately, that time was cut shorter than anticipated.”

Food waste followed the losses in revenue, and although shelf-safe products could remain inside the building, all perishables were either donated or thrown out as the electricity and gas were shut off. Now, Needle is yet another restaurant with an uncertain future. “We’ve made efforts to raise awareness of the same circumstances occurring to other restaurants and small businesses across the country,” Wong says. “The hope is that the community will band together and that the government will provide some sort of support or relief.”

In New Jersey, Luck Sarabhayavanija, the owner of Ani Ramen, had to lay off more than 175 employees in order to stop bleeding money and to maintain the safety of his employees. “We took the information seriously from the beginning, but as the situation shifted and everyone was told social distancing was the best strategy, we anticipated the shutdowns and decided it was in the best interest of our customers and employees to close down altogether to prevent further spread,” Sarabhayavanija says.

Instead of shutting down all five Ani Ramen locations, Sarabhayavanija decided to launch two temporary nonprofit operations within the existing restaurants, offering pizza and Thai rotisserie chicken at discounted prices. They’re also providing food for first responders and victims of COVID-19. Even though they now stand threatened, small local eateries like Ani Ramen have helped to support countless events and organizations by supplying these meals. However, Sarabhayavanija adds that there has been one sad outcome in running an Asian American-owned enterprise. “Our sales decreased at double what our neighbors did because of the irrational fear of Asian food. People sometimes forget we are Asian American. But we have too much good left to do in our communities, so we don’t dwell on ignorance.”

Ani Ramen isn’t alone in its struggles. After the Lunar New Year, during a time when Chinese restaurant owners would typically see an increase of revenue, data from Eater shows there was actually a 20 percent drop in connections such as delivery and website clicks. Restaurants with a 100 percent decline in seated diners cannot survive, even with deliveries—costs of utilities and produce alone would be over the profit margins, unless that establishment was already built with delivery in mind, like food trucks or catering-centric restaurants.

