Do or Die

Grantland editor Jay Caspian Kang talks about writing, cancer and why his debut novel was inspired by the Virginia Tech massacre.

story by Y. PETER KANG

photos by INKI CHO

Jay Caspian Kang is a former disciplinary case and slacker who was jolted into success by cancer.

A quick glance at his resume would not indicate such. The bio provided by his publisher Hogarth, an imprint of publishing giant Random House, says he received an undergraduate degree from Bowdoin College, a liberal arts school in Maine, and a master’s of fine arts degree from Columbia University. His work as a journalist has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Wired and TheAtlantic.com, and he is currently an editor at ESPN spin-off Grantland, a sports and pop culture website founded by the hugely popular sports columnist Bill Simmons.

The bio does not mention, however, that Kang was kicked out of Bowdoin twice for poor behavior and even poorer grades, and had to finish his undergraduate degree at City College of New York. Or how his gambling addiction had him spending more than 40 hours a week playing poker at the Commerce Casino in Southern California while holding down a full-time gig as a schoolteacher in the Valley.

During our four-hour interview at a Koreatown watering hole, the 32-year-old tells me of his time living in San Francisco from his mid- to late-20s, waking up early to go surfing, writing in the afternoon before putting in a solid three hours or more playing first-person shooter video games. He tells me about the racism he experienced growing up in the South and how, when he begged his father to let him see a psychiatrist in high school, his father refused. Or about how his debut novel, The Dead Do Not Improve, released this month, was inspired by Korean American male anger and the Virginia Tech massacre.

If it weren’t for the cancer discovered in his thyroid, which is now gone, along with the cancer, Kang says he would probably be doing the same thing he was doing just a few years ago, which was mainly surfing, writing and wondering why nobody was interested in reading his writing.

Kang, born in Seoul, moved to the States with his family when he was a baby and lived briefly in Oregon before settling in Cambridge, Mass., near Boston. When he was 8, his parents told him they needed to legally change his name, and he was allowed to pick his own middle name. A fan of C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia series, Kang naturally opted to name himself after Prince Caspian. When Kang was 11 years old, his father’s job as a chemist—working for big corporations such as GlaxoSmithKline and DuPont—sent them to Chapel Hill, not far from the University of North Carolina.

There, Kang says he would often experience racism. Bullies would single him out during middle school just for being Asian, and he recalls a few times during high school when he and his white girlfriend would be kicked out of businesses. But he dealt with the discrimination in his own ways.

“I was such an asshole as a kid and I was so mean that it protected me from some of that stuff,” he said. “It was easy for me to figure out what people were insecure about, and when I would feel threatened, I would mercilessly point those things out.”

Kang explains that, in retrospect, it seems a harsh experience for a child growing up as one of the only Asian kids at his school, but he wouldn’t allow himself to dwell on it.

“I didn’t think about it until I got to college,” he said. “Even when me and a girl would be kicked out of an ice cream parlor or something, there would be something that would click in my brain, and I wouldn’t think about it. I’d be mad for 10 minutes, but that’s it. I wouldn’t organize candlelight vigils or anything like that.

“The way that my parents raised me and my sister was like, ‘Don’t ever think about it, just plow forward and win,’ basically. ‘If they are going to act like that, that’s their problem, you have to just be yourself. You shouldn’t apologize for who you are.’”

While Kang said he had progressive parents who encouraged him and his sister to assimilate into mainstream society, he said he was also taught from a young age to suppress his emotions.

“I remember very specifically when I was in high school and was having a lot of problems—very, very intense emotional problems and substance abuse problems. I remember going to my parents and telling them, ‘I need to go see a psychiatrist, I’m f-cking going crazy,’ and my dad’s response was like, ‘I don’t believe in any of that. I’m a pharmaceutical chemist, and I know that psychotropic medication is stupid and all they’ll do is put you on psychotropic medication.’ I still sort of reflect a lot of his opinions because of that, and I think that’s a real problem within the Korean community.”

