By Kathleen Wentz

It’s that all-too-familiar immigrant tale of Asian families who journey thousands of miles from their home seeking a better life and quality education for their children. But the story of more than two dozen Asian immigrant students in Philadelphia took a bitter turn last month, when they became victims of targeted, race-based beatings by their peers.

On Dec. 3, 26 Asian students were attacked and beaten by schoolmates at South Philadelphia High School. It was far from your average schoolyard brawl.

The violence began the day prior, when a Vietnamese student was jumped by 14 students across the street from the school, according to news reports. The next day, a group of students began searching classrooms for Asians—both male and female—to attack, according to victims’ accounts. One student was walking to the cafeteria with two friends when someone ran up from behind and hit him in the head. His friend was pushed to the ground, punched and kicked. According to student testimonials, some were attacked in the cafeteria. Others were jumped after school across the street. Seven of the victims were treated at a local hospital.

It was unclear what motivated the attacks. One student told local media it was revenge after a group of Vietnamese high schoolers jumped an African American student the week prior. Most of the attackers in the Dec. 3 incident were identified as African American. Yet news accounts and testimonials from the victims indicate that the violence against Asian students—primarily recent immigrants from China—has long been a problem at the school. And while administrators were aware of the issue for at least a year, students and Asian American community groups say the officials neglected to implement any meaningful changes to curb anti-Asian sentiment and physical attacks. Some Asian students said that certain school employees were even complicit.

“Violence is [being] condoned in this really corrosive culture,” said Helen Gym, a member of the Philadelphia-based Asian Americans United, a nonprofit whose mission is to build leadership in local Asian American communities. She has worked with school officials since last year on this issue. “It’s completely okay for staff members to mock students for the way they dress, for the way they talk, for the way they look, like calling kids ‘Bruce Lee,’ ‘Dragonball,’ ‘Yo Chinese,’ to things as dramatic as not filing incident reports when [Asian students] feel they’ve been harassed in the schools.”

In testimonials released by Gym’s organization, one Asian youth who went by the initials “Y.Z.” said that while students were fighting in the lunch room, “the lunch lady did not do anything to stop them and went around cheering happily.”

Immediately after this latest episode, Gym says district officials failed to conduct a full investigation and simply suspended 10 students (six African American and four Asian) “with intent to expel,” though Gym said she wasn’t sure what that meant. “It’s been a week since the incident and many of the students haven’t been contacted by the district,” she stated in early December. “They haven’t even called to ask about their well-being.”

She also decried the fact that officials downplayed the extent of the attacks and denied they were racially motivated.

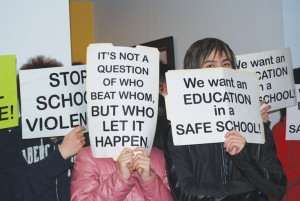

As a result, many Asian students decided to boycott school—a gutsy act that propelled the youth into the media spotlight. During that time, school officials held meetings and promised to ramp up security measures and form a task force on racial and cultural harmony. An apology from principal LaGreta Brown didn’t come until Dec. 11—more than a week later. Gym said these measures were “too little, too late.”

“They still don’t address the root causes of the violence,” the activist said of the district’s efforts. “If race is something you can’t talk about, but [is something] that continues to get abused on a regular basis, then we’re not going to get anywhere. The school kept saying this was a minor incident—an after-school brawl. That’s not true. One of the students who was injured and bruised was beaten up in front of adults.”

In a released statement, Wei Chen, a student who has emerged as a leader in the movement to stop the anti-Asian attacks, said that district officials have long known about the violence, but failed to do anything about it. In October of 2008, about 30 students attacked Chen and about five other Chinese students in front of the school. After that incident, Chen formed the South Philadelphia High School Chinese American Student Association.

Though officials promised more security following the 2008 attack, Chen said the school never installedsurveillance cameras as promised nor made any other changes. Instead, he said, the violence is “getting worse.”

In fact, the problem is more widespread. Troubling violence toward limited-English-speaking Asian immigrants at Philadelphia high schools was the subject of a September 2009 cover story in the Philadelphia Weekly. The attacks—which include verbal harassment to large-scale brawls—prompted increased collaboration between community groups and the school district, and eventually led to the hiring of a new principal, Brown, at South Philadelphia High School. According to Chen, Brown stopped the practice of physically segregating by floors the English language learners, many of whom were Asian, from the rest of the student population.

But even before the most recent assaults, overall violence at the school was up 32 percent from last school year, according to district statistics. Latino immigrant students also have complained they’re being attacked.

An estimated 70 percent of the school’s roughly 900 students are African American, 18 percent are Asian, 6 percent are white, and 5 percent are Latino. According to the school’s website, about 72 percent of the students in the 2005-06 school year were from families eligible for free or reduced-price lunches. Citywide, about 73 percent of the population was considered low-income during this same period.

Notably, the immigrant population at the school, and in the area, has been rising in recent years. The demographic shift may help explain some of the friction.

As the Chinese and South Asian immigrant population ballooned in Brooklyn, N.Y., between 1990 and 2000, Asian students at Lafayette High School became the target of hate violence and regular bullying by their peers, as staff turned a blind eye, a U.S. Department of Justice investigation found. For several years, the New York-based Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund worked with the high school students to address the anti-Asian violence. In 2004, Lafayette entered into a Consent Decree and was ordered by the Justice Department to enforce anti-harassment policies.

AALDEF announced last month it would file a civil rights complaint with the Department of Justice against the Philadelphia school district for failing to address the violence against Asian immigrant students. “The severe, rampant and unchecked nature of the racially motivated attacks against Asian students at South Philadelphia High School far exceeds what I have seen,” said Cecilia Chen, a staff attorney with AALDEF, in a press statement.

The high school is considered a “persistently dangerous” school, a state-defined designation under the federal No Child Left Behind Act. The law allows parents the choice to transfer their children to a “safe” school in the area.

But as of press time, the students boycotting South Philly High agreed to return to school after 12 days, following a meeting with Superintendent Arlene Ackerman. Ackerman’s office did not return KoreAm’s calls. School officials have publicly stated that the district is continuing to probe the incident, and a police investigation is expected to result in charges. An outside investigator has also been hired to look into the case.

Meanwhile, both African American and Asian students at the high school are trying to squelch the notion that there’s widespread hostility between the two groups, and have cautioned against pigeonholing all black students. In his testimony, Chen said, “I have had lots of African American friends and they have helped me, and so I know that we are not enemies.”