One of my first introductions to Hawaiian food—in Hawaii—came at a gas station. It was on my first trip to the island of Kauai, and friends swore that I could find some of the best Spam musubi at a service stop along the north shore. I was a bit skeptical—mainland gas stations are not exactly known for their gastronomic excellence. But I stopped by, and there on the counter was a neat stack of cellophane-wrapped musubi: Thick slabs of grilled Spam sitting atop firm bricks of rice, wrapped with strips of dried nori. I didn’t grow up eating Spam and always assumed the worst, but then I realized, what’s not to like about salty, fatty meat portioned into a convenient, portable snack?

Whether Spam musubi originated in Hawaii is up for debate; Japanese Americans in both California and Hawaii claim to have invented it during the World War II era. Origins aside, the dish has become synonymous with Hawaiian foodways, and with roots in both Japanese culinary traditions (musubi) and the American military (Spam), the dish is one of many that encapsulates the islands’ long, complicated history.

On one hand, it’s tempting to think of Hawaiian food as a kind of ur-fusion cuisine. Long before “fusion” became associated with cheesy 1980s restaurant concepts, the islands’ polyglot mix of native Hawaiians and successive waves of Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean and other Pacific Islander migrants helped meld together food traditions to produce dishes as blended as the region’s pidgin dialect.

Having said that, I don’t want to be too glib here. There’s a tendency for Asian Americans on the mainland to view Hawaii as a kind of ethnic paradise, especially as the only majority-Asian state in the union. However, Polynesians arrived on the islands almost two thousand years before the first Asian migrants came ashore. The primacy of Asian Americans in local political and economic society is a sharp contrast to the historical marginalization of native Hawaiians. Just because the descendants of both indigenous Hawaiians and Asian immigrants share space there now, they don’t always do so equally.

