Picture this: somewhere on the Atlantic coast, waves crash over a sandy beach while seagulls call and swoop through a cloudless, blue sky. Lounging on the sand with a friend, you find yourself lost in the pages of a classic Jane Austen novel, not a care in the world.

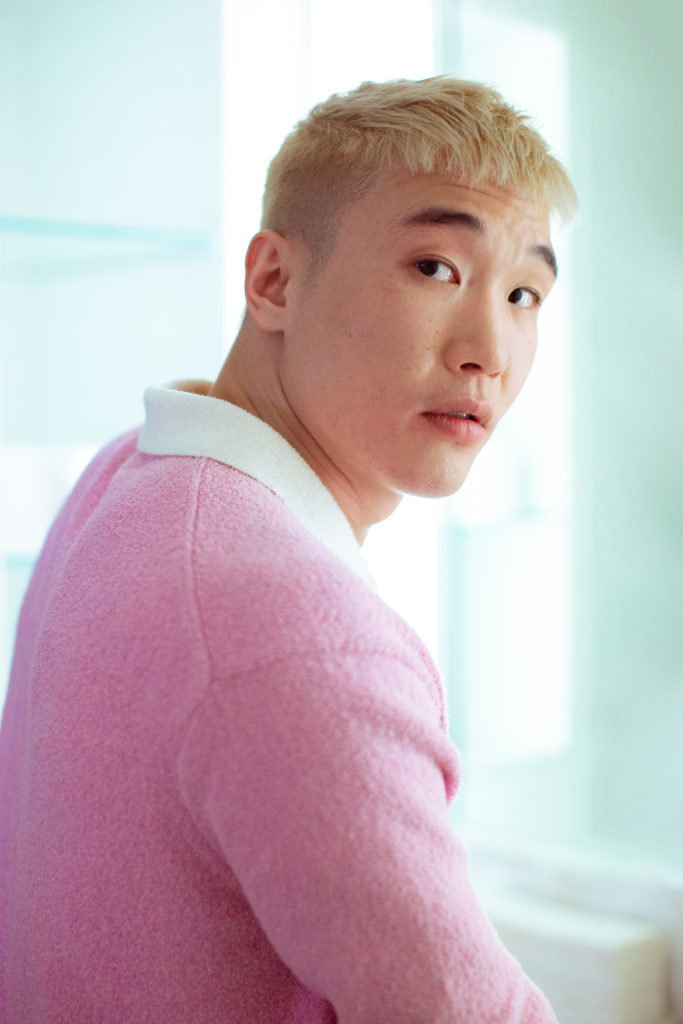

It may sound like a fictional meditation exercise, but a very real moment like this prompted comedian and actor Joel Kim Booster to write the gay romantic comedy “Fire Island.” “The genesis of the movie came from my first trip to Fire Island with Bowen [Yang],” Booster says. “I brought ‘Pride and Prejudice’ with me; it was going to be my beach read. And I kept being like, ‘Wow, everything [Austen] is talking about—the ways in which people communicate and fall in love across class lines—that is so relevant to what we’re experiencing on this island, with the artificial class lines gay men set up for themselves.’”

In those early conversations with Yang, Booster says he described the concept of the film as a joke and “a little bit as a threat.” But after its June 3 premiere this year, “Fire Island” has become an undeniable must-watch. Produced by Searchlight Pictures, the film follows Noah (Booster) and his found family of queer misfits during their annual—and possibly final—week-long vacation on New York’s famed isle, historically a haven for the LGBTQ community.

For those who have yet to watch the film, “Fire Island” is far from a by-the-book retelling of Austen’s classic. Noah wastes no time in denouncing the author’s opening lines (“A single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife,” etc.) as antiquated and heteronormative. But the novel’s timeless themes and characters have all been updated and brought to the screen by Booster and director Andrew Ahn.

A longtime friend of Booster’s, the “Spa Night” filmmaker jumped on board to direct after reading Booster’s script. “I really loved how much it focused on queer, Asian American friendship,” Ahn says. “Especially after a year through the pandemic, that was something I really missed—going out with friends, being stupid, dancing and drinking. So, I saw that in this movie and really wanted to bring it to life.”

Barring the occasional spat or voyeurism scare, Noah and his friends’ antics remain mostly fun and lighthearted. However, the larger significance of “Fire Island” is not lost on Ahn. “It’s hard to imagine that a film like this would have been made even five years ago, so I’m super happy to see it and I’m excited to see what continues,” Ahn says. “There’s always going to be obstacles whenever you make something about a smaller community. There’s systemic issues. But it was worth the difficulty because this is a really great opportunity.” Queer actors of color rarely get a chance like “Fire Island” to shine, but the film’s cast make the very most of the occasion.

