By Sung-Min Yi Photographs by Elizabeth Kim

On June 28, 2009, President Barack Obama hosted a White House reception commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Stonewall rebellion, a police-raid-turned-riot considered to be the opening salvo of the gay rights movement. There, he reasserted his commitment on issues important to the gay community: a repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act; laws that address domestic partner benefits and hate crimes; a reprieve on the ban that prohibits HIV-positive travelers from entering the United States.

“And finally,” he said, “I believe ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ doesn’t contribute to our national security.” Obama had promised to repeal the law, which requires the military to fire any openly gay, lesbian or bisexual service member. Cheers broke out from the crowd.

Two days later, a military review board in Syracuse, N.Y. recommended that the Army discharge 1st Lt. Dan Choi, 28, a West Point graduate, Arabic linguist, Iraq war veteran, Christian and homosexual.

“I was not invited,” said Choi of the Stonewall reception. “It would have been a nice cocktail party, but I was too busy getting kicked out of President Obama’s military.”

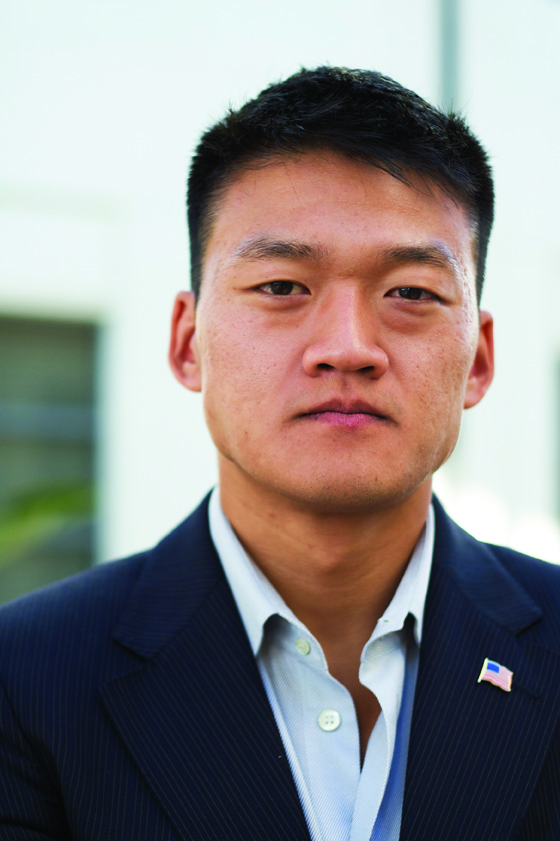

Choi with boyfriend Matthew Kinsey in New York.

Choi’s absence from such a high-profile event is surprising. “I am gay,” he announced on nationaltelevision in March, becoming one of the first soldiers on active duty to invite discharge under the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy (often referred to as DADT) since Obama became president. The act transformed him into one of the most prominent gay activists in the country. Once a soldier in southern Baghdad, Choi now crisscrosses the United States, making appearances, leading parades, giving speeches and courting the media. At one point, he says, he did 18 straight hours of interviews.

“Right now, the poster child is Dan Choi,” said Randall Henderson, a member of USNA Out, an organization of gay and lesbian U.S. Naval Academy alumni.

Yet Choi is only one example of the many young veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who, upon returning, have become vocal critics of DADT. These veterans reflect the views of their civilian peers, who are shifting public opinion toward greater acceptance of sexual diversity. Gay marriage is now legal in six states, something unfathomable in 1993, when DADT became law. Further, military leaders have grown increasingly critical of the policy. Almost 13,000 service members have been expelled under DADT, and with the U.S. government waging two wars, resources are stretched thin even without the discharge of highly trained Arabic-speaking soldiers like Choi.

On May 5, 2nd Lt. Sandy Tsao, a U.S. Army officer based out of St. Louis, received this handwritten note from President Obama, written in response to a letter from Tsao asking him to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” under which she was discharged.

Now, with a new commander-in-chief in the White House who has repeatedly pledged to repeal the policy, there is a growing sense that the days are numbered for Section 654 of U.S. Code Title 10. Yet Choi’s military future remains unknown. “I’m still in the military. I raised my hand to serve. That’s it,” he said. He’d rather be over there, in Iraq, helping to foster the fragile peace that has blossomed. But the way it’s turned out, the battle is closer to home.

***

The crowd roared as Choi took the podium at “Meet in the Middle,” a May 30 rally in Fresno, Calif. He raised his fist in solidarity, standing ramrod-straight in his blue sports coat, American flag pin affixed to his lapel, his West Point class ring on his right hand. As the applause died down, someone shouted, “Love is worth it!”

