By Saturday afternoon, many of us had heard the news about football star Hines Ward getting arrested in DeKalb County, Georgia, for driving under the influence. For followers of charactermedia.com, you can see Ward, a wide receiver for the Pittsburgh Steelers, is our July cover story, and we quite unabashedly celebrate his accomplishments as a Super Bowl MVP, Dancing With the Stars champion, White House advisor and, perhaps most importantly, as an influential role model to biracial children in Korea. The July issue had come back from the printers less than 24 hours before news of the DUI allegation broke.

According to DeKalb police, Ward, who reportedly has a home in Sandy Springs, Georgia, was stopped about 2:30 a.m. Saturday on a local highway after an officer noticed his Aston Martin failing to maintain lane and hitting a curb, the Atlanta Journal Constitution reported. The newspaper said Ward failed a field sobriety test and refused to take a breathalyzer test. He told officers he had had two drinks at a downtown club, the newspaper said. Police said Ward cooperated during the traffic stop and was booked on the misdeameanor charge at 3:41 a.m. at DeKalb County jail and released on a $1,000 bond.

By Saturday afternoon, Ward’s manager, Georgia-based attorney Andrew Ree, released a statement saying, “We are currently in the process of ascertaining all the facts. From our preliminary investigation we can tell you that we are confident that the facts will show that Hines was NOT impaired by alcohol while driving. However, Hines is deeply saddened by this incident and apologizes to his fans and the Steelers organization for this distraction.”

Ree, who has known Ward and his mother Young He Ward for 20 years, told KoreAm on Monday that Ward has “always been a model citizen.

“And he is still the same man everyone knows him to be,” Ree said. “I feel confident that he will come out of this just fine.”

That said, the short-term effect is a hit to Hines Ward, the brand. The fall-from-grace angle has dominated a lot of the coverage thus far. His recent appearance on Dancing with the Stars has become more open to mockery, and his reputation as a brutal blindside blocker on the field is mentioned as if it provides a clue into his psyche.

However, in the comment sections of many Ward-related articles, it is not schadenfreude, but disappointment that reigns. People seemed to feel like they knew and trusted Ward, and they feel their trust has been betrayed. Ward has been so good at building that trust that many seem ready to forgive him. What he does with that goodwill may be his greatest public relations challenge yet.

The DUI takes nothing away from what Ward has accomplished on and off the field. The cover story focuses on his off-the-field activities, and he has had a real impact on the lives of many. This should be celebrated.

–Ed.

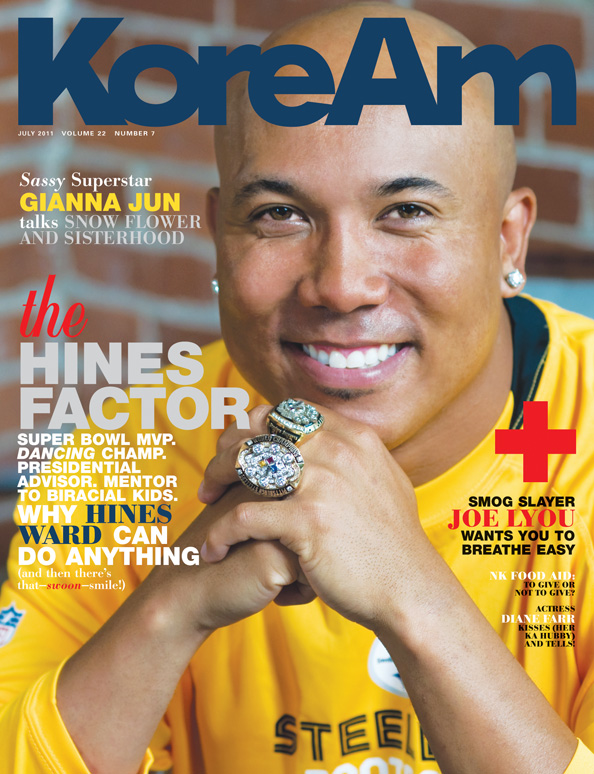

The Hines Factor

Hines Ward’s turn on Dancing With the Stars may be over, but his charm offensive on America is just beginning

by Eugene Yi

Dancing with the Stars is a staggeringly popular reality show on ABC about has-beens. The fact that it regularly pulled in 22 million viewers a week last season says less about America’s hunger for dance than our abiding fascination with the almost-famous and the recently famous and the just-were famous and the desperately-want-to-be-more famous. The best of a long-gone era of unsullied Hollywood glamor, twinkly staircase and all, is mobilized to create an institutionalized second chance. Everyone from fading reality stars to disgraced congressmen have walked those stairs.

