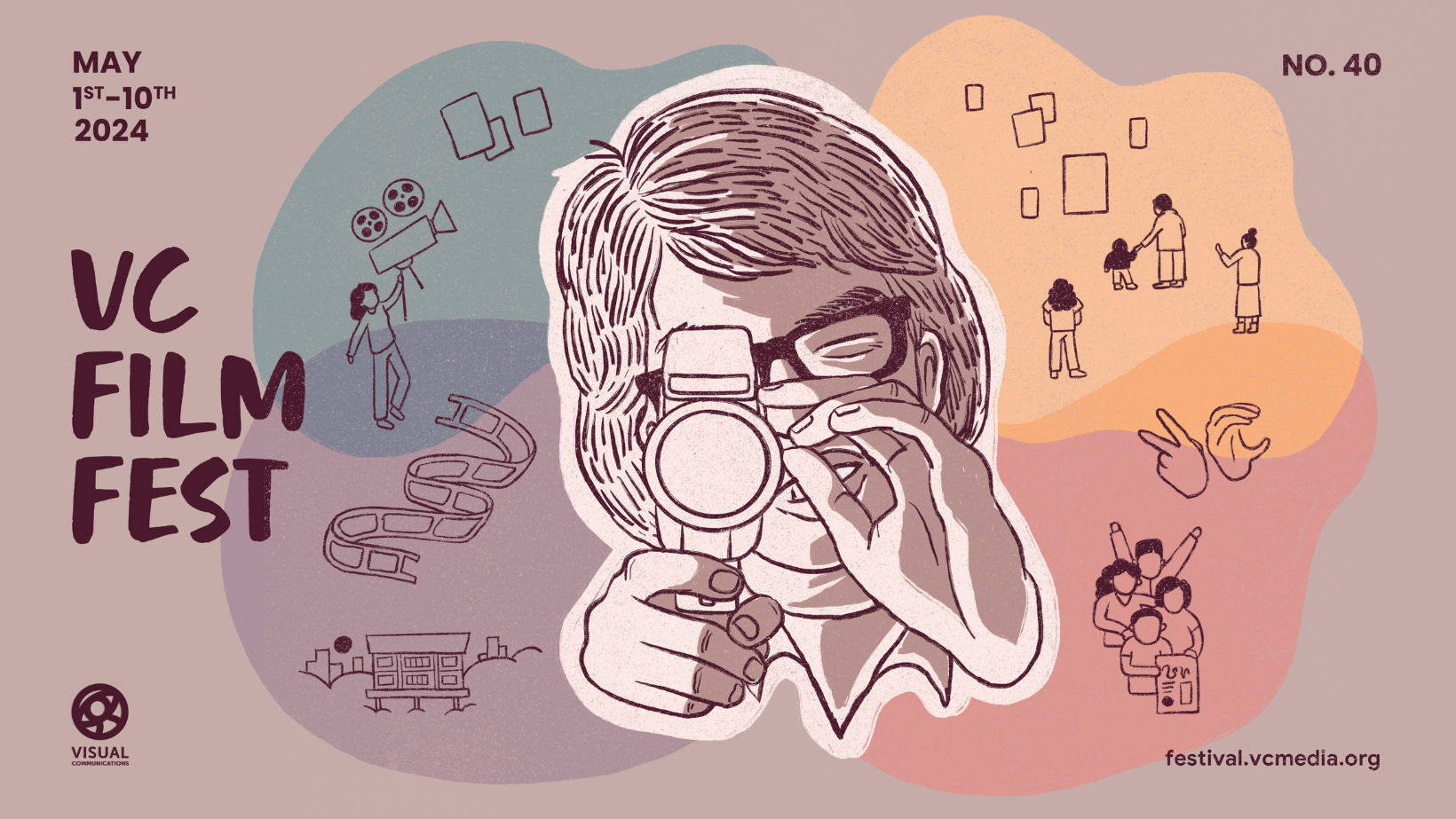

In the hustle and bustle of Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, the newly minted VC Film Fest (formally known as the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival) returned for its 40th year. The festival continues its longstanding tradition of platforming Asian and Pacific creatives with 150 projects — made up of documentaries, full feature films, animated programs and various shorts.

The 10-day festival, which took place from May 1 to May 10, welcomed API filmmakers from around the world to Los Angeles. It showcased different programs, panels and screenings (some projects were also available online) for festival-goers to enjoy. This year, in particular, the festival hoped to encourage audiences to support and consider participating with organizations that serve Black, Indigenous and other communities of color.

Plenty of films showed on the festival screens, from hard-hitting documentaries examining Chinese politics to introspective art films on family histories to feature films on the art of growing up and maturing. See what films captured the Character Media’s attention below.

The Armed With a Camera (AWC) Shorts Program

Text by Jasmine Nguyen

The program, which returned for its 21st year, is a fellowship for emerging Asian American and Pacific Islander filmmakers. This project allows the next generation of directors to experiment and hone their filmmaking skills. This year, the young creatives used the VC Archives to cover and feature various topics pertaining to their API identities and cultures. Read our reviews to see our favorites from this year’s batch.

Paula Kiley’s “Balik/Bayan” short tells the story of Manny Paez, the founder of Manila Forwarder, a balikbayan box (packages filled with various goodies from other countries that are sent back to the Philippines) company owner. The short recalls how Paez’s own childhood experiences with balikbayan boxes shaped his outlook on America and set him off on a course far from his home. Kiley’s use of colorful and snappy graphics along with Paez’s heartful narration make the film stick with audiences and mull over how sometimes it’s the mundane things in life that affect you the most.

“KE ALA” by Bryson Nihipali is a short film that features interviews with the director’s family living in both Hawaii and California. Throughout the film, Nihipali combines present-day interviews with old photos to piece together his family history and how his relatives spread across the diaspora keep in touch not only with each other but with their culture as a whole. Nihipali’s ability to merge VHS and high-definition footage brings an intimate touch to the film, and the honest conversations shared between relatives easily pull the viewers into this tight-knit family.

“Daughter of Guam” by Alfred Bordallo differs structurally from the other shorts offered in the program. Bordallo, a multimedia artist who also curated the Digital Camouflage art installation, took a more experimental approach to his short film. “Daughter of Guam” is a surrealistic take on a young CHamoru woman as she takes on her role as a fledging community matriarch. Bordallo uses a soft yet all-knowing voice for the narration along with eye-catching visuals, bringing an almost dreamlike trance over audiences and showing how an artistic eye can tell a grounded story.

Text by Jasmine Nguyen

For Yi Chen’s first documentary “FIRST VOTE,” the filmmaker focused on the Chinese American electoral organizing during the 2016 and 2018 midterm elections in the United States, exploring the diverse political background of Chinese Americans across the nation. For Yