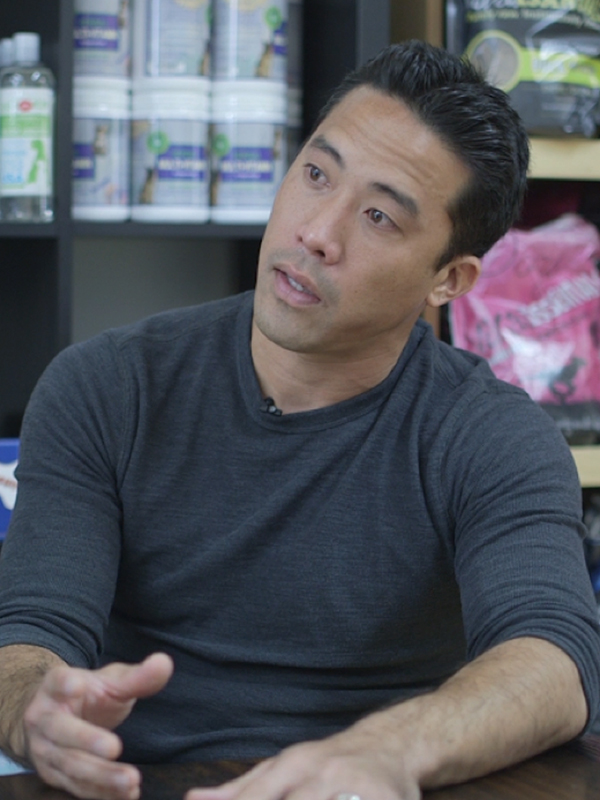

It’s a sunny May day in Sherman Oaks, California. Inside the Petstaurant, an organic pet food store, owner Marc Ching sits, red-eyed and repeatedly apologetic for his tears, as he swipes through a gallery of videos from an iPhone nestled in his palm.

“This one’s maybe a two or three,” he says, and stops at a still shot of a dog being dragged into the back of a Thai slaughterhouse. Ching is as numb as can be. He’s assigned levels, from one to 10, to the graphic scenes of torture he’s documented, mostly captured on this very same smartphone, through six trips to Asia. Ching’s shoulders tense as his index finger finds the play button. “I’ve got videos that are nines and tens. This one here, you don’t actually see the torture. He’s dragging the dog to the back — there, you can see he’s got a sledgehammer.”

When the video begins, the blunt instrument swings into view, through a small window to a back room. It strikes down. True to his word, there’s no dog in sight. But the yelps and howls and wails are there, one after the other, and they’re loud.

“It’s torture,” Ching says, pausing the video. His voice hasn’t lost its shakiness in the minutes following a question about what he’s witnessed in Asia. “He could kill it in one strike, but he’s torturing that dog.”

There’s more videos, a lot more. In one, a restrained golden retriever is beaten on the head by a hammer. In another, children strike a hanging pup with what looks like a pipe. There’s one in which a dog is roasted alive with a blow torch.

Ching, who heads both the store and the Animal Hope and Wellness Foundation, has run a largely one-man operation, making trips to Asian countries like China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand and South Korea since September to rescue tortured and abused dogs in the dog meat trade, usually by posing as a buyer. Of those he pulls to safety, some don’t make it. Some remain in their home countries, unable to pass inspection. And some come home to Ching’s foundation, which also takes in dogs from local abuse cases, and finds them permanent homes.

According to the Humane Society International (HSI), 30 million dogs a year are killed in the dog meat trade; last year, some 2,000 to 3,000 dogs were killed for the dog meat festival in Yulin, China, alone. Ching documents his trips real-time via Facebook, where he uploads videos, urges action and updates his followers on the conditions of the dogs whose lives he saves.

“Change is so close,” Ching says. “Once you show the world what [slaughterhouses] are doing, I think one out of 100 people won’t care, and the rest will.” Ching’s goal is to see reform in government laws through his documentation and through the voices of those he can affect with his stories.

