Confession: when I first moved back to L.A. from the Bay Area in 2006, an early food revelation was realizing that there was more to Korean cuisine than just barbecue. When I lived up north, the Korean food I encountered came either in the form of charred galbi (short rib) strips meant to feed broke college students—shout out to Steve’s Korean BBQ in Berkeley—or more expensive but middling barbecue spots where I wondered, “For these prices, why do I have to grill this myself?”

My youth and ignorance were mostly to blame, and luckily, the sheer size and influence of Korean food in L.A. meant that returning here gave me a second chance at forming a first opinion. Thanks to the late food writer Jonathan Gold, a consummate cheerleader for Korean cuisine in the Southland, I had a guide of where to begin devouring swaths of new dishes.

I distinctly remember the first time friends and I went to Ondal 2, which specializes in kkotgetang (spicy crab stew). Once we had plucked out all the crab parts, a server brought over a kettle of gochugaru-laced broth. As the pot returned to a murmuring boil, she hand-pulled noodles into it as a second course. And then, when we had finished that, she came back with a heaping bowl of rice and a squeeze bottle of slick, crimson gochujang and made us fried rice in the same pot. I was awestruck at how one dish turned into three and wondered, “Whoa, how come my [Chinese] people don’t do this?!”

These days, I probably eat at least three Korean meals a month, often gravitating towards soups and stews. On cold days, there’s the bubbling warmth of soontofu, and during heat waves one can slurp down a sweet, icy serving of naengmyeon noodles. I love various beef tangs (soups), whether it’s a milky bowl of long-simmered seollongtang (the broth extracted from beef or ox bones) or a crock of galbitang, rich with droplets of rendered beef fat. However, there’s nothing I like better than gamjatang (pork neck stew), especially when it arrives to the table on a low boil, with heaps of pork bones dotted by tiny perilla seeds.

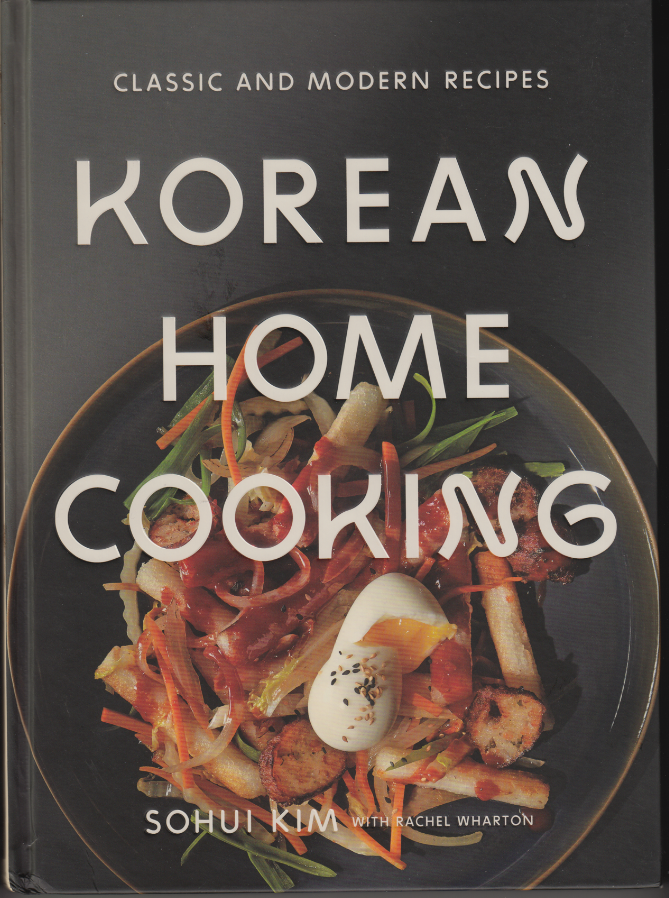

For all my Korean dining out though, until recently, I had rarely tried making similar dishes at home. I went looking for a copy of “Korean Home Cooking,” the latest cookbook from New York chef Sohui Kim (“The Good Fork Cookbook”) and co-writer Rachel Wharton. It’s been an in-house favorite of Michelle Mungcal and Ken Concepcion, the Filipino American couple who run Now Serving, the cookbook store in L.A.’s Chinatown that’s been my essential resource in writing this column. However, every time I stopped by, they were out of stock. “I think Angelenos really love the flavor profiles in Korean food and have always been very interested in learning their favorite dishes at home,” Concepcion told me. But finally, on my most recent trip, he found one last copy of “Korean Home Cooking” in the back and thus launched several weeks of my, uh, Korean home cooking.

