There’s more to “Kimchi” than meets the eye. At first glance, it appears to be a story about an elderly man meeting his granddaughter’s fiancée. Upon closer look, however, its lead characters, played by Ken Takemoto and Yuki Matsuzaki, connect despite multiple barriers: generational, cultural, linguistic, and historical. The short film, which premiered last month at SXSW, is in English, Korean and Japanese.

Director Jackson Kiyoshi Segars discusses funeral photos, the lack of Asian American films, and the difficulties of casting for a film told in three languages.

Tell us about your film “Kimchi.”

“Kimchi” follows a day in the life of a Korean family, and the granddaughter brings her Japanese American boyfriend over in the midst of a health crisis for the grandfather. In the end, it’s about a man taking another man’s photo and trying to get him to smile.

How did the story come about?

The story was inspired by a trip I took to Korea several years ago with my fiancée. It was inspired by going to her grandparents’ home and seeing this peculiar photo on the wall and being curious about the origin of that photo. As I was visiting her family, I couldn’t really communicate with anyone. Most of them couldn’t speak English, and I don’t speak a lick of Korean. But I was able to have a very brief conversation with her grandfather in Japanese. I speak Japanese very poorly. But this idea of being able to communicate, sort of bridging the cultural barriers and language barriers and just finding the connection through those barriers.

When writing the script, my grandfather and my fiancée’s grandfather were both struggling with dementia and Alzheimer’s, respectively, so I was thinking a lot about the importance of memory and symbols in constructing identity and deriving purpose from life.

When you mention the photo you saw on the wall, was that a funeral photo?

It was a photo of her grandfather who actually passed away later that year, or maybe a bit after that. I was compelled because I grew up with a similar photo of my Japanese grandfather on our wall, but that was commemorating his passing. I was surprised that it looked very familiar, similar to that photo, but her grandfather was still living at the time.

Do you find that depressing?

Oh, no. Just curious, not necessarily depressing. Maybe even a bit more honest, living with this confrontation of a future relic of your own death, maybe it’s a little bit brave.

(Courtesy photo)

What age is the grandfather character in the film?

The grandfather was born around the early 1930s, having lived through Japanese colonialism in South Korea. A lot of Koreans were educated by the Japanese during the colonization and forced to learn Japanese. And that was the case with my girlfriend’s grandfather as well, that’s why he was able to speak Japanese and why we were able to communicate.

The characters in your film spoke Korean, English, and Japanese.

The requirements for these actors and these characters to be of a certain age, a certain ethnicity, language requirements, really narrowed down the talent pool of who I could actually cast.

I spent several months scouting in New York and New Jersey, going to these Korean and Japanese seniors’ organizations and cultural centers. Tried to do some real people casting. I don’t speak Korean and I’m not fluent in Japanese, so it’s really difficult to communicate with these communities, since a lot of them were not bilingual. So I was really reliant on translators or interpreters in the process.

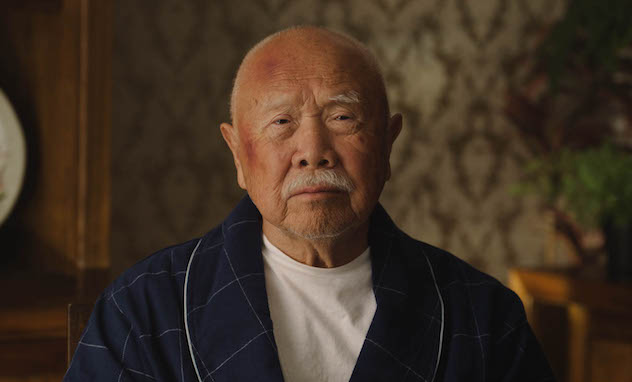

Ken Takemoto, who plays the grandfather, is not fluent in Japanese so we did a lot of phonetic coaching with him to get the pronunciation right. And I always had Jennifer Kim, who plays the granddaughter, in mind. I had seen her work in the past. Yuki Matsuzaki, who plays the fiancé, was someone I had researched through IMDb.

Where was your shooting location?

Harlem. It was actually at my fiancée’s parents’ home. We had a different location picked out initially, but due to the vicissitudes of filmmaking, we lost it about three weeks before the shoot date and had to scramble to find a new location.

It looked great, though, especially the production design.

Maybe the location change was a blessing in disguise. It was a pretty low budget film, so you’re working with what you have. Given the circumstances, my production designer Henriette [Vittadini] did a really good job, repurposing things in the house.

(Courtesy photo)

There’s a lot of historical elements in your film. The lead character grew up during Japanese occupation, war, the Name Order in 1939 — there’s so much that this character has lived through. When he started speaking in Japanese, I couldn’t help but imagine what it took for him to make the conscious decision to do so, despite any lingering resentment or embittered feelings he may have had.

The grandfather’s at a certain age that his dementia also affects his demeanor. He’s relinquished a lot of those grudges. Initially I conceived that he was reconnecting with a language that he hasn’t used in a long time. I think that language can really activate certain parts of our personalities.

The element of historical traces of colonialism was never something I intended to emphasize, using it more as exposition. It’s an opportunity use language to communicate with someone who’s going to be a part of his family.

What was the biggest obstacle in making this film?

I would say it was the casting. For these particular roles, for such specific characters, it proved very difficult. Presented with this paradox of trying to cast Asian American films, which is, you need the actors to make your movie, but it’s hard to find a large repository of Asian American actors, because not many Asian American films are being made.

What’s next for you?

I have a couple kernels of ideas I’ve been writing recently. I’m working with my production company, Video Horse. We do a lot of branded content and commercial content. But we also create our own projects and short films. So hopefully I’ll be back in the director’s chair again soon.

Follow the film online at kimchifilm.com and the filmmaker @videohorsefilms or videohorsefilms.com.