Fittingly, “Saturday Night Live” comedian Yang also stars in the film as Booster’s on-screen best friend Howie, the cautious introvert to Booster’s brash Noah. Amid his more… well, horny friends on Fire Island, Howie exudes a palpable I-would-much-rather-be-at-home energy. But his avoidance of the island’s party scene and casual hookups has deeper roots: a fear of biases in the gay community, plus a genuine desire to find love and connection. “That developed organically,” Yang says. “Joel was responsible enough to introduce it to me on the page, but then we both massaged it. Howie is someone who externally adapts in order to be more accepted in this certain tier of gay culture. [We’re] mostly trying to grapple with these conflicting desires that everybody in the community contends with.”

While mainstream media often reduces gay male characters to interchangeable dispensers of fashion tips and catty one-liners, “Fire Island” brings some much-needed nuance. Because the film portrays dozens of gay characters, audiences get a peek into countless queer subcultures—even the ugly ones. “No fats, no femmes and no Asians,” Noah’s friend Keegan (Tomás Matos) says at one point, quoting a line often seen on gay dating app profiles. In a later scene, Noah faces off with a rice queen (a non-Asian man who exclusively chases Asian men), who simultaneously attempts to proposition Noah and guess his ethnicity.

To put it another way, “Fire Island” speaks to a little-acknowledged truth: The gay community is as diverse, and as rife with shallow prejudices, as any other demographic. And if the film’s protagonists do drop the occasional cutting quip or two, just know it comes from a place of love.

Like many viewers, actress and comedian Margaret Cho has waited a long time for LGBTQ representation to take this step. “We’re going into a queer story in a queer world, and therein lies so much complexity because you’re dealing with microaggressions to being queer and Asian American,” Cho says. She plays the unofficial den mother, Erin, to Noah and Howie’s found family. “There’s so much we need to discuss in terms of being a minority within a minority community, so there’s a lot that has never been brought up in film before that is really rich, unique and exciting to watch.”

“Fire Island” has to toe a fine line, acknowledging the hardships of queer, Asian American existence without allowing them to define the characters. Luckily for viewers, Ahn and the film’s cast find that balance with a good sense of humor. Take it from Conrad Ricamora. He plays the Mr. Darcy-esque Will, a withdrawn lawyer who initially clashes with Noah and his friends but later warms to their oddball group. “The movie shows what happens to us all the time because we are gay Asian men,” says Ricamora. “I like that [‘Fire Island’] lets us laugh about it, but also doesn’t get us stuck in the trauma aspect. It shows the difficulties we face and allows us to be empowered and own our narrative.”

The strategy may sound especially familiar to queer viewers. Yang explains that it stems from real, lived experiences. “On set, we had a shorthand that a lot of queer people have, which is to be very vulnerable with our hardships and experience, but also to not wallow in it too long,” he says.

For better or worse, “Fire Island” is novel in this regard. Upbeat portrayals of the queer adult experience, sans identity crises, heartbreak and dramatic coming-out stories, have long been missing from most cinema (no offense to “Moonlight” or “Happy Together“). “We have been narratively conditioned into our own suffering, and the beauty of queerness is that you overcome a lot of that,” Yang says. “These [characters] are not existing in opposition to anything that normative society dictates; they’re just existing as adults with realized aspects of themselves. It’s really refreshing.”

The cast and Ahn hope to inspire more queer Asian Americans to share their stories. But moreover, Ahn wants to foster connections that go beyond the screen. “My hope is that audiences watch the film and really value their friendships,” Ahn says. “There’s so much value to our community. It’s too scary to navigate this world alone, and so that’s my big hope, is that it brings groups together.”

Booster notes that the film has an added significance for older LGBTQ generations. “We don’t get a lot of stories that are for us,” Booster says. “This movie was about showcasing pure joy and how transformative it can be to have a chosen family assembled around you. I want people to walk away happy they’re gay because we don’t get a lot of movies like that.”

And there’s no better place to start than the iconic Fire Island. “That island means so much to so many people, and it means different things to different members of our community,” Booster says. “There’s a lot of pressure in having one of the first movies to center the island in a big way. I was really nervous about doing it, but ultimately, I really love that place.”

If anything, Booster, Ahn and the rest of their crew have created an even better Fire Island—a space that welcomes everyone, where the sun almost always shines.

This article appeared in Character Media’s Annual 2022 Issue.

Read our full e-magazine here.