The phrase is a key refrain in Choi’s fiery rally speeches, one that underscores his motivation for coming out so publicly, one he urges the crowd to chant along with him at the rhetorical peak of his address. “It’s the reason I got out of the Army,” he said. “So I could grow through an intimate love relationship.”

Predictably, Choi’s fame has complicated matters at home. Choi had come out to his family last November, but his parents were still livid when they first saw Choi’s story in a Los Angeles area Korean-language newspaper earlier this year. “It caused a huge blowup,” said Grace Choi, 25, Dan’s sister.

Choi is the son of a minister who moved the family around as he spoke at Korean churches throughout Southern California. The household’s Korean Southern Baptist ethos made it difficult for Choi to confront his sexual orientation, which he became aware of during grade school. “I remember crying my eyes out at [church] retreats because I just wanted to pop a boner for Michelle Pfeiffer the next morning,” he said. “That’s the strangest thing to be praying about.”

The Southern Baptists decry homosexuality and maintain a “hate the sin, love the sinner” stance, an attitude that has wounded Choi deeply. “Those aren’t the lessons of God,” he said. “The saddest thing is that established religion has robbed gays and lesbians of faith.”

Throughout his upbringing, Choi stayed active in school and church activities, determined to keep his sexual orientation a secret.

His list of high school extracurriculars could belong to any overachiever’s: student body president, varsity swim team, marching band drum major. During his senior year, after watching Saving Private Ryan, he decided to attend West Point. At the time—in 1998—the possibility of war seemed remote.

All that changed when terrorists struck New York City’s Twin Towers during Choi’s junior year at the prestigious military academy. He had already been studying Arabic, but 9/11 spurred him to become fluent. And so, he became one of the eight soldiers from his graduating class who majored in the language.

Choi’s eventual assignment: A tour of duty in the infamous “Triangle of Death” in southern Baghdad, Iraq, in 2006.

During his tour, Choi often served as a bilingual liaison between local leaders and the U.S. Army. He would quiet angry crowds after residences had been bombed, and he once recited a poem at a meeting for a Baghdad neighborhood governance council.

He had also studied engineering at West Point, and led infrastructure reconstruction projects in Iraq. The experience was so fulfilling that “I actually wanted to live there,” he said. When Choi completed an extended tour of duty in 2007, he transferred to active duty with the New York National Guard and planned to go on another tour as soon as he could.

Then he met Matthew Kinsey, 45, an executive for Gucci. They quickly became close, and started dating. Kinsey joked that his Gucci connections would be “so perfect for your Korean relatives.” Choi, whose army training had made him accustomed to wearing the same shirt every day, finally had someone to dress up for. And, for the first time in his life, he was in love.

Naturally, he wanted to talk about it. But Choi, when sharing with his fellow soldiers, had to be careful with his pronouns. He had to refer to Matthew by a code name: Martha.

The situation was classic DADT. Proponents of the law generally cite a homosexual’s negative effects on military discipline, troop morale and unit cohesion. Choi felt the irony of the old arguments, as he found his own ability to be part of the unit compromised by his need to lie. “It’s not a matter of not asking and not telling,” said Choi. “It’s a matter of…being secretive, ducking and hiding, being completely terrorized,” he said.

So, in March 2009, Choi came out publicly on the pages of the Army Times and on MSNBC’s The Rachel Maddow Show. He also co-founded Knights Out, an organization of gay and lesbian West Point alumni. And as he began his life as an openly gay man, he knew he was risking his career for love. But, it was worth it.

“When you have that commitment and sacrifice and growth and completeness, it’s not worth it to lie about that,” Choi said. “So it becomes worth it to let people know and to share that. It’s something that makes you a whole person.”

But a month after coming out, Choi received his discharge letter, giving him two options: to accept an honorable discharge, or to plead his case before a military review board. He chose the latter. Choi also wrote a letter to Obama, asking for a reprieve. The message went unanswered, which was surprising given the president’s handwritten note in response to a similar letter from recently discharged 2nd Lt. Sandy Tsao (see previous page). Choi went before the board bearing a petition with 424,343 signatures of support.

The board still recommended that the Army fire Choi. He now awaits final word from the 1st U.S. Army commanding general, according to Eric Durr, director of public affairs for the New York National Guard. There is no way of knowing exactly when the decision will be made, Durr added, and until then, Choi remains an officer with the Army.

While he waits for an answer, Choi is living with Kinsey in New York. He is currently not speaking to his parents. For six months, he lived with them, hoping that his presence would eventually persuade them to accept their gay son. Instead, they condemned his life “every single day,” said Choi. His father did, however, tell his sister recently: “It’s OK if you support your brother and everything, but you should still go to church.”

The lieutenant called it a promising sign that his parents will eventually choose family over “misused Bible verses.”