The athletes who have appeared on the show have, interestingly, provided a touch of dignity to the proceedings. They generally appear on the show freshly retired, with the tacit acknowledgment that the Olympic medals, the Super Bowls, the stadium klieg days are done. DWTS, as it’s dubbed for short, becomes a chance to apply their immense physical gifts to one fun last hurrah. And it’s a formula that works: Athletes make up about a third of the contestants who have won or placed on the show. That is, by far, the best record of any category of contestant on the show.

So perhaps it’s not a surprise that on May 24, Pittsburgh Steelers wide receiver Hines Ward took home the top prize for the just-completed season 12 of DWTS. The Mirror Ball, as the winner’s trophy is called, now sits improbably between his two Lombardi replicas, which he got from his Super Bowl victories. But what remains a surprise is that Ward was on the show in the first place.

Ward still plays for the Steelers, of course, and is still one of the best wideouts in the game. He’s still a co-captain on the team, a vicious blocker and a spokesman known for his straight shooting on everything from concussions to his teammates’ dalliances. He’s still the franchise’s all-time leader in catches, receiving yards and receiving touchdowns. He’s still training for next season. He’s been in three of the last six Super Bowls, and it’s hard to imagine he won’t be in another. This is not a man who would seem to need DWTS.

If anything, things seem to be ramping up for Ward. His organization, Helping Hands, still works on behalf of biracial children in South Korea, a cause close to Ward, who was raised by his Korean mother after she divorced his African American father. Now, the organization is expanding its charter to help improve literacy for inner-city children. Ward also was appointed to President Obama’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders late last year. The only celebrity on the panel, he’s emerged as the public face of the group, promoting healthy habits and taking part in an anti-bullying campaign. Last month, in a ceremony in New York City, the South Korean government made Ward an honorary ambassador.

If anything, Ward seems to be the rare case where his appearance on the show has been good both for him and DWTS. This season was the most popular one to date, and the calls and emails for media appearances and endorsements have been flooding in, according to Ward’s people. Just talking about Ward’s “people” points to the curious thing about him. The scaffolding required to support 21st-century fame necessarily obscures our view of the person, and their view of us. The best we can know is what a person seems to be. Isn’t that how we usually talk about celebrities? So-and-so seems like this or that. Once this seeming quality turns unstable, we start to question not ourselves, but the celebrity.

But there seems to be a stable quantity at the core of the Celebrity Known as Hines Ward, from his days growing up as a bullied biracial kid in Atlanta, to being nearly overlooked as a third-round draft pick, to the Super Bowl XL MVP trophy and the whirlwind tour of South Korea in 2006 with his mother that first made him a celebrity there, and now, with his win on one of America’s most popular shows.

Everything spins faster and faster, but there’s Hines Ward, still flashing that million-dollar smile, still talking up his immigrant mom as his mentor and his inspiration, still doing and saying the right things with an effortlessness that reads as authenticity. Humility. Integrity. All traits that those close to him bring up again and again. This is a man who can get mistakenly handcuffed by the Los Angeles Police Department, as he was in May, and still seem like a winner (From his Facebook page: “The police were just doing their job. Apologies were made and it’s now in the past. Moving forward … Hines”). This is a man who can be on a show like DWTS and somehow avoid seeming like just another celebrity, desperate for attention. This is a man whom, as one high-level White House staffer put it, Korean American moms love. And if Korean American moms love him, he must be doing something right. He just might be the most famous Korean American in the world right now, and for once, it seems like it’s for the right reasons.

***

Pittsburgh 25, Green Bay 31. Super Bowl XLV ended in defeat for Ward’s Steelers. He finished with seven receptions for 78 yards and one touchdown, but it wasn’t enough.

“I was depressed after losing the Super Bowl,” Ward said. It looked like it’d be a quiet offseason for Ward. But with next season in limbo due to labor negotiations and an owners’ lockout, Andrew Ree, Ward’s manager, saw an opportunity.

“I told Hines that DWTS would be a great way to not think about the lockout and to stay in great physical shape in the offseason,” Ree said. “I wanted him to be the first active player to ever win the Mirror Ball.”

