Over the years, KoreAm has documented the impact of the 1992 Los Angeles riots on ours and other communities, and urged an understanding of lessons learned. As we count down to the 20th anniversary next year, charactermedia.com will be running a riot article, image or testimonial in this space every week until April 29, 2012. Some will be taken from our pages, while others will be excavated from our own personal archives.

We welcome your submissions—first-person memories (no word limit), pictures, poems and (photographed/scanned) artifacts—for this project, too. Please email them to julie@charactermedia.comwith the subject line ‘Riots Spot’. Many of us were mere children in 1992, but 19 years later, we have voices. We can speak now.

This article appeared in the April 2007 issue of KoreAm.

Revisiting The Scene Of The Crime

This former reporter who covered the 1992 riots and the events leading up to it reveals a truth much more nuanced than the “black-Korean conflict” headlines of that time.

by Richard Fruto

I was a reporter at the English-language Korea Times Weekly in Los Angeles from late 1990 to early 1993, and I covered the 1992 riots and the aftermath. I also reported on the events that led to the riots, starting with the shooting of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins by Soon Ja Du in March 1991.

As a reporter at the Korea Times, I had what my former editor, K.W. Lee, would call a worm’s-eye view of those events, and as the only non-Korean on the staff (I am Filipino American), I also had an outsider’s view from the inside. What I witnessed was a story that was not as straightforward as the perception that most people have of those events based on what they read and heard from the major media outlets.

Much has been written about these events in the media and academic circles. Yet most of these accounts, retrospectives and commentaries tend to paint the matter in broad terms. For example, most accepted the notion about tensions between Korean immigrant shopkeepers and African-American customers, who accused the former of rudeness, clannishness and exploitation, and described them as newcomers and outsiders who went in and did business without giving back to or hiring from within the community.

These stories of conflict between Korean immigrant merchants and their customers generally ignoredthe details. The absence of these details unfairly stereotyped each and every Korean immigrant who brought enterprise to the poorest neighborhoods in their own quest for the American Dream.

In my opinion, mainstream TV reporters caused the most damage. They often played into the hands of street agitators and boiled it down to a problem blamed on rude merchants.

Few question that some merchants were rude. Indeed, I heard many Korean Americans joke that Koreans as a people are ruder than other ethnic groups. But from my experience as a reporter at the Korea Times, I came away with the impression that only a minority of merchants treat their customers this way. There were many who co-existed peacefully with their customers. My impression was based on numerous interviews with merchants and customers over 29 months. It was an impression wildly at odds with the image of race relations that came out at the various news conferences on the subject that I attended during that time.

More often, the mainstream media failed to make a distinction between the activists who organized the store boycotts and the customers who patronized the stores. The 1991 boycott of Don’s Market in Hawthorne, a small working-class city south of Los Angeles highlighted this distinction. On December 14, 1991, Wha Young and Soon Ye Choi’s market became the target of another boycott by African American activists after a 12-year-old girl claimed Mr. Choi beat her up. Mr. Choi had accosted the girl after suspecting her of shoplifting. While the Hawthorne city attorney’s office filed charges against him, the girl was also charged with petty theft.

The boycott ended after Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley’s office and Korean American leaders protested that African American leaders had agreed two months earlier to mediate disputes to avoid future boycotts. But even if boycott organizers had not called off the protest, the store’s customers apparently would have fought them all the way. About 200 people in the neighborhood signed a petition in support of the store during the boycott.

According to Mrs. Choi, her customers often quarreled with the picketers. The Rev. Ricardo Wright, a black minister, signed the petition without hesitation. Other members of his family did the same. According to the Wrights, the demonstrators who picketed Don’s Market harassed them, uttering racial slurs to make them mad. In turn, just to make a point, Wright shopped at the store as often as he could.

“We were for the store because it wasn’t right what they were doing,” Wright said. “If [Choi] was wrong, that’s up to the courts to decide. Nobody appointed [the protestors] to speak for me.” The boycott annoyed white, black and Latino neighbors from the moment the pickets went up.

According to Wright’s daughter Josephine, nobody in the neighborhood joined the picket line.

Don’s Market is one reason I think relations between African Americans and Korean Americans in the early 1990s were not what they were billed to be. Even Tae Sam Park, whose store was also targeted in a boycott earlier that summer, had some support from his customers, though not enough to prevent the boycott from shutting it down.

According to police, Park shot Lee Arthur Mitchell because the latter allegedly was trying to rob the store and Park thought Mitchell was armed. No charges were brought against Park.

But many African Americans believed Park had shot Mitchell in cold blood, just as they believed merchant Soon Ja Du had done to 15-year-old customer Latasha Harlins in a tragic 1991 store shooting that set off a storm of controversy and media scrutiny. The boycott of Park’s market, John’s Liquor Store, drew media coverage from the time it began in June until it ended in October, when the Korean American Grocers Association agreed to close and sell the store.

