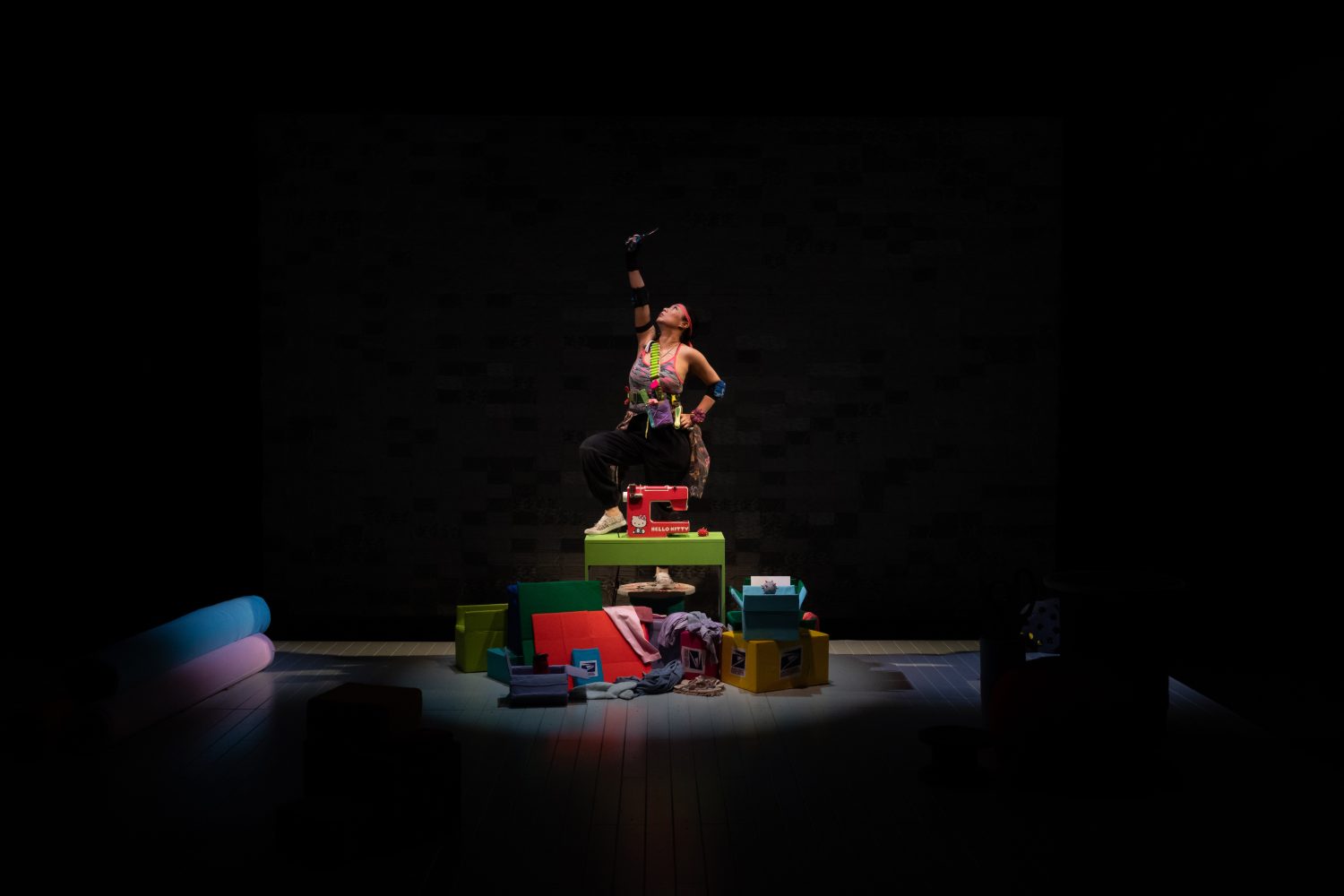

“Is America a Banana Republic?” Performance artist Kristina Wong poses this question to her audience multiple times, decked out in a pink and gray camo tank top and a tactical shoulder sash lined with, not weapons of mass destruction, but clothing pins, needles and spools of thread. Is America’s chain of command in crisis as inept as the fast fashion corporation is… generally? During “Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord,” Wong guides her audience towards the answer. In the show, she documents the rise and fall of her pandemic-initiated grassroots coalition “Auntie Sewing Squad,” a Facebook group dedicated to sewing masks for marginalized groups during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Wong got her start in live theater in 2006 with “Wong Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” — a one-woman show about the prevalence of mental illness among Asian American women. Now, in 2023, she is a Pulitzer Prize finalist in drama, and her projects are underlined by her commitment to amplifying underrepresented stories. This is where “Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord” began.

