A journalist incarcerated in China for almost four months says he still has no regrets about his risky work reporting news about North Korea.

by JOHN CHA

illustration by INKI CHO

THE LAST THING Lee Sang-yong wanted to do in his life was to spend 114 days in jail. A Chinese jail, no less. He was ready to head home to Seoul on March 29, 2012, following a three-year stint as a correspondent for an Internet newspaper, the Daily NK, when Chinese intelligence agents nabbed him in Dalian, a port city at the tip of Tsingtao peninsula, about 200 miles west of Dandong.

“I’d just gotten off the bus from Dandong on my way to see my colleagues there. Four plain clothes men came up to me and handcuffed me, my hands behind my back,” Lee, 28, described, during an interview in Seoul. “The handcuffs were so tight. It hurt so bad, I couldn’t think of anything else.”

He had no idea what the gruff Chinese intelligence agents wanted and wondered if they had made a mistake in identity. He would later find out that they knew exactly who he was and that he was a journalist from South Korea. They drove him back to Dandong and put him in a small cell with 20 or so people in it. It was so crowded, he had to sleep sitting up. For meals he was given a Chinese bun and a bowl of clear broth three times a day.

The first day in jail, they told him nothing. The second day, when he was called into an interrogation room, the agents started by saying, “You should be thankful that we saved you from the North Korean agents. We found out that they were following you around. We got seven of you guys yesterday.”

Lee was grimly amused. They had a strange way of showing their concern for him, he thought—handcuffing him and throwing him into a crowded cell. Yet, he was not worried at this point because the usual M.O. for the Chinese authorities had been to deport journalists like him after a day or two.

Two days went by, and by the third day, they did an unusual thing. They took him out of the holding tank and transferred him to a regular prison. They hadn’t charged him yet, and he didn’t know what was going on until he got a glimpse of his data sheet on the computer screen during the registrationprocess. His sheet said, “Crimes against national security,” confusing him to no end.

One week, and then two weeks went by, and the agents didn’t show any signs of letting him go. The prison was an improvement over the holding cell. He didn’t have to sleep sitting up anymore, and there were two toilets in the barracks he shared with 20 inmates. He wanted so badly to brush his teeth and take a shower, but no such luck, though he was allowed to wash his hair after 20 days. He could have bought chicken and pastries from the prison guards, but that was out of the question since he didn’t have any money.

He went over and over in his mind what he had done during the past three years that they could have construed as “crimes against national security.” The Chinese agents knew what he did in the greatest of detail, especially after they confiscated his Nikon camera and his computer containing the stories he had filed to the Daily NK headquarters in Seoul. Lee thought they should have known that he had done nothing to compromise the national security of China, but there he was, locked up in a cell that reeked of a chicken coop.

Photo by John Cha

About a month into his incarceration, an interrogator told him, “Normally, we’d notify your family after one day, but in your case, no dice. Instead, we’re going to send you to North Korea, so they can tie you up to the rocket they’re going to blast off.” They seemed to enjoy threatening him like this, Lee thought.

The threats got to him. He became tense and nervous as time went on and developed post traumatic stress disorder, breaking out in hives all over his body. His mission as a correspondent had been to collect and report news stories from North Korea for the Daily NK, a news organization closely followed by many North Korea experts. Its founders had mortgaged their homes in 2005 to start the nonprofit news organization that went on to break major stories, such as public executions, botched currency reform in North Korea, the severe food shortage and purges of government officials. Stories are published primarily in Korean, but also in English, Chinese and Japanese. The Daily NK is often cited as a news source for many international news organizations including the New York Times, Washington Post, BBC and the Asahi Shimbun.

Though the paper’s founders are clearly opponents of the North Korean regime and its reliability has sometimes come into question in the past, with the South Korean Ministry of Unification once saying its “flood of raw, unconfirmed reports” was unconstructive, the New York Times wrote that, since 2010, the accuracy and quality of news published by the Daily NK had improved. Even Kim Jong-nam, Kim Jong-il’s first son, was once quoted as saying in a Japanese newspaper that “the Daily NK is accurate about North Korean markets,” although he had reservations about its reports about the party elites.

Over the years the online newspaper quickly become a thorn in the eyes of the North Korean authorities. In fact, the hardliners in Pyongyang continually threatened to bomb its Seoul office to smithereens, calling it the “enemy of the republic” and “imperial dogs,” the usual epithets reserved for those they consider hostile.

Lee was aware of these threats and of the presence of North Korean agents who roam the border region in search of the “betrayers of the republic,” which include North Korean defectors, missionaries and journalists. Thus Lee carefully planned his movements to avoid surveillance, alternating buses and cabs wherever he went. Upon reaching his destination, he’d find a high point to scan the area to make sure that he was not followed. If he wasn’t sure, he’d break off the meeting and make a new arrangement for another day.