Ward was initially resistant.

“This is my off-season. This is my time to go home, be a father, take my son to school,” he said. If Ward made it deep into the show, his son Jaden’s school year would be over, taking away the chance to do even that. The time with his son, who is 8, is probably even more important for the recently divorced Ward. But he said Jerome Bettis, the garrulous retired halfback for the Steelers, once gave Ward some advice: Do everything. You may not want to. You may be tired. You may want your offseason. But do everything. Because once the football career ends, it will matter.

So, a few short weeks after the Super Bowl, Ward was learning his first dance steps in Los Angeles.

Ward smiles on the sideline at the preseason Carolina Panthers game at Heinz Field on Sept. 9, 2010.

Ward smiles on the sideline at the preseason Carolina Panthers game at Heinz Field on Sept. 9, 2010.

The reactions from Ward’s circle were predictable.

Corey Allen, friend: “I laughed long, and I laughed hard.”

Young He Ward, his mother: “I’m shocked, really. I tell him, ‘You don’t know nothing about the dancing.’”

James Farrior, Pittsburgh Steelers inside linebacker: “Me and all my teammates thought the same thing: He’ll last maybe like a week or two, and then he’ll be gone.”

Farrior got an early peek at Ward’s ballroom efforts, though, and he quickly came around. “[Ward] showed me a video of one of his practice tapes, and I was like, ‘Wow.’ I told him right then, you can win,” he said. The rest of his teammates quickly followed suit.

“Every Monday, guys were planning around seeing me dance,” Ward said.

The teammates’ enthusiasm must have been gratifying, but for Ree, who speaks at the breathless clip of someone who’s already five minutes late for his next meeting, the goal of Ward’s participation was to reach a different audience. “With him playing only a few more years, I felt that now was the time to begin that transition from football to life after football,” Ree said. “I wanted him to gain a broader fan base and connect with that part of the population who knew next to nothing about football.”

Ree said he studied the reality show market and considered other contests as well: Celebrity Apprentice, Survivor and Big Brother. But DWTS won out. It’s a much more popular show, for starters. But it also was the only one where Ward would really be in control of his own fate. No alliances, no teammates. Just good old-fashioned hard work. Ree, who has known Ward for about 20 years, felt good about his chances.

“He was made for the show,” Ree said.

***

Attendees for a taping of DWTS are given the following advice regarding dress code:

“This is a glamorous show, and a beautiful looking audience is a crucial part of the overall atmosphere, with that being said we ask the ladies come dressed in fancy cocktail attire, or a nice pants suit and gentlemen wear a jacket and tie or if you can’t bear the thought of both please wear one or the other.”

[ad#bottomad]

For the May 16 semifinal taping that I attended, most attendees heeded the advice. The glamorous apparel contrasted sharply with the Terrible Towels, the black-and-yellow identifying mark of any Pittsburgh Steelers fan. Indeed, fans of Ward outnumbered those for all other contestants combined. Or, at least, outshouted them.

Ree sat in Ward’s friends-and-family cheering section, right by the orchestra, as did two young women who had come from South Korea via Spokane, Washington. Earlier in the day, when I met Jamie Boyd and Suan Yoo, both 20 years old, both biracial Korean and African American, they spoke English perfectly. Or, at least I thought they did, until I noted the shortening of vowel phonemes and the occasional emphasis on the wrong syllable—the host of telltale indications that Korean was their first language. I asked if they’d be more comfortable conducting the interview in Korean or in English, and they said, nearly in unison, “Korean!” When they switched, it took me aback. The sight and sound of biracial faces conversing masterfully in Korean felt incongruous, like one of those shows where they invite non-Koreans to speak Korean. And if I, as a born-and-raised American accustomed to ethnic diversity, had this reaction, I couldn’t help but think how much more extreme the reaction could be in South Korea. It’s always discomfiting to find the seeds of discrimination in oneself.

All of this, of course, quickly left my mind as I was repeatedly shamed by their helpless giggling at my vain attempts to speak Korean. But more to the point, they are exactly the people whom Ward’s foundation was meant to help.

The two grew up fatherless in Dongdu-cheon, near the Camp Casey U.S. army base, about two hours north of Seoul. Their fathers were African American military men, both of whom left before Boyd and Yoo were born. Both attended schools near the base, and so were surrounded by other biracial children, or Amerasians, as they are referred to there.