***

Ching is not alone in attempting to bring about an end to this business. In Thailand, an organization called Soi Dog Foundation was instrumental in making dog meat illegal by showing a link between the meat and rabies. HSI is making a similar effort in Vietnam, citing research by the World Health Organization that found that the dog meat trade spreads rabies and increases cholera risk twenty-fold. In China, HSI has also worked with local groups like the Chinese Animal Protection Network to organize protests and to gain legal custody of a handful of animals.

Adam Parascandola, HSI’s director of animal protection and crisis response, said the organization is also working toward appealing to local lawmakers. “It’s about showing governments that these farmers do want to get out of the [dog meat] business,” Parascandola said. Since January, HSI has rescued 485 animals from dog farms in South Korea and helped five dog farms transition into other businesses. “Changing the laws has to be the goal.”

News of the Yulin festival spurred Ching to action for the first time last year. Dog meat consumption and abuse is largely cultural — locals believe the meat possesses added health benefits and tastes better if the animal is tortured first.

Ching’s first trip to Asia involved no pre-planning. He simply rescued dogs and came back feeling like a hero, he said. But when his undercover visits to the slaughterhouse began, a world of trouble followed, including being beat up, assaulted and hospitalized. By the fourth trip, Ching had had a breakdown. And after the sixth, he nearly lost himself.

“The torture I saw was extreme,” said Ching. It broke him apart. “I’m always writing that, even in the ugliest and darkest person, there’s still one piece inside that’s good. But in that moment, you lose hope for humanity. If there’s no hope, anything I do is worthless. If I can’t change the mindset of a human being and I can’t instill compassion, then what am I doing out there? I lost the faith I’d always had. When I came back home, my mind couldn’t process everything and I shut down. I think people were scared for me.”

Every time he goes undercover he is putting himself through a kind of mental and physical distress from which he may never recover. The seventh trip — on which he embarked mid-June — was his last. “I wonder if people are going to look at my decision and think of me as a coward, but I just can’t [do this anymore],” he said. “I feel like I’m going to die so much internally that I just don’t know how to live. I have to make a choice for my family. To die out there, that would be terrible. But to die emotionally, that’s so much worse.”

***

The rescued dogs that have made it back to California with Ching are undergoing different transformations. Zoe, a dog from Thailand, is missing both legs and still adjusting. Faith, a dog from a torture chamber, was so scared at first that she would not let anyone touch her. It was with the help of a loving foster family that she found a new life. Now, Ching said, “You wouldn’t even know that [Faith] was ever tortured. It’s why I do what I do, because in the end it’s beautiful.”

Betty, another dog from Thailand, is missing one of her back legs. Kezia Jauron, a foundation volunteer, and her husband Gary have taken Betty in as a foster. “I think [fostering] makes us better activists, makes us better advocates, and we just do a better job speaking up for the cause when we have opportunities to have a relationship with these animals,” said Jauron, who has experience in providing temporary homes for animals with a traumatic history.

Before setting off on his final 16-day trip, which he calls the Compassion Project, Ching said he hoped to save hundreds of dogs, continue documenting slaughterhouses, help shut down dog meat restaurants in the Yulin area to discourage the festival and participate in anti-festival activist efforts.

On June 14, Ching posted to Facebook that the foundation had reached an agreement to transform a Cambodian slaughterhouse that kills 20 to 60 dogs a day into a vegetarian noodle house. The operation was ripped down with the same hammers and machetes used to torture the dogs. “I thought it was a fitting end,” he wrote. “We ripped the walls off. Pulled the floorboards up. And got the villagers to help us crumble death into the ground.”

Seven days after that, Ching was back on Facebook with news that he and his team, with the help of a local organization and HSI, had shut down six slaughterhouses and rescued more than 1,000 dogs from being killed and eaten at the festival.

Ching found help this time around from people who have heard his story — volunteers, including five former special forces members from the United Kingdom, have flown in to lend their hands. Matt Damon, Joaquin Phoenix, Kate Mara, Maggie Q and Kristin Bell, among others, joined a PSA campaign by the foundation to urge others to oppose the dog meat festival.

“Change, it is possible,” Ching wrote on Facebook this month. “It is real. And it is right here, on the edge of that horizon. I believe — because hope is something worth believing in.”