Most people have some awareness that a large chunk of the Transcontinental Railroad was built by Chinese immigrants in the years following the Civil War. Beginning in Sacramento, the Central Pacific Railroad stretched 690 miles eastward across the harrowing Sierras and blistering deserts to join the Union Pacific Railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869. Connecting the East and West coasts changed the course of the country’s destiny, but the more than 20,000 “Railroad Chinese” who laid the groundwork for such a transformation are almost never recognized by history. Their vast contribution to the construction of the railroad was, at best, reduced to a passing comment in history books and, at worst, “repaid” by exclusionary immigration policies that banned Chinese immigrants from becoming Americans for decades.

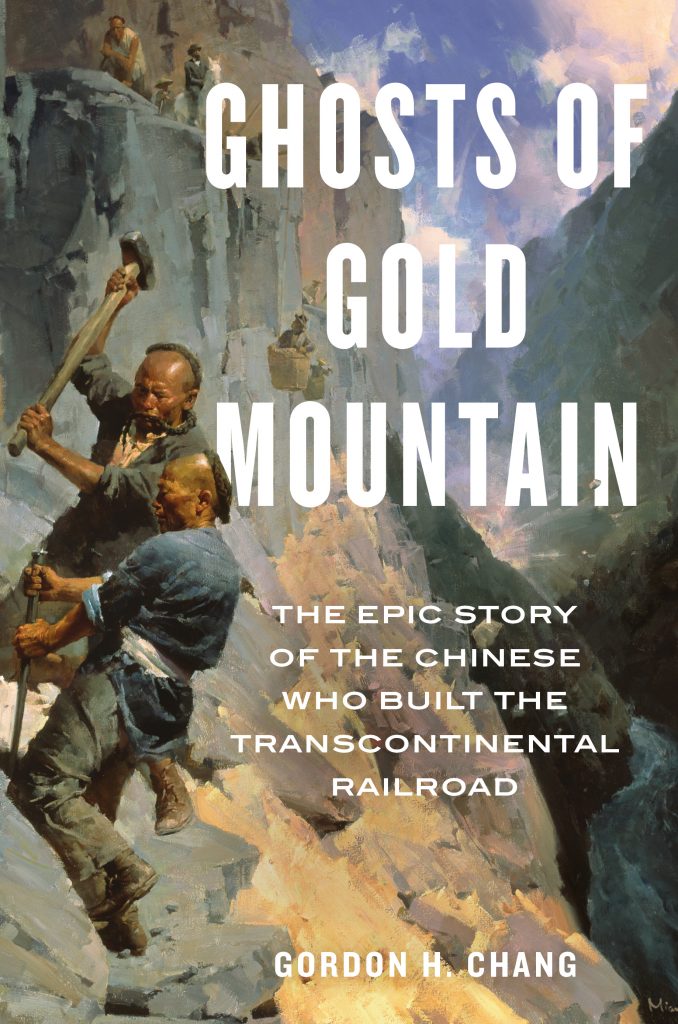

That’s where Gordon Chang comes in. “Ghosts of Gold Mountain” is a feat of scholarship that aims to refocus the faces and stories of the Railroad Chinese. Chang sets his sights on the men and women who made up 90 percent of the Central Pacific Railroad’s workforce and helps his readers see them as real people. One of the first orders of business for Chang is to debunk the common misconception that these Chinese immigrants were slaves forced to lay down tracks across treacherous terrain and blast through formidable mountains. While it’s true that the Railroad Chinese worked on the tougher parts of the tracks, most, if not all, immigrated to America of their own free will. Most were young Cantonese men who left their farming villages that had been plagued by famine and political instability, to seek their fortunes in California, known to them in the 19th century as Jin Shan, or “Gold Mountain.”

Drawing from a wealth of sources like magazine and newspaper articles, payroll books, audio recordings, diaries, work rosters and timesheets, Chang’s “Gold Mountain” reads like a novel, biography and a history textbook all in one. Which is not to say that it’s a bad mix. One minute, readers can read about how a teenager felt his stomach twist into knots as his ship docked in San Francisco harbor, and then be regaled with how inconsistencies in Romanized Chinese surnames made it tricky to determine how many Chinese men actually lived in a certain area. At times, the abrupt shifts can feel disruptive, but the sheer amount of detail that Chang draws from such lean sources is what allows the author to claim his work as “epic.”

“Gold Mountain” doesn’t just resurrect the forgotten legacy of the Railroad Chinese, it also reminds us to remember the “ghosts” that surround us today. Immigrants are still doing the brunt of the menial, dangerous, unwanted but necessary work in America, and often without fair pay, benefits, insurance or recognition. They may be our own cousins, aunts, uncles or parents. Chang’s “Gold Mountain” isn’t just another detailed history of 19th-century Chinese immigrants, but it serves as an important historical and cautionary tale that sheds a sobering light on our current immigration crisis. Through his retelling of the almost-forgotten story of the Railroad Chinese, Chang urges readers to recognize the industrious spirit of American immigrants before they are turned into ghosts.

This article appeared in Character Media’s May 2019 issue. Subscribe here.