“I always went to international school, so I grew up around Amerasians,” said Boyd. “Outside of school, everybody would look at me weird and stuff.”

The toxic quality of the looks was apparent to Father Alfred Carroll, who has been mentoring biracial Korean children for decades. Carroll, a Jesuit priest at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, first visited South Korea in 1980, and said it was impossible to escape the xenophobia.

“One of the things that amazed me was I was stared at all the time there,” he said.

“Meeting the Amerasians, these kids get stared at all the time. I’m an adult and I can handle it, but as a kid, it’s terrible.” The hallowing of the homogeneity of the Korean race has become a central part of the more rigid outlook on Korean identity, something Carroll attributes to the nation’s history of being invaded. It’s even been codified into the pure blood theory, a notion so ingrained in Koreans it has its own Wikipedia page.

Yet, in 2006, South Korea embraced Ward, who was crowned the Super Bowl MVP that year, with the fervor of a long-suffering small market city celebrating its suddenly victorious home team. Presidential trips, daily television appearances, a phalanx of reporters wielding boom mics and cameras following his every move. South Korea had, impossibly, lionized a biracial Korean.

“Everybody was like, ‘Oh, Hines Ward is Korean,’” said Boyd. “But we are, too,” she recalled thinking.

The disconnect was apparent to Ward as well, which is what led him to start his foundation.

“For Korea to sit there and jump on the bandwagon of my celebrity status, and turn around and tease these kids, it just didn’t seem right to me,” said Ward. “So I just wanted to let those biracial kids know that you can do big things. You can’t change the world overnight. But the more I can show the positive light of being biracial, and showing everyone in the world biracial kids can do anything, the better.”

Some things have changed, thanks in part to Ward’s efforts. In 2006, biracial Koreans could not serve in the military; now, they can. Boyd and Yoo now study at Spokane Community College in Washington, something that they say would’ve been impossible without Helping Hands and the nonprofit Pearl S. Buck International, which works to foster the acceptance of biracial children in South Korea.

Every year the two organizations sponsor a group of children to come to the U.S., take in a Steelers game and spend a week living in America. Boyd and Yoo took part in two of these trips. They speak fondly of their time in the States, and of the influence that only a celebrity of Ward’s stature can yield.

Whenever people ask me, I just say, ‘I’m Korean.’ Now, it’s so natural for me,” said Boyd, who is studying cosmetology. “But before, I didn’t really want to talk about it. It kind of made me grow, seeing how [Hines] handles stuff, and just seeing him, it just changed everything.” She hopes to return to South Korea and find work doing hair and make-up for television.

Yoo, who wants to transfer to a four-year university and pursue a career in hotel management in the U.S, said she still gets looks when she’s in South Korea, and she hates that. And even in the U.S., she’s never felt comfortable with either the Korean American community or the African American community. Still, Yoo, who often hides behind her bangs, credits Ward with helping her accomplish more than she ever thought possible.

“Before I met Hines, I couldn’t have imagined studying in America. He made a big difference,” Yoo said.

“Hines Ward is such a hero in my eyes,” said Janet Mintzer, the president and CEO of Pearl S. Buck International. She has known Ward since her organization started working with Helping Hands in 2006. “I see his heart,” she said. “He’s really genuinely caring and nice.”

She laughed ruefully at one moment that, despite extensive media coverage of the trips to Pittsburgh the Amerasian kids make, had been missed by the cameras.

The end of the trip is celebrated with a big dinner where the kids each read a speech for Ward. A young man named Michael talked about how, after watching how Ward treated his mother, vowed to treat his own mother better. Mintzer said Ward started tearing up during the speech, to the point that his son ran to his father and asked what was wrong.

Mintzer recalled approaching Ward’s mother and telling her how impressed she was by his sensitivity.

“Oh, he cry all the time. He big baby,” Ward’s mother said.

***

Before the taping for the semifinal show of DWTS, Ree had a warning for Ward.

“I told him: Don’t look at the monitors,” Ree recalled. While rehearsing a difficult lift, Ward had fallen on top of his partner Kym Johnson, and she’d landed awkwardly on her neck. Johnson was placed on a gurney and taken to the emergency room. Fortunately, Johnson had managed to avoid serious injury, but Ward had been quite shaken by the incident, which occurred the Friday before the Monday semifinals. Ree knew that footage of the accident would be replayed on the monitors during the training montages that precede every dance, and the effect it would have on Ward.