“I never knew if my contact was going to show up or not,” said Lee. “Sometimes it would take three or more attempts before we finally meet up, and sometimes, we would never get to meet. I interviewed hundreds of defectors this way. The hardest part about my job was arranging and meeting informants and verifying stories. I had to interview multiple sources to doublecheck stories about what’s going on in market places around North Korea or on the streets of Pyongyang.”

Real news about North Korean people is hard to come by—other than what the party’s propaganda department prints or broadcasts. Nevertheless, Lee had become accustomed to the world where surreptitious news gathering is the norm, constantly mindful of the North Korean agents who watch informants and journalists alike.

Lee attributes this condition to Kim Jong-il’s “fog veil” strategy, with respect to the outflow of information—any information. Kim once had fallen off a horse, which required hospitalization. He was not seen for months, and no one, other than an immediate few, knew about his fall. Not even the party cadre of the central committee.

More than three months after his arrest, Lee noticed one day that a prison guard had added kimchi to his usual meal of mantou and clear broth. His fellow inmates told him that the bonus was a sign of his imminent release. He was released two weeks later, on July 20, with an order never to return to China.

It wasn’t until he landed at Incheon airport that he learned about a concerted international campaign to free him, as well as other Korean journalists who had also been arrested. He is not certain why they released him, but reflects, “I think [the Chinese authorities] got tired of dealing with all the pressure and criticisms about their record on human rights. I get the feeling that they wanted to make an example out of [me] with a clear message to stay out, even though they said they saved [me] from North Korean agents.”

Despite his incarceration, Lee said he remains committed to telling stories about North Korea. “I feel the happiest when I run into readers who say that they are learning about North Korean society,” he said. “I also met some North Korean officials, they didn’t know who I was, and they told me that the Daily NK was really a terrible site. I laughed inside and felt proud that we’re doing a good job.”

An electronics engineering major who graduated with honors, Lee could have pursued a much more lucrative career working at a major high-tech company, rather than at a news organization that is hard-pressed to make payroll every month for 25 reporters, translators and administrative staff. Asked about his choice for a life of poverty, he smiled and said, “I am the youngest of the eight children in my family, and my sisters and brothers are concerned about that. But where else am I going to find this kind of camaraderie? I am very happy working here.”

Funding was a major problem during his tour in Manchuria, and it still is for other correspondents. “I lost many contacts and stories because I didn’t have the money to pay for their meals and cab fare,” Lee lamented. “I skimped on meals and lived in cheap rooms to save what little money I had for my informants. My life was definitely below poverty level. We do need financial help.”

Nevertheless, the journalist is not discouraged from wanting to go back to Manchuria. He hopes to return someday and write stories about life in North Korea, provided that the Chinese government lifts its ban on his return. He would like to get his camera back, too, but he is not counting on it.

I told him about writer Jack London’s confiscated camera in 1904, when he went to Korea as a correspondent for the San Francisco Examiner to cover the Russo-Japanese War. London finally recovered his camera from a Japanese army commander with the help of the U.S. State Department. Lee replied, “My camera is gone, my computer and my note pads. They told me they would burn all my belongings because they were used for an illegal purpose.”

Despite a painful almost four months in prison, Lee is very philosophical about his experience. It took him three months to fully recover from his stress disorder, and he is now back at his desk, as committed and feisty as ever. He said he feels energized by the friends he made back in Manchuria over the past three years.

“I have no regrets, only that I feel like I’ve let down my fellow journalists [by getting caught]. I have to redeem myself now.”

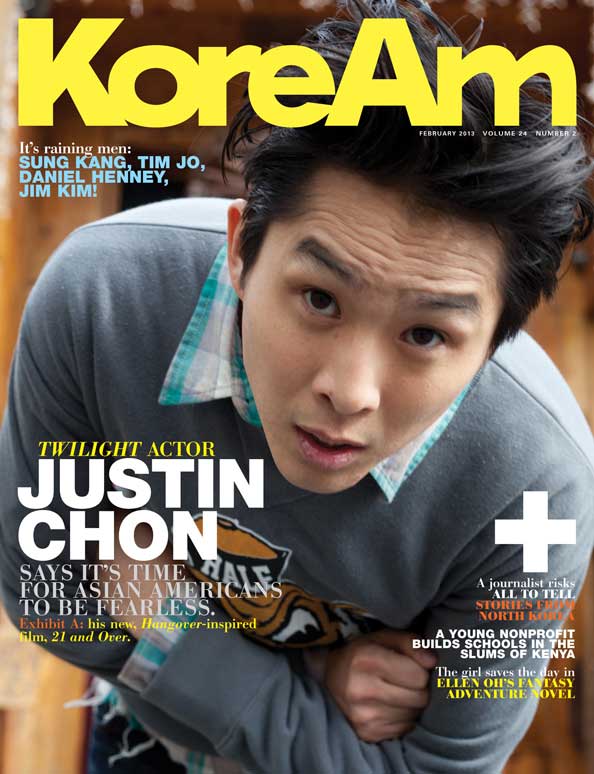

This article was published in the February 2013 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the February issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only.)