SEOUL — Moon Jae-in declared victory in South Korea’s presidential election Tuesday after his two main rivals conceded, capping one of the most turbulent political stretches in the nation’s recent history and setting up its first liberal rule in a decade.

Moon, a liberal former human rights lawyer who was jailed as a student by a previous dictatorship, favors closer ties with North Korea, saying hard-line conservative governments did nothing to prevent the North’s development of nuclear-armed missiles and only reduced South Korea’s voice in international efforts to counter North Korea.

This softer approach might put him at odds with South Korea’s biggest ally, the United States. The Trump administration has swung between threats and praise for North Korea’s leader.

Moon, the child of refugees who fled North Korea during the Korean War, will lead a nation shaken by a scandal that felled his conservative predecessor, Park Geun-hye, who sits in a jail cell awaiting a corruption trial later this month.

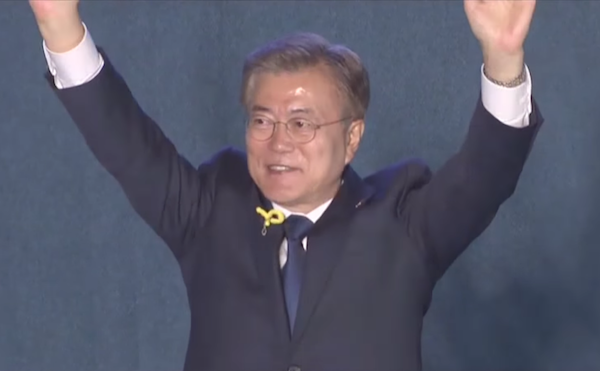

Moon smiled and waved his hands above his head as supporters chanted his name at Gwanghwamun square in central Seoul, where millions of Koreans had gathered for months starting late last year in peaceful protests that eventually toppled Park.

“It’s a great victory by a great people,” Moon told the crowd. “I’ll gather all of my energy to build a new nation.”

Tuesday’s election saw strong turnout — about 77 percent of 42.5 million eligible voters. Moon had a relatively low share of the total vote — 41.4 percent according to an exit poll — but there were many more major candidates than in 2012, when Park won 51.5 percent, beating Moon by about a million votes.

Over the last six months, millions gathered in protest after corruption allegations surfaced against Park, who was then impeached by parliament, formally removed from office by a court and arrested and indicted by prosecutors.

Moon’s two biggest rivals, conservative Hong Joon-pyo and centrist Ahn Cheol-soo, were expected to garner 23.3 percent and 21.8 percent, respectively, according to the exit poll, which had a margin of error of 0.8 percentage points.

Moon will be officially sworn in as South Korea’s new president after the election commission finishes the vote count and declares the winner Wednesday morning. This forgoes the usual two-month transition because Tuesday’s vote was a by-election to choose a successor to Park, whose term was to end in February 2018.

Moon will still serve out the typical single five-year term.

Moon was chief of staff for the last liberal president, the late Roh Moo-hyun, who sought closer ties with North Korea by setting up large-scale aid shipments to the North and by working on now-stalled joint economic projects.

Hong, the conservative, is an outspoken former provincial governor who pitched himself as a “strongman,” described the election as a war between ideologies and questioned Moon’s patriotism.

Park’s trial later this month on bribery, extortion and other corruption charges could send her to jail for life if she is convicted. Dozens of high-profile figures, including Park’s longtime confidante, Choi Soon-sil, and Samsung’s de facto leader, Lee Jae-yong, have been indicted along with Park.

Moon frequently appeared at anti-Park rallies and the corruption scandal boosted his push to re-establish liberal rule. He called for reforms to reduce social inequalities, excessive presidential power and corrupt ties between politicians and business leaders. Many of those legacies dated to the dictatorship of Park’s father, Park Chung-hee, whose 18-year rule was marked by both rapid economic rise and severe civil rights abuse.

As a former pro-democracy student activist, Moon was jailed for months in the 1970s while protesting against the senior Park.

Many analysts say Moon likely won’t pursue drastic rapprochement policies because North Korea’s nuclear program has progressed significantly since he was in the Roh government a decade ago.

A big challenge will be U.S. President Donald Trump, who has proven himself unconventional in his approach to North Korea, swinging between intense pressure and threats and offers to talk.

“South Koreans are more concerned that Trump, rather than North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, will make a rash military move, because of his outrageous tweets, threats of force and unpredictability,” Duyeon Kim, a visiting fellow at the Korean Peninsula Future Forum in Seoul, wrote recently in Foreign Affairs magazine.

“It is crucial that Trump and the next South Korean president strike up instant, positive chemistry in their first meeting to help work through any bilateral differences and together deal with the North Korean challenge,” she said.

By Hyung-jin Kim, Foster Klug