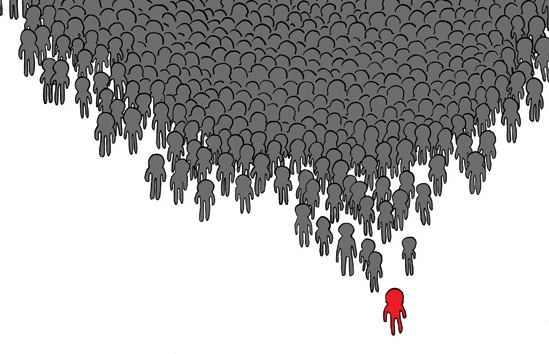

It is this understanding of how Koreans are often taught to suppress their emotions that sparked a very personal reaction from Kang when he first learned of the Virginia Tech shootings in 2007 that left 33 people dead, including the perpetrator Seung-Hui Cho, whom Kang refers to—both in his book and in our conversation—using the Korean surname first.

“You almost feel like you grew up with that violence within the culture, you almost relate to Cho Seung-Hui a little bit,” he said. “That was a profoundly f-cked up thing. This guy did one of the worst things in American history, a level of violence that was not conceivable to that point. And because you are an immigrant and part of a cultural group, you can either feel revulsion to it or identify with it. You can’t think of it in an objective way.”

Deeply troubled by the shooting, Kang says it even caused him to split from his girlfriend at the time, who was white.

“She was like, ‘I don’t understand why this is upsetting you so much.’ I said, ‘If you can’t understand, then we have no frame of reference.’ But it wasn’t her fault.”

Kang says once he heard from the TV news coverage that the shooter was Asian, he instinctively knew the suspect was Korean. “I would’ve bet all my money this guy was Korean,” he said. “That thought process is really where the book came out.”

His reaction to the Virginia Tech massacre is an experience he uses in The Dead Do Not Improve, a darkly humorous crime novel set in San Francisco’s Mission District. One of the characters, a detective named Jim Kim, tells the protagonist Philip Kim about how he simply knew the Virginia Tech shooter was Korean:

The Chinese aren’t creative enough, the Nips don’t have the balls or the specific brand of Korean crazy, which is really just the same as the Irish crazy, because both peoples come from small countries oppressed for hundreds of years by assholes across the way. Both peoples grew up under the eye of the crown or the fucking emperor and learned to suppress everything, especially anger, until they no longer could distinguish what was what, and could walk around angry without recognizing anger as anger. And the prescription for whatever else was drinking.

Kang says he wanted to write a book about Korean American male anger and the idea of growing up in violent households, while at the same time being perceived as emasculated as an Asian American outside the home, and the “weird violent mindset” that can result. “I also wanted to write about how the Virginia Tech shootings defined my generation of Korean Americans, sort of like how the [1992 Los Angeles] riots defined the older generation,” he added. “I think if I wanted to write about it, it would have to be funny, or else it would be really dark and impossible to read and come off as just ranting. That was my mission from the very beginning. I wanted to plumb the anger that is very prevalent among the males in the Korean American community.”

After finishing his novel, Kang went back to San Francisco and waited for his literary agent to begin shopping his novel around. To fill the down time, he began sending emails to sports blogs to see if they needed a writer. An underground but popular blog called Free Darko happened to be run by Kang’s high school friend, and the first thing he wrote for the blog was a piece on Jeremy Lin that appeared in January 2010. It was a well-thought-out but understandably imperfect essay comparing the then-Harvard basketball star to another American-born Chinese, rapper Jin Tha MC, both of whom were participating in fields dominated by African Americans. (He also predicted Lin had the ability to play in the NBA.)

He began writing for other sports blogs and developed a small but loyal audience on the Internet. While his love of sports had often prompted friends to encourage him to be a sportswriter, he had never envisioned himself one because of his lifelong dream of being a novelist. Still, he found pleasure in taking different approaches to writing about sports with blog posts heavily infused with seemingly random graphics and littered with YouTube clips. He had no formal training in journalism, and it showed, but his writing had razor-sharp insights, personal anecdotes people could identify with, as well as humorous hipster references, which is ultimately what set him apart from the thousands of wannabe writers floating around in the blogosphere.

Then one day, everything changed when he was diagnosed with cancer. He informs me of this fact more than halfway through our interview in a very nonchalant way. I do a double-take and ask him to repeat himself. He tells me that two years ago, his mother noticed a large swollen lump on his neck. Given that his mother’s side of the family had a history of hyperthyroidism, this is initially what she assumed he had. The endocrinologist at first thought it was a goiter, but soon figured out that it was early-stage cancer. Kang later had his thyroid removed and went through what he describes as a “relatively easy” round of chemotherapy which involved taking a radioiodine pill and a 72-hour sequestering. He now has to take a thyroid hormone pill daily.

“I have to take a pill every morning, or I’ll die,” he said, matter-of-factly.

Kang says his cancer didn’t trigger a life-affirming epiphany, like most people, but rather, an overwhelming drive to meet his career goals. “The only epiphany I had was, ‘Get yours now, do everything that you can to be as successful as possible.’ I feel like that’s a really sh-tty epiphany,” he said, laughing. “Everything happened after I got cancer. It made me into a machine-like vessel oriented only for personal success.”

Kang said over the course of the next year, he started “seeing angles” in how he could further his career and adopted a calculated, “almost Machiavellian,” way of thinking. It’s paid off, Kang admits, almost reluctantly. “If I hadn’t gotten cancer, I would be very comfortable living the life I was living.”

Kang said over the course of the next year, he started “seeing angles” in how he could further his career and adopted a calculated, “almost Machiavellian,” way of thinking. It’s paid off, Kang admits, almost reluctantly. “If I hadn’t gotten cancer, I would be very comfortable living the life I was living.”

He points out, however, that some of his best pieces—a personal essay about his gambling addiction during his early 20s that first appeared in online magazine The Morning News and an essay on then-Seattle Mariners outfielder Ichiro Suzuki—were written years before his cancer diagnosis, but simply languished due to a lack of interest.

“There was a care and earnestness I had that cancer erased,” he said.

Technically, this is not Kang’s first novel. It’s just the first book he has sold. His first novel took him five years to write and remains unpublished. The Dead Do Not Improve was written primarily in a barn on his parents’ farm outside of Seattle.

Kang, who describes himself as a “serial monogamist” and someone who has been single a grand total of three months since the age of 23, had recently broken up with another girlfriend and took refuge at his parents’ house. There, he isolated himself from the evils of the Internet and wrote the bulk of his novel, which is chock-full of insider references to Craigslist, baseball, marijuana, the Wu Tang Clan, and includes luxurious and indulgent asides similar to those utilized by The Simpsons and later beaten to death by Family Guy. When he first learned he sold his book, this serial monogamist was in Angkor Wat, Cambodia, where he had followed yet another girlfriend to Southeast Asia while she was on business.

“We were staying at a hotel there, and I woke up one morning and my agent had sold my book, and I also got an email from an editor at the New York Times Magazine [asking me to write for them] on the same day. It was a good day,” he said.

“From the time I was 15, I had always pictured the day I would sell my novel. I always pictured myself crying or calling my mom, or something like that, but none of that happened. I just moved right on to the next thing. I think I was happy for maybe like 20 minutes. I always thought it was going to be this huge weight lifted off my head and I would be able to move to Bali and surf the rest of my life, but that hasn’t been the case at all.”

After that, Kang said it was a whirlwind. Shortly after coming back to the States, Kang was at a live fantasy baseball draft with some friends when an email came in from Bill Simmons, whom the New York Times describes as “the most prominent sportswriter in America.” Simmons informed an aghast Kang that he was starting a new website called Grantland and would like him to join as a top editor. Kang says in the weeks leading up to the July 2011 launch, he often worked marathon 18-hour days at Grantland’s offices at L.A. Live in downtown Los Angeles.

With a wistful tiredness often seen in workaholics, he says his creative writing has suffered somewhat as a result of his newfound success and now-hectic lifestyle.

“I’m trying to get to when I was writing like I did when I was 23, with no concern about editors and just writing things that make me happy,” he said. “I found that the reality of being a professional writer runs counter to that.”

I ask Kang whether or not his novel’s protagonist, Philip Kim, is a thinly-veiled version of him. Both are or were creative writing grad students living in San Francisco with a passion for surfing.

“The backgrounds match up,” Kang admits with a laugh. “But it’s not me. Honestly, I think the narrator is much more earnest than I am as a person and has much more hope for himself and world than I did when I was writing this book. I think it’s a hopeful projection of myself.

“All I really hope is people who grew up with me and had the same sort of anger issues I did with the same sort of alienation will read it and feel a certain kinship to the narrator. Outside of that, who the f-ck cares?”

This article was published in the August 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the August issue, click below.