A Family Affair

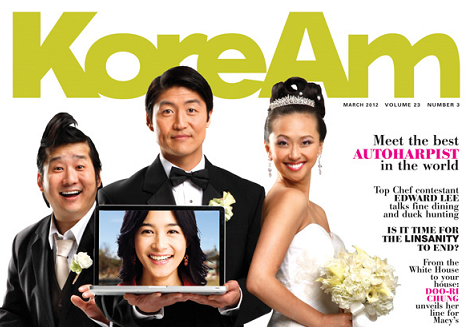

Wedding Palace is a romantic comedy about a quirky Korean American family that will be hitting theaters nationwide later this year. KoreAm spoke with writer/director Christine Yoo and leading man Brian Tee for a behind-the-scenes look at how the movie— filmed with two separate crews in the U.S. and Korea—got made, how Yoo wouldn’t take “no” for an answer and how a community said “yes” to a dream.

by Oliver Saria

They say to make it in Hollywood, it takes moxie, grit and a bit of good luck. You might want to add a PowerPoint presentation to the list.

“I had a PowerPoint presentation, and I literally walked in off the street and would talk to anybody that would talk to me,” Christine Yoo, director of the romantic comedy Wedding Palace, tells me as we sit in a coffee shop in Los Angeles’ Koreatown, where much of the film was shot. “If I wanted to shoot here in this location. I would just come in, I would introduce myself, and I would ask who do I need to talk to.”

Her ambitious indie film certainly needed all the production help it could muster.

With a sizable cast, a flashback sequence set during the Joseon Dynasty, and the film touted as the first U.S.– Korea independent co-production, Yoo had no choice but to go big.

Wedding Palace tells the tale of Korean American Jason Kim (played by Brian Tee of The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift) doomed by an ancient family curse to die if he does not wed by his fast-approaching 30th birthday. Left at the altar by his fiancée (played by Joy Osmanski), Jason must contend with a family frantically scrambling to find him a new wife, and thus save his life. But Jason chooses to tempt fate by holding out for true love, which he finds during a business trip to Korea, embarking on a long-distance, online relationship with the enchanting Na Young Song (played by Korean starlet, Kang Hye-Jung, the ingénue in the critically acclaimed classic, Oldboy, in her first English-speaking role). But when the family finally meets Na Young, some aren’t convinced she’s the right one to break the curse.

The film also costars familiar Korean American actors of film and TV: Stephen Park (Fargo, In Living Color) plays Jason’s father; Bobby Lee (MadTV, Pineapple Express) steals scenes as Jason’s best friend; and Margaret Cho hilariously chews the scenery as a shaman.

Yoo began writing the script back in 1999 with the aim of developing a multigenerational Korean comedy with crossover appeal. She eventually sought help from her former professor (and the film’ s eventual co-writer), Robert Gardner, at the University of Southern California, where she studied film. The script made the rounds of production companies around Hollywood, attracting some interest. “In 2000, a producer I had been working with submitted it to a finance company who was deciding between two wedding related films: one Korean and one Greek,” recalls Yoo. “At the time, I was like, Greek? That is so obscure.” Of course, that obscure script went on to become My Big Fat Greek Wedding, which tops “The List of 15 Most Profitable Movies of All Time,” according to CNBC.

Yoo shopped the project to studios in Korea, China and Japan, but after everyone passed on the film, she decided to turn to her own backyard, Los Angeles’ Koreatown, to make the film on her own, nearly eight years after its inception.

“I felt like it was a do or die moment for me,” she proclaims. After working for nearly a decade as a professional film and television writer whose credits include co-writing the animation series Afro Samurai, Yoo says, “I had just gotten to the point where I couldn’t take it anymore. I came out here to Hollywood to become a director.”

But while Yoo, who used to work as an editor at KoreAm Journal in the early 2000s, felt very connected to Koreatown as a Korean American, she couldn’t quite claim it as her own, having been born in Buffalo, N.Y., and raised in Iowa City and later Memphis, Tenn., where her father was a physician and university professor.