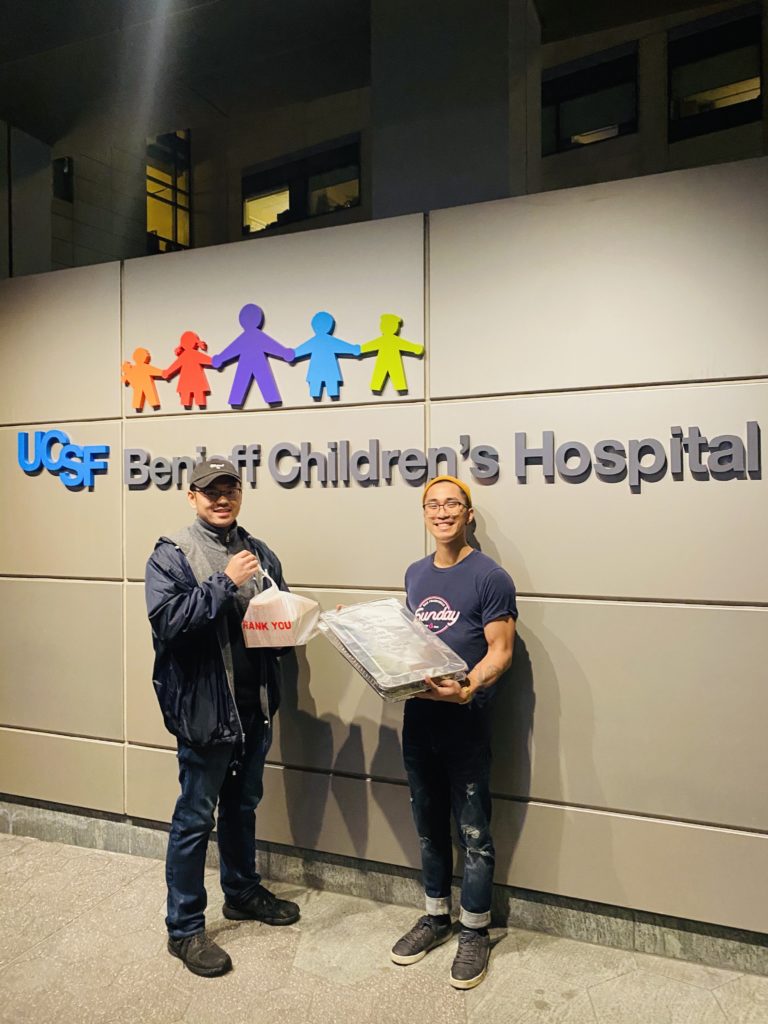

Deuki Hong, the mastermind behind the Sunday Family, a group of restaurants in San Francisco, explains that this new reality has caused an upheaval in his life. “That Sunday [March 15, after shut downs were ordered], I just woke up feeling weird,” Hong says. “I was at home processing and reflecting. I allowed myself to get as emotional as I needed to be, then come Monday, I decided to go to the kitchen and clean. I believe we will get through this, and I just wanted the chefs to come back to a beautiful, clean kitchen.”

Hong is still accepting catering orders to give his chefs some hours during the week. The sounds of a kitchen shuffling and a chef at work, giving instructions on cutting cabbage, can be heard over the phone. “We are shut down, but people are reaching out; if they couldn’t support us monetarily, they’d at least be able to place a catering order. The community so far has been great!” Hong says.

Still, Hong says his kitchens are mostly empty, so Sunday Family is among the thousands of restaurant groups to start GoFundMe pages for their employees to receive support while waiting for the government to take more financial action in support of now-jobless food industry workers. With donations exceeding initial expectations, Hong is excited to be able to provide for his team. But what has surprised Hong the most was the number of people sharing his story. “They’re getting the word out, and for me this is a privilege for the team because we just operate in our world, and we don’t know or realize the impact we may have on others,” he says.

Hong goes on to explain that he and his employees are using this time to rest, regroup and reorganize, in order to come back stronger. He also notes that the crisis has made him realize that serving people has been, in some ways, a privilege. “In this industry we weren’t supposed to be stopped, we were going to last forever,” says Hong. “[Even in] times of war, people have still wanted to go out to a dining establishment. It’s easy to take that for granted.”

Back at Tsai’s Blue Dragon in Boston, doors have closed for dine-in service, but the restaurant remains open for curbside pickups and to-go meals supported by the Let’s Empower Employment (LEE) Initiative for restaurant employees affected by COVID-19. But the restaurateur is already looking ahead to what business might be like when restaurants are finally able to go back to something resembling normal. For Tsai, the first challenge owners will face after isolation orders end will be reluctant customers who won’t have the means for a dining experience after having spent three or more months in an unemployed shutdown. “Feeding America is the most important thing; the domino effect will be so beneficial,” Tsai says. “We buy fish from fish purveyors, fruits and vegetables from farmers. So all these things just go down the chain. Everyone is hurting because no one is buying.”

Though the federal government has released stimulus checks to many, there’s an unacknowledged travesty in regard to the immigrants who have helped build America’s restaurant industry—undocumented workers who have not only lost their jobs, but are also left out of most stimulus packages.

That’s where Tsai’s passion to establish fundraising and charity for those affected by COVID-19 has bloomed. Tsai and others in the industry are working to generate emergency funds via campaigns such as the Restaurant Strong Fund and Family Reach to help stabilize families and individuals struggling during this crisis. “I do know that the only solution is to take care of your people,” Tsai says. As a first-generation Chinese American whose family immigrated for a better life, he understands firsthand exactly how much economic impact that immigrants have had. “Good things will happen to good people, be kind, be kind,” Tsai says. “We will get through this because there are enough people in this world who want to turn it around.”

He also points out that we can still do our part to help one another. “We need to be kinder to everyone, not just our family, but also our neighbors,” the restaurateur says. “We need to be kinder to people [who] have black skin or yellow skin, people who have a different way of speaking. We had to have a world disaster to realize how divisive the world has been against these people and each other.”

For Tsai, that kindness manifests itself through cooking and food. “You can do a lot with a can of tomatoes and a can of beans,” Tsai says. “Post it. Have fun or satisfaction because a bite of food is a great bite. You have to eat. Sometimes it’s a can of soup, but sometimes it can be a three bean souffle.”

Across the globe, Instagram users have shared posts on everything from their homemade bread and protein snacks to their one-pot wonders. We are all inevitably in this together, so why not show we care with food?

This article appeared in “Character Media”’s April/May 2020 issue. Check out our current e-magazine here.