One month into the boycott, Evelyn Smith, an African American neighbor, still shopped there. “I’m going to keep on buying,” Smith said. “I don’t know about the incident you all are talking about, but I do know I’ve been treated good here, and I’m going to keep on coming as long as they [are] good to me.”

Many Korean American merchants who lost their stores in the riots also received that kind of neighborhood support when they later sought to rebuild. Neighbor after neighbor testified in support at the Planning Commission hearings during this rebuilding process. I witnessed the outpouring of support when I covered the Planning Commission hearings while I was still a reporter at the Korea Times and later as a reporter for a wire service covering Los Angeles’ City Hall.

As a reporter at City Hall until 1995, I understood the odds that these merchants faced in their applications for permits to rebuild. More often than not, they were opposed by the Community Coalition for Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment, an influential group lobbying against the proliferation of liquor stores in the inner city.

Moreover, some planning commissioners were predisposed to vote against the rebuilding applications, despite findings from the city attorney’s office that no merchant could be denied permission to rebuild. Nonetheless, it was clear that the people of South Los Angeles, including African Americans, did not speak with a united voice against the Korean immigrant merchants.

In December 1992, merchant George Chung received unanimous approval to reopen his store from the Planning Commission after residents presented overwhelming testimony in his favor. Chung even won the votes of two commissioners who usually toed the Community Coalition line.

In at least one other case, the merchant and the residents supporting him were outraged because the Community Coalition brought in people from outside the neighborhood to testify against the store. Just as in the boycott in Hawthorne, it was people from outside the neighborhood — in another time, they’d be called “outside agitators” — who made trouble for the merchant. When I speak about neighborhoods, I don’t mean South Los Angeles as a whole. I mean the cluster of four, 12 or 16 blocks that make up a store’s customer base.

Grocers in South Los Angeles wanted to rebuild because they said they had no choice. One reason is they had developed a customer base.

If their customers hated them, does anybody think the merchants would have gone back, especially after the traumatic destruction of their slice of the American Dream in the fiery devastation of the riots?

Even in the mainstream media’s coverage of the riots, there were stories of residents helping merchants defend their stores. In some cases, neighbors called store owners at home to warn them that their shops were being looted. I heard some of those stories myself in numerous interviews with merchants. At L.A. Slauson Swap Meet, a record store clerk said his African American friends in the Crips warned him about impending trouble when the verdicts in the Rodney King state trial were read in April 1992.

They warned him, not threatened him.

Even some merchants said the public has misperceived the state of relations between African Americans and Korean Americans during that time. Sung Ho Joo, a grocer who lost it all in the riots, tried to make that point in a news conference in December 1992 when the results of a survey of riot victims was released.

“It’s not as bad,” Joo said. “Just some people.”

Few apparently listened.

In a community town hall meeting at the Los Angeles Times in 1991, Kenneth Thomas, then CEO of the black-owned Los Angeles Sentinel newspaper, said tensions between the two ethnic groups were “media-exacerbated, if not media-created.”

At the same event, Gina Rae, a member of the Latasha Harlins Justice Committee, said, “I do not see the racial conflict that the media constantly puts up.”

Again, few apparently listened.

In their coverage of relations between Korean immigrants and African Americans in South Los Angeles in the 1990s, the major media organizations largely focused on stories of conflict. These news organizations generally ignored stories of peaceful co-existence, uneasy or otherwise.

The few stories of Korean immigrants getting along with residents in South L.A. that filtered through the major media were generally mentioned only in passing, in a sentence or a paragraph at most. Unfortunately, in a world before blogs made an impact in challenging the major news media’s version of events, the mainstream media was the primary storyteller. Its stories became part of mainstream culture and shaped society’s understanding and perception of events.

But I know relations between Korean immigrant merchants and their customers in the inner city in the 1990s were more complex than the major media outlets made them appear. I spent enough time in the ‘hood covering the story to know that it was not so black and white.

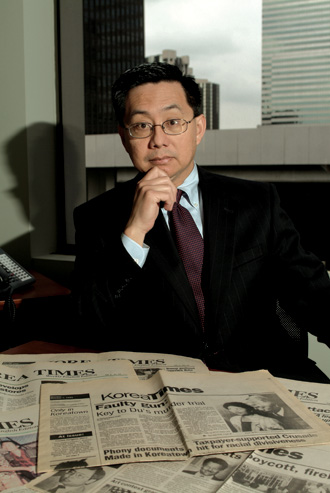

Richard Fruto, a former reporter for the English-language Korea Times Weekly and City News Service, is an attorney based in Los Angeles. His testimonial was adapted from an essay written for the “Children of Sa-i-gu” oral history project headed by Fruto’s former editor, K.W. Lee.