For an entree into the Los Angeles K-town community, she could not have chosen a better leading man than Brian Tee, who also served as one of the film’s producers. To say that his roots run deep in K-town would be like saying Kobe has a decent jump shot. When I interviewed him at yet another coffee shop in K-town, we were interrupted twice: once by his aunt who owns the jewelry store on the third floor of the galleria where we met and again by his mother, now retired from the same said jewelry store and who also happens to have a small role in the film.

One of the things that initially attracted Tee to Wedding Palace was its multigenerational appeal and its loving portrayal of a tight-knit Korean family, which mirrored his own in many ways. “It was one of the first scripts that I laughed out loud [while reading], literally,” he recounts. “At the time I was taking care of my grandmother and I was upstairs, and I can remember her from downstairs asking if I was OK because she could hear me laugh so hard.”

Upon graduating from the University of California, Berkeley, with a degree in dramatic arts, Tee, who grew up in Hacienda Heights, Calif., moved to the edge of K-town with his ailing grandmother, a spiritual advisor to many in the community. “What I thought would be one or two years ended up being a solid 11 until the end of her beautiful life,” says Tee, born in Okinawa to a Korean mother and Japanese father.

Before his grandmother’s passing, she conducted the traditional Korean gosa ritual for the film, where celebrants stuff money into the head of a pig to bless the start of business ventures. “That was the last time she stepped out of the house prior to taking her to the hospital. She did way more for me than I could ever do for her. This movie means so many things on so many levels, you don’t even know,” he attests.

Emboldened by Tee’s close ties to K-town, he and Yoo approached Johng Ho Song, executive director of the Koreatown Youth and Community Center. Song appreciated the fact that the film aimed to celebrate Korean culture and was not of the horror or gangster genres. “It was their passion, their dedication and their commitment to the project that convinced me,” he added. “I thought maybe they could be an inspiration to young people.”

He then set about connecting Yoo to contacts like Karen Park of Ten Communications, a marketing company focused on Asian American markets. From there, companies like Hyundai Motor America, Korean Air, Hite/Jinro, The Face Shop, LG mobile and the Korean Tourism Organization stepped in to sponsor the film.

Thanks to a grant from the Seoul Film Commission in 2008, Yoo was able to scout locations in Korea, affording her an opportunity to meet Kang Hye-Jung. “[During] our first meeting, she barely even said anything,” Yoo recalls. But after a subsequent meeting, Kang proved to Yoo she could handle the challenge of acting in an unfamiliar language. “She studied her ass off for a month prior to production,” says Yoo. During the course of filming, Kang married Korean Canadian rapper star Tablo, and her English greatly improved once they began shooting the second half of her scenes nearly a year after filming began. In fact, by the end of the shoot, she was improvising on set.

Tee admits, though, that the language barrier did present some challenges in building chemistry and rapport, made even more difficult by the fact that the romantic leads had to act to a blank computer screen since the characters were in a long-distance relationship. Overall, though, Tee gushes, “She did a beautiful, seamless job. She was a consummate professional, and I would love to work with her again.”

As an onscreen couple, the two play together well. Her effervescent, doe-eyed allure is on full display, and Tee is surprisingly vulnerable, given that he normally plays The Heavy in testosterone-fueled roles. “We had to soften him,” Yoo says, laughing. He was told, “You’re gonna have to lose 30 pounds, you’re gonna have to grow your hair out, and we’ re probably gonna have to shave your eyebrows.”

“Apparently, I have a built-in scowl,” Tee concedes. “We decided to trim down the top points of my eyebrows to soften the overall look.”

While Tee’s look was softened, the film’s humor certainly was not. It is unabashedly broad, brash and, at-times, certainly over-the-top, yet manages to never revel in stereotypes. “My main objective withWedding Palace is just simply to create feel-good entertainment that could be enjoyed by the widest possible audience,” Yoo explains. “I think there’s a lot of power in making people laugh.”