***

Choi was only 10 years old in 1991, when Gulf War veterans, many of whom had been out to their units, were returning home and facing expulsion under the military’s strict ban on homosexuals. Then-Governor Bill Clinton campaigned on a promise to allow gays to serve, and he tackled the issue early during his first presidential term.

He soon met vigorous opposition. Military officials, including then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell, spoke of the need to keep homosexuals separated from the unit because of their negative effect on good discipline and order. Many appeared to embrace the argument, as a 1994 Wall Street Journal-NBC poll found that only 44 percent of respondents thought that openly gay Americans should be allowed to serve in the military.

Clinton accepted DADT as a compromise. Instead of an outright ban, the military wouldn’t “ask” questions about sexual orientation. Gay Americans could serve so long as they kept their sexual orientation under wraps.

Since then, public and military opinion has shifted toward greater acceptance of homosexuals. A 2009 Washington Post-ABC News poll found that 75 percent of respondents thought that openly gay Americans should be allowed to serve. A 2006 Zogby poll revealed widespread tolerance among veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq, with nearly three in four military personnel indicating that they were “personally comfortable in the presence of gays and lesbians.” And late last year, more than 100 retired military leaders signed a letter urging Obama to repeal DADT.

Obama recently laid out his plan for fulfilling his campaign promise by pursuing alternatives to full enforcement of DADT while waiting for Congress to finalize a bill that would repeal the law.

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates elaborated on the first part of the strategy, recently expressing a desire to find “a more humane way to apply the law,” particularly in cases that find “third parties trying to harm someone who may be gay and in the service.”

Both houses of Congress are working to present Obama with the legislative repeal he seeks to sign into law. This fall the Senate Armed Services Committee will hold hearings on DADT. It will be the first formal re-assessment of the Clinton-era policy since Congress passed it into law more than 15 years ago.

Meanwhile, the Military Readiness Enhancement Act, which would do away with DADT, works its way through the House of Representatives. U.S. Representative Patrick Murphy (D-VA), an Iraq War veteran, recently became the new sponsor of the bill, “lighting a fire” under efforts to get it passed, according to Kevin Nix of the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network, an organization dedicated to ending discrimination against military personnel affected by DADT. At the time of this writing, the bill had 165 co-sponsors, approaching the 218 that would guarantee a majority. SLDN is lobbying for more sponsors, and Nix said, “We’re very interested in getting this done over the next year.”

White House press secretary Robert Gibbs gave a looser timeline, predicting DADT would be repealed by the end of Obama’s first term.

***

On a recent July night in Los Angeles, Choi spoke at a screening of Silent Partners, a documentary about the often stressful effects of DADT on soldiers and their same-sex partners. Julianne Sohn, another Korean American Iraq war veteran discharged under DADT, was also a panelist.

“We have our own DADT policy in our community,” said Sohn, of Korean Americans. “But if people do come out, it humanizes gay people. You realize: They’re my brother, they’re my cousin, they’re my daughter or son.

“I actually had relationships while I was in the military on active duty,” added Sohn. “And so, for me, this policy is very personal and very much an affront to a person’s basic right to love somebody. Can you imagine spending an entire week—how about four years—not talking about your spouse to somebody else?”

The event drew its share of Asian Americans; one of them, Harold Kameya, a member of the Asian Pacific Islander Parents, Families & Friends of Lesbians and Gays, spoke admiringly of Choi’s activism. “Especially when Koreans [and] Asians are supposed to keep quiet and not stick their heads out, you have a person so brave like Lt. Choi [speak out],” said Kameya, whose daughter came out to him and his wife, third-generation Okinawan Americans, in 1988.

Like most soldiers discharged under DADT, Choi insists that he would re-enlist if given the chance. But at this point, it’s difficult to see him fitting in as just another soldier, just another officer. He seems to have come too far from his original trajectory.

Though Choi is clearly running with his celebrity at this point, wielding it to advance his cause, his fame indeed, has come with costs. He has risked his career, isolated himself from his parents, and placed upon himself the burden of spokesperson—a role that he, as a military man, must still learn to reconcile.

“It’s a little difficult for soldiers to call themselves activists,” Choi said, “particularly because we’re told: do not protest. And we study and practice and train on how to quell the riot. [But] ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ goes against all our values. All we’re saying is: don’t lie and don’t hide. All I did was refuse to lie. How is that activism? Why is that extraordinary?”

The movement to abolish DADT, which Choi now represents, is already echoing past battles for equality. In 1981, the Department of Defense published a study regarding gays in the military that made reference to the debate over the racial integration of the military earlier that century:

“The order to integrate blacks was first met with stout resistance by traditionalists in the military establishment. Dire consequences were predicted for maintaining discipline, building group morale, and achieving military organizational goals.”

None of those predictions came true.

Additional reporting by Julie Ha.