Like other Asian American chef-slash-authors, Kim was first trained in classic European culinary techniques. Her first restaurant, The Good Fork, includes a few Asian touches such as salt cod taiyaki on the menu, but the cuisine is mostly New American. In contrast, “her second eatery, Insa, is what she describes as “100 percent Korean—dedicated to traditional flavors, recreated and reinvented in small, subtle ways.” “Korean Home Cooking” clearly draws from Insa; many of the same dishes appear in both the cookbook and the restaurant.

One thing I learned immediately: buy you some gochugaru. Initially, I was surprised this ground red pepper didn’t seem to come in anything smaller than a one- or two-pound bag, but I soon realized why: It’s essential in Korean cooking and the primary reason why everything from kimchi to yukgaejang (spicy beef soup) to tteokbokki (stir-fried rice cakes) comes streaked in vermillion shades of red, with a mild, piquant spiciness.

You’ll also want to stock up on the sweeter gochujang sauce, and as with other East Asian cuisines, you can never have enough garlic or ginger on hand. One of the first dishes I tested, Kim’s dakdoritang (spicy chicken stew) uses copious amounts of all the above, plus soy sauce and scallions to produce a remarkably easy but satisfying one-pot dish of tender, savory chicken and potatoes that’s enough to feed a small dinner party.

Another night I used those same base ingredients for a baby back rib recipe that looked incredible and tasted nearly as good. By adding rice wine vinegar, black pepper and a touch of honey, the barbecue sauce that basted these ribs shares much in common with the sweet, spicy and acidic profile of Memphis-style sauce but tastes completely different.

Speaking of barbecue: while “Korean Home Cooking” isn’t meant to be a history book, I did learn through it that the Korean galbi that I grew up eating—flat and thin—originated in Los Angeles because Korean immigrants in the 1970s could only find short rib cut in this “flanken” style, rather than the thick and squat “English cut” used in traditional South Korean preparations. The “L.A.-style” galbi is easy to find and quick to cook, but once you’ve made galbi with the meatier English-cut, you may find yourself a convert to the old school prep.

Astute readers will notice I haven’t written anything yet about banchan, those ubiquitous small dishes that typically accompany Korean restaurant meals. Much as I appreciate banchan when I eat out, small or not, they often require as much effort to make as an entree, and I have yet to develop a routine to apportion the time to prep a half-dozen side dishes. I did make an exception for Kim’s scallion salad recipe, even if it took me at least five minutes per stalk to slice nice, thin slivers. It’s time-consuming but the scallions, curled from a lengthy soak in ice water and tossed with vinegar, gochugaru and sesame oil, paired well with practically every other dish I made thanks to its bright acidity and the unique flavor of toasted sesame.

“Korean Home Cooking” offers up 125 recipes, which meant that after two weeks I had made only a tiny dent into its full array. I was a little disappointed that despite that bounty Kim didn’t include a recipe for my beloved gamjatang (even though she serves it at Insa), but I found other porcine dishes to soothe my pain, including a simple cured pork jowl dish that went beautifully when brushed with a little sesame oil and salt, then topped with a few slivers of that scallion salad. Moreover, for a chef-authored cookbook, the recipes were generally easy to follow, though anyone attempting one of her many kimchi preparations needs to remember that fermentation takes time—you’re not going to have classic baechu (napa cabbage) kimchi on the table if you haven’t started it days in advance.

The diversity within Kim’s cookbook was a wry reminder of all the years I squandered on a hilariously narrow conception of Korean cuisine. But between access to America’s most robust Koreatown and books like Kim’s and others, at least I have the opportunity to make up for all that wasted time.

Oliver Wang is a professor of sociology at CSU-Long Beach and writes on music, food and culture.

This article appeared in Character Media’s April 2019 issue. Subscribe here.