She drew inspiration for the film from Baz Luhrmann’s gaudy comedy, Strictly Ballroom, which exposed audiences to the arcane world of competitive ballroom dancing. An avid Woody Allen fan, she also has long admired his ability to make specific Jewish experiences universal. Similarly, Yoo hopes to introduce Korean culture to a wider audience. “It’s an entertaining entryway into a different world.”

Her Midwestern no-nonsense upbringing gives her faith that non-Asian audiences will also connect with the film.

“The typical Hollywood thinking is that some dude in the Midwest is not going to necessarily identify with an Asian character. I just actually don’t believe that because I grew up there. I just refuse to believe in that paradigm. That’s just not what my experience has ever been.”

Though the film, to be distributed in theaters nationwide later this year, ultimately aspires for crossover appeal, the distribution plan will first target pockets of large Asian American communities, Yoo said. She has examined the 2010 Census data and is encouraged by some impressive numbers like the 46 percent growth of the Asian American population since 2000, more than any other racial group. “Just looking at the numbers and where the population exists, the beauty of the population is that it’s very clustered into the top demographic markets,” she says. “So from a distribution strategy, it makes the job of putting the movie out there and getting it to the target demographic more cost-effective.”

Of course, getting Asian American moviegoers to rally around a film is a tricky business.

“The Asian American audience is far too diverse—ethnically, socially and politically—to expect it to rally around a single work or genre of works that may not necessarily reflect the perspectives of certain communities,” says Abraham Ferrer, co-director of the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival, in an email.

He says the Asian Pacific American community is certainly not an insignificant one, especially when you factor in the combined community’ s buying power and growing economic and cultural influence, but then, its “rapidly growing acculturation can also be seen as a double-edged sword.” Ferrer mentions how Korean American actor Sung Kang, shortly after completing filmmaker Justin Lin’s Finishing the Game, lamented how Asian Pacific Americans are perceived as consuming mainstream American products, including movies, in much the same way white audiences do. That’s why Hollywood does not necessarily see the importance in developing works by or about Asian Pacific Americans.

But the very fact that studios aren’t likely to greenlight a film like Wedding Palace is one of the reasons Yoo felt she had to do it without Hollywood’s blessing. “The American audience is ready,” she says. “And within the Asian American community, people are starving for something like this.”

Regardless of what happens at the box office, it’s hard not to see the completion of Wedding Palace as a victory. How many first-time directors manage to convince Korean Air to ground a 747 to allow her to shoot inside of it? How many directors—male or female—ever coordinate an international shoot with two different crews?

Moreover, veteran actor Stephen Park—who famously wrote a mission statement in 1997 denouncing Hollywood’s institutionalized racism—declared in a phone interview: “Wedding Palace is an expression of what I was [advocating for] in the mission statement—that we can be more inclusive in our storytelling. We can be more celebrating of many other people. Everybody I think recognizes that the film is unusual and also a celebration of Korean/Korean American culture and we haven’t seen a lot of films about Korean Americans, so that was really great to have this experience because it was rare.

“But hopefully there will be more of this kind of thing in the future. This is [Yoo’ s] first film, and I think it’ s been successful on so many levels.”

Whether success is defined by the awards the film has won (Best Feature Film and Best Cinematography honors from the Cine Gear Film Series Competition), the audience it eventually draws or just the sheer fact that it got made, Yoo and Tee are unequivocal in their gratitude. “The movie was made by the Korean American community,” Yoo acknowledges.

Tee adds, “If we didn’t have the support and influence of Koreatown, we couldn’t have done this movie. It was all community driven.”

Perhaps the list of things you need to make it in Hollywood should be expanded. You need moxie, grit, a bit of luck, a PowerPoint presentation…and a community to rally around you.

For the latest news on screenings, visit weddingpalacemovie.com.

This article was published in the March 2012 issue of KoreAm. To purchase a copy of this issue, click below.