by Eugene Yi

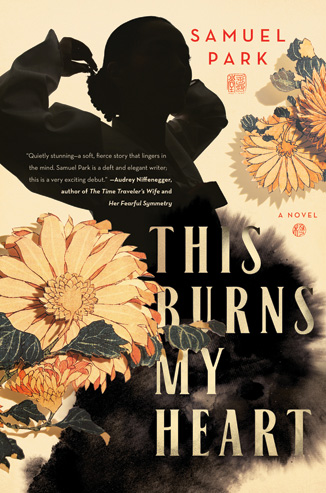

Author Samuel Park is a “man vs. society” type of writer; his first book dealt with a young closeted scholar in 1940s New England struggling with his sexuality. His newly released book, This Burns My Heart (Simon & Schuster), follows the story of a young Korean woman named Soo-ja as she struggles to escape the prescribed destiny of her gender during the 1960s, a time of political unrest, economic instability and cultural upheaval. It’s a tale inspired by his own mother and her vivid recollection of a handsome suitor who asked her out the day before her wedding to Park’s father.

KoreAm’s Eugene Yi caught up with the 35-year-old author (and former KoreAm contributor) while he was promoting his book in Los Angeles last month. Park revealed that he learned some surprising things in talking to other Koreans about the novel’s plot.

There’s an element of estrangement from society in both your novels. Does any of that come from first growing up in Brazil, then moving to America in your teens?

People who immigrate, in my opinion, are people who have some kind of fantasy about what their life could be like. I almost forced my parents to immigrate. When we were in Brazil, I was 14, and my parents were kind of on the fence about it. My grandfather had moved here, I think, in ‘84, and it was kind of on the radar, and I insisted and said I really want us to move to America because I had this kind fantasy vision of what America would be like.

It must have created a certain relationship to American pop culture. You mentioned in other interviews your love of 1950s American films.

When I grew up in Brazil [in the 1980s], … things like rule of law didn’t really apply there. It was a time of hyperinflation. You’d go to a store to buy something, and they would change the price. Everything felt fluctuating and unreliable. The money you had in your pocket suddenly didn’t have value a day later. Even as a teenager, I longed for a place where there was more security about the way you go about your life, where you could plan for your future. And so when I would be watching [American] movies, where people experienced the comforts of democracy, and it boils down to human relationships and how they treat each other, it seemed so nice.

You are still an ardent watcher of Brazilian soap operas. How do they differ from American ones?

They’re very unlike the American ones, but they’re very similar to the Korean dramas. They typically center on one or two families in conflict with each other, and they deal with class, where one is wealthy and one is poor. There’s always this wish fulfillment fantasy of marrying into a rich family—a common fantasy for many Brazilians. That’s reflected in the book, where Soo-ja really wants to make more money. My editor really didn’t understand that. I feel like in America, it’s so taboo to talk about class. When someone wants to marry into money, they’re called a gold digger. But that’s what all of those shows were like in Brazil and in Korea.

As you were doing research for the book, what surprised you the most?

Things that I thought were very specific to my family turned out to be rooted in some kind of historical event—even the central plot of the book … which was inspired by the story of my mother getting asked out by a stranger the day before her wedding. I was hanging out with James [Ryu, publisher of KoreAm Journal], and he said, “Oh, that’s funny, my mother tells me that same story.” And then I did a [reading] in Los Angeles, and one of the women in the audience said the same thing! And that moment kind of clicked. This is a common thing for women of that generation to believe in—the myth of that different life—because being a Korean woman of that generation required so much pain that you have to comfort yourself by thinking of this other life.

What did your mother think of the book?

I told her the plot of the book, and she just started laughing. I think she was really amused that I had taken the contours of her life and turned it into a high-class soap opera. It’s funny because I invited her to come to a reading, and she said, “I don’t want to go because I don’t want to ruin people’s sense of what the characters look like.” I thought that was cool.

This article was published in the September 2011 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today!

[ad#graphic-square]