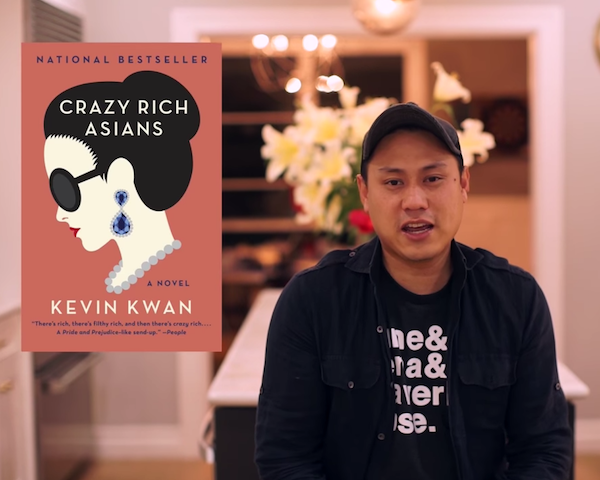

“Crazy Rich Asians” — the big-screen adaptation of Kevin Kwan’s 2013 novel of the same name — is not just a gorgeous movie with the color and energy of an MGM 1950s musical. It’s not just a modern-day class-war romp with a heroine and villain worthy of a Jane Austen novel (respectively, Constance Wu as Rachel Chu and Michelle Yeoh as Eleanor Young).

But really, why is this film such a big deal? Weren’t we promised in the past that Asian-led film vehicles like “The Joy Luck Club” would pave the way to a million more Asian-led films being greenlit only for that to never materialize? Why should “Crazy Rich Asians” be different? A number of reasons.

Non-whites, kissing

In 1986, the year of Spike Lee’s big breakout film “She’s Gotta Have It,” the then-neophyte director asked the New York Times, “How often have you seen a black man and woman kiss on the screen?” The answer: Never. Neither black nor non-black audiences had seen such a thing.

If that seemed implausible in 1986, it seems even more implausible 32 years later that the same could be said for Asians in Hollywood. As prominent thought leader Jeff Yang said in an episode of “They Call Us Bruce” (the entertaining podcast he co-hosts with “Angry Asian Man” Phil Yu), “The romantic comedy genre is the whitest genre in Hollywood.”

The Observer Effect

This quantum physics concept states that all entities behave differently if they are being observed, because the observing party always imputes influence on the object of observation, be it intentional or not. Nowhere is this clearer than the way the dominant culture of any given society views a non-dominant culture. With any film focusing on Asians in the West, the West part always gets in the way. Asian American cinema, while vitally important, is always about how Asians function in a particular Western petri dish.

By contrast, “Crazy Rich Asians” takes place almost entirely in Singapore — outside the Western gaze — and thus gives insight into how Asians behave when they’re just…people. Issues like class, generations, cat fights, and in-laws get pulled into sharp focus, making this story a comedy of manners in the purest form — not a comedy of race and manners.

The implied significance of yellow plastic cases

It’s true that streaming services like Amazon Prime Video, Netflix and Hulu are giving traditional Hollywood studios a run for their money, even taking over the Emmys and Golden Globes. Yet theatrical releases still matter. Kwan said in the Hollywood Reporter that he and director Jon M. Chu turned down a “chance for this gigantic payday” from Netflix, instead choosing to have the film distributed by a mainstream, “traditional” studio, the 95-year-old behemoth Warner Bros.

Brick-and-mortar cinema distribution matters for the same reason that writers are way more excited to get a book in print than as an e-book: The pure physical logistics involved in distributing a feature film to movie theaters is a testament to the faith that the financial backers have in the film. Actual planes fly actual yellow plastic cases containing actual hard drives that store the movie. A kid comes in after school to scan your ticket QR code. An entire ecosystem of workers and resources come together for a movie to be shown at a brick-and-mortar theater. It takes a village, so to speak. And in the case of “Crazy Rich Asians,” that whole village is working in the momentary employ of a film that stars Asians.

Rich, but over there

Now for a bit of caution: We shouldn’t be betting that this one film will change the way Western moviegoing audiences think of Asians. Let us not forget that the Crazy Rich Asians of the title refer to diasporic Chinese in Asia, this almost mythic race of wealthy Han Chinese merchants who all but run Southeast Asia.

Their wealth is fabulous, but it is also far away — at least from the Western POV. What’s unclear is whether mainstream Hollywood audiences would be as delighted by the sight of seeing these types of stories amongst Asian Americans. What if the storybook wedding were to take place not in Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay, but the United Methodist Church of Grosse Pointe, Michigan? What if the characters continued to act as if they were the dominant culture, but in a country where they are a vast minority?

In 2016, New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis devised criteria for measuring diversity in a given film, which she called the “DuVernay Test.” Per the “test” — named for the groundbreaking African American director Ava DuVernay — a truly diverse film is not one that features a large number of minorities, but rather one “in which African Americans and other minorities have fully realized lives rather than serve as scenery in white stories.” Hollywood films featuring Asian Americans have been lagging behind by DuVernay Test standards. Were that to be overcome, that would be the true victory. I look forward to a project like “Crazy Rich Asians Part 17: Rachel and Nick’s Kids Choose Between Scarsdale High and Horace Mann.”

Euny Hong (@euny) is a journalist and author, most recently of “The Birth of Korean Cool: How One Nation Is Conquering the World Through Pop Culture.” Her work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, the Times of London, and elsewhere.