CM: How long did it take you to create “Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord?” How did the idea of performing a show about your sewing group even come to fruition?

Wong: I saw an article that hospitals needed homesewn masks, [and] I started sewing masks. It’s not like I’m sitting on a plethora of cotton fabric and elastic. The first ten days of this was so frantic — running around trying to get materials. My friends were like, ‘This is gonna be your next show.’ And I said, ‘No one wants to relive this. Do you want to relive this?’

I started the “Auntie Sewing Squad” four days [into the pandemic] because I needed to help. It was supposed to be a casual stopgap. How is it that me, a non-essential performer, is something of the difference between life or death? Why am I fielding calls from health professionals who are scared to go to work? That’s when it became clear I was seeing something that needed to be recorded. About a month in, I created a piece on Zoom. It was in my house, and you would just see day fourteen, day six, day thirty-three — that’s how I developed it.

CM: So, the show was building on itself throughout the pandemic.

Wong: I’m glad I wrote it down. A lot of the reactions I get [are], ‘I forgot so much of that!’ All these little memories come up for people.

As a sewing group, we felt every major crisis on the globe and were able to react with our [sewing] machines. People are protesting the murder of George Floyd and we’re sending masks. Farm workers have to breathe in all the air from the California fires — we were able to haggle with this guy in Ktown and get them KN95 masks. We were our own shadow FEMA. That’s what felt so weird. I felt like I was running an army out of my house.

CM: Collective power can really make such a difference.

Wong: I also witnessed an unlikely army. It’s not people with guns that are going to protect, it’s people with sewing machines.

CM: COVID isn’t over. People are still getting infected every day. How is it performing a show that looks back while the issue still exists? Is that hard?

Wong: It’s very weird. [Los Angeles] is the first audience where [they’re] not required to wear masks, but most are, and some are not. And they’re within their rights.

The feedback I’m getting is the word “cathartic?” People were like, ‘We haven’t stopped to think about this.’ It feels so refreshing to describe something everybody has experienced, right? I’m not just sharing some weird thing that happened to me. We were all there, but we weren’t there together.

CM: And what came of it is you somehow made live (virtual) theater work in the pandemic. That’s an accomplishment!

Kristina Wong: I ran the “Auntie Sewing Squad” with the same mentality that I make my work. At first, it felt like we were just helping our fellow Americans, but it became clear, we have a finite amount of labor to offer. Rather than offer that labor to people who already could figure out how to get a mask, we need to figure out who [couldn’t] get one. And that becomes political because you look at who they tend to be — communities like sex workers or migrants at the border, these communities that are already on the fringe unsupported by the federal government, a lot of communities of color.

CM: I think the ‘”Auntie Sewing Squad”’ shows that when a community comes together, it has the potential to be a life-giving service.

Wong: I had many moments when people did porch drop-offs in front of my building in Ktown. I was meeting people, [and] thinking, ‘Wow, they’re so generous. And I have no idea who they are outside this context.’ I wish I always had friendships like this, just not in the context of, ‘Oh my god, are we gonna die?’ That’s incredibly powerful. Bonds were forged. We kept each other alive. We kept other people alive.

CM: What do you hope audiences who watch the show come away from it with?

Wong: When the pandemic hit, I was like, ‘ We are so connected right now, every human being, doesn’t matter who you are or what you believe in. Your health affects my health.’ That was the opportunity we missed. I got a glimpse of this community that was possible.

CM: Yeah. It’s like a microcosm. The ‘”Auntie Sewing Squad”’ is what could be—

Wong: Or could have been.