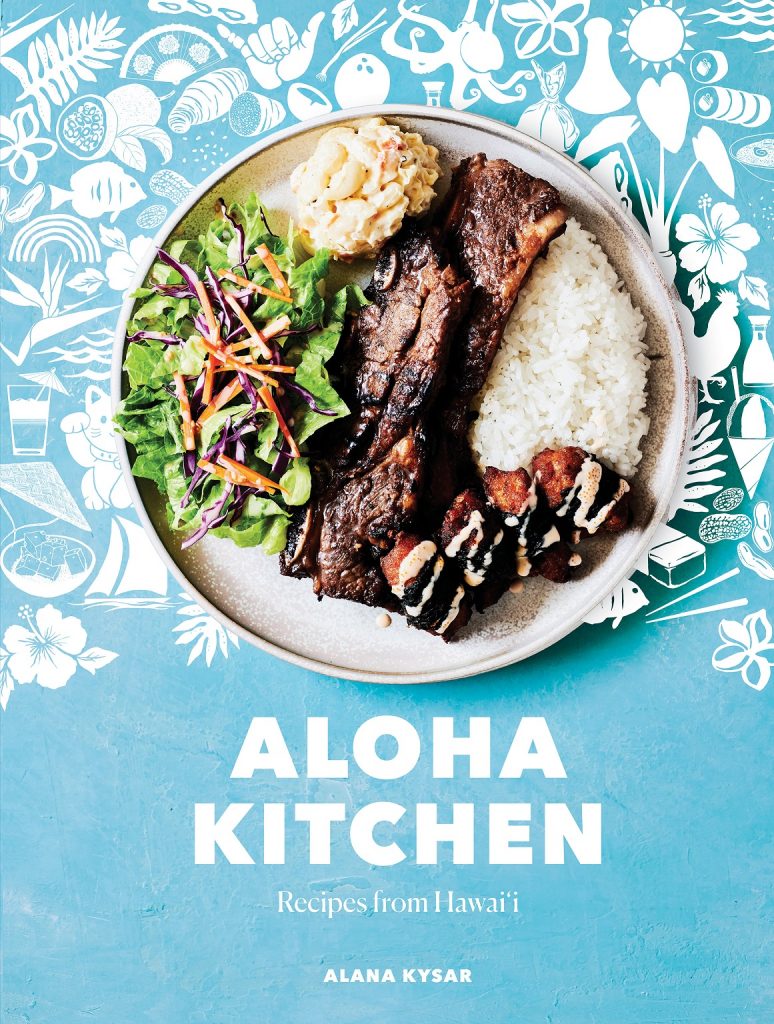

In Alana Kysar’s new cookbook, “Aloha Kitchen,” she doesn’t directly discuss the state’s thorny ethnic politics. But she acknowledges that, even as a fourth-generation Japanese American from Hawaii, “only people that are ethnically Hawaiian are considered Hawaiian,” which speaks to the islands’ particular identity dynamics. Kysar is attuned to this history and includes a six-page guide to the ethnic and political background of Hawaii, beginning with Polynesian wayfinders between A.D. 300 and 500, through waves of Asian plantation workers between the mid-19th and early-20th centuries, and ending with a condensed timeline of Hawaii’s path from sovereign monarchy to American annexation and eventual statehood. There’s much to take in here, particularly for a cookbook, but “Aloha Kitchen” is rooted in the idea that “local Hawai’i food is a direct result of Hawai’i’s past and continues to be a living, breathing expression of what Hawai’i is today.” For Kysar, who began writing about food as part of her popular “Fix Feast Flair” blog, even something as humble as the plate lunch can bring together what she describes as “this beautiful, delicious amalgamation of Hawai’i’s migration history.”

“Aloha Kitchen” is a primer-style cookbook, including recipes for classic dishes that now populate both mainland “Hawaiian BBQ” eateries, as well as family-style restaurants on the islands themselves. That includes lomi salmon, with its mix of tiny diced pieces of fish, tomato and Maui onion. There’s pork laulau: small, fist-sized chunks of pork shoulder wrapped in bright green taro leaves and slow roasted until fork-tender. And of course, there’s the delightfully named loco moco, made with thick patties of hamburger meat spiced with Worcestershire sauce and best served with a thick gravy, a crisp-edged fried egg, a side of mayo macaroni and two scoops—it should be two—of rice to soak up all that richness.

I started with Kysar’s shoyu ahi poke. This dish, originally made from discarded fish scraps, was once unknown outside of Hawaiian supermarkets and speciality stands, but the last 10 years has brought a wave of poke eateries to the mainland, contributing to an epidemic of both overfishing and terrible punny restaurant names. It’s easy to see the appeal, though. Kysar’s recipe takes the silken feel and natural sweetness of fresh tuna and marries it with a winning combination of soy sauce’s savoriness, the toasted richness of sesame oil, a kiss of sugar and a pinch of Korean gochugaru chile powder for some color and mild spiciness. When tossed with slivers of sweet Maui onion and chopped scallions, this simple poke recipe upgrades what used to be fish scraps into something more sublime, thanks to its contrasting flavors and textures.

Next, I made her “local-style BBQ chicken” recipe—a riff on the huli huli chicken found across the various islands, mostly roasted in roadside pits over open coals. It shares much in common with Japanese American-style teriyaki, though its incorporation of ketchup ups the umami while the added sugar abets the caramelization process once the chicken hits the grill. Kysar’s recipe calls for boneless, skinless chicken thighs, but I think these would work just as well, if not better, with wings, especially with a hot sauce glaze at the very end.

Having spent last summer cooking Filipino dishes, I was curious to try Kysar’s take on pork adobo. Her approach uses similar ingredients as most recipes: bay leaves, peppercorns and, of course, cane vinegar. But Kysar diverts from tradition by adding a key ingredient: half a bottle of lager beer. It creates a subtle new dimension rather than anything dramatic, but at the very least, it’s a reminder that adobo merely provides a basic canvas that cooks can play with in many different ways. Besides, given the long cook time an adobo braise requires, having that other half of beer to quaff helps pass the time.

With over 80 recipes, I’ve barely skimmed the surface. And though I’m eager to try out everything from Kysar’s smoky kalua pork to the ginger misoyaki butterfish recipes, I was distracted by her long list of sweets and snacks in the book’s last third. That includes everything from a decadent-looking double-chocolate haupia pie to sugar-rolled Portuguese malasadas to baked taro and sweet potato chips. I’m especially curious to try out hurricane popcorn, which takes savory furikake powder and a handful of mochi crackers and adds them to buttered popcorn for an island take on Cracker Jack.

Even if “Aloha Kitchen” is meant to be a starter’s guide to Hawaiian classics, reading it opened up a natural curiosity to see what new dishes are being crafted in the islands now. As much as the food is rooted in traditions brought over by countless generations of newcomers, those waves have constantly reshaped the islands’ foodways. Hawaiian cuisine can feel both ancient and modern as a result. And if the aloha spirit continually beckons others to traverse sky and ocean to arrive there, the food will still continue to evolve.

This article appeared in Character Media’s May 2019 issue. Subscribe here.