“So [Ward] put his head down. But he didn’t realize they were going to show it again in slow motion,” Ree said. “He started to cry before he even started performing.”

Yet, once the orchestra started playing the peppy “Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps,” Ward kept his face in a rigid display of pre-tryst breathlessness, all parted lips and aggression, boldly leading his leggy partner through the sultry Argentine tango. Then, once the music stopped and the cheers erupted, the tears flowed.

And not just Ward’s. A choked-up judge Carrie Ann Inaba told the wideout-turned-dancer: “I’m so impressed with you and how you partnered her through that routine. That routine would’ve been very dangerous for her, and I saw the way you supported her. The connection was beyond what we ask for in a dance routine.” The couple went on to receive perfect scores.

After the show, according to Ree, Inaba told him, “Out of all these years on the show, that’s probably the most compassionate moment we’ve had.”

“People are there crying at home,” Ree added. “It was a defining moment.”

And to think, Ward could’ve instead been on Celebrity Apprentice, getting fired by the Donald.

Moments like that affirm Ree’s hunch that Ward was indeed made for the show.

“I’m walking in the mall here in L.A., and people know me from my dancing,” Ward said, laughing. “They don’t even know nothing about football.”

“You’re going to see his face on a few more things on television as a direct result of this,” Ree said. He declined to go into specifics, but said he had received interest from everyone from Kia to the major American television networks. It all hews nicely to Ward’s post-career plan to work his way into the broadcast booth.

Listening to Ree talk, it’s difficult not to get excited about the intellectual challenge of promulgating a celebrity. Ree’s right; Ward, 35, has only got a few years of football left in him. And athletes have a different relationship with fame than actors or musicians. For other celebrities, fame is cultivated; it is the sine qua non of success. But for athletes, the fame is incidental. It happens as a direct result of what happens on the field. And so, for many athletes, once the field performance is gone, so is the fame, so is the money.

“I think the problem with a lot of guys in the NFL is that we think we’re going to play forever,” said Farrior, the Steelers’ linebacker. “It’s something we’ve been doing since we were little kids,” he added, and it’s hard to imagine doing anything else.

It goes back to Jerome Bettis’ advice: Do everything. So Ward cheerfully agrees to interview after appearance after photo op, grinning and saying the right things. He agrees to be on DWTS, comes out looking like a winner and actually wins the whole thing to boot.

“I’m preparing for it. I want to make that smooth transition. So I’m not just sitting out and wondering,” Ward said.

“I’m just having fun. I just try to take it one thing at a time,” he added. Clichés, to be sure, but such earnestness seems like a natural extension of Ward that it’s hard to be cynical.

***

Everyone interviewed for this article has a pretty good Hines story. Ree is no exception.

The Atlanta-based attorney first read about Hines Ward in the sports section of the local newspaper. Ward was in high school at the time, and the article focused on the youth’s pride in his Korean heritage and his relationship with his mother. Ree grew up in Florida without the benefit of a Korean American community, and Ward’s ethnic pride struck a chord. Ree called him up and asked to take him and his mother to dinner. Ward, thinking Ree was a recruiter from the University of Georgia, accepted the offer. Ree dispelled the notion, and they had a nice dinner. It ended with Ree offering his services as an attorney, if Ward ever ended up needing anything. A week later, Ward called and asked if Ree could help him and his mom understand the recruiting process, since Ward was already getting calls from college scouts.

“We have been together ever since,” said Ree, 50. “He is like a brother to me, and his mom is like an aunt. I love them both like family.”

This sort of thing seems to happen for Ward. It reinforces the central assumption we have about him: that he’s a good guy. Even as his fame has grown, there has been little to sully the impression. He seems to be stronger than the modern American celebrity machine. And for a man who has been the defender of biracial children in South Korea, a four-time Pro Bowl selection, a two-time Super Bowl champion, the Super Bowl XL MVP, a likely Hall of Fame inductee, a presidential advisor, an honorary ambassador, and a Dancing With the Stars champion, Hines Ward’s greatest accomplishment may be that, somehow, he seems to still just be Hines Ward.

This story was published in the July 2011 issue of KoreAm.

[ad#bottomad]