“Do you think you are talented?”

The query, directed at rapper Dumbfoundead, hangs in the air, frozen like a waiting high-five.

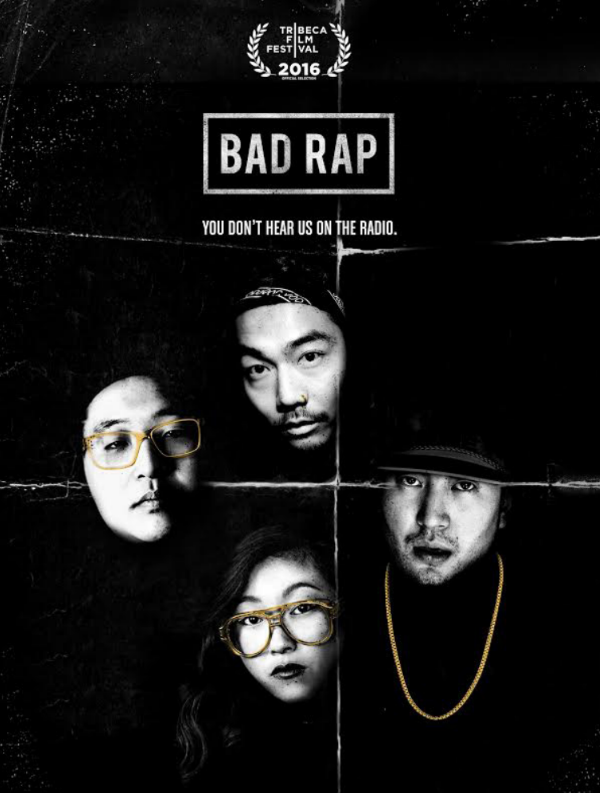

Four rappers are the subject of director Salima Koroma’s documentary feature, “Bad Rap.” They are all Asian American, lumped together by the intersection of craft and hyphenated singularity, but they couldn’t be more different.

Rekstizzy, aka David Lee, hails from Queens, New York, and flies on a different wavelength but in an immediately likable way.

Lyricks, aka Richard Lee, is grounded by faith and a close-knit family, and has been doing hip-hop since his teens.

Awkwafina, aka Nora Lum, is a rapper well-known for the viral hit “My Vag,” and her lyrics and style make one hard-pressed to find her comparable to anyone else.

Dumbfoundead, a.k.a. Jonathan Park (a.k.a. “Parker”), spent his adolescence slipping in and out of battle rap parties in Los Angeles (where he was the only Asian American at the jawn), and developed a formidable skill set as a masterful improviser.

The film takes a behind-the-scenes portrait of a world likely few have seen unless in-the-know. It illustrates these artists in their element, performing at concerts where they sometimes share a lineup, and offstage, in more personal moments with their families.

Though at various stages in their careers, each have ambition and bravado, a considerable following, the strength of social channels and technology and each other, a worldly perspective on the music industry, and an even sharper lens on branding, marketing, hip-hop, and their place in it.

But what the documentary investigates is not the nature of their talent, but the obstacles standing in their way: Why aren’t these four rappers more successful?

The film chronicles the current state of affairs, the seminal obstacles stemming from Hollywood media’s historically limiting constructs of Asians to mere caricatures and one-dimensional, globally pervasive stereotypes, and working in a genre dominated by African American talent.

There was little for these artists to witness as a crowning example of what they could be during their formative years, with few Asian Americans – or Asians, even, in the spotlight. Except for the few depictions of Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Margaret Cho among the sea of hypersexualized Asian females and emasculated Asian males, this was an era where there was no Eddie Huang, no Mindy Kaling, no Jeremy Lin, no Alan Yang. Our hip-hop squad of concern recognizes that the fact that they exist as rappers alone is a triumph in itself, especially for the kids in America that for so long had no voice and no representation, because they were once one of them.

But while some may argue that it is enough to simply be present, others may not be satisfied until a breakout star, an Asian American rapper, rises as a game changer – an artist with a legacy no one can deny. Perhaps one of the film’s subjects may emerge to carry the torch. Did anyone really respect white rappers until Eminem?

A who’s who of Asian American media and music personalities weigh in, with appearances from Far East Movement, the Fung Brothers, Kero One, Traphik, Jay Park and Danny Chung. Early music videos of our artists’ predecessors like the Mountain Brothers and MC Jin stand not only as artistic pioneers and cultural influences, but milestones.

Industry execs review our hip hop artists, completely unknown to some while others are solidly familiar; in other moments the suits struggle to name any Asian American rappers.

Our four documentary subjects ascertain what the future holds for them and their fellow colleagues: these are four very distinct artists with unique styles, personalities, and upbringing all laid out in their music. It’s interesting that they are all sharply perceptive of how the world sees them; they’re self aware and sensitive to the playing field and the challenges that lie here and ahead, and how they fit into and don’t fit into, the music industry as a whole. But the industry is no longer as concrete as it once was.

This digital age comes with the freedom where they can interact with fans directly and build a following without a major label, booking agent, and obligatory industry entourage to ensure a machine of success.

Whether intentional or not, the film chronicles the sacred hustle.

And while putting media stereotypes and industry aside for a moment, our artists reveal that the biggest obstacle standing in your way might just be you.

Dumbfoundead’s mother beams with her son’s success but also recognizes some of his demons to creativity.

Lyricks is conflicted between his true passion as a rapper and his identity as a man of faith; though he desires the gifts that come with acknowledgment in the industry, perhaps what he anticipates most is the recognition from two of his fans: his parents.

Awkwafina sees less certainty in her future compared to her colleagues, while they see her rapidly expanding portfolio of opportunities as understandable but stupefying.

Some highlights of the film include:

–Rekstizzy defending his artistic vision of squirting condiments on the derrieres of African American models in his music video.

–Dumbfoundead going toe-to-toe with Conceited in battle rap, a brilliant storm of talent facing off in a charged verbal combat which does not disappoint.

–While Drake expresses a genuine admiration and recognition for Dumbfoundead’s work and talent, reporters at the same press conference made jabs at his ethnicity with archaic and racially insensitive jokes.

82 minutes. Documentary feature. Directed/produced by Salima Koroma, produced by Jaeki Cho.

Watch the “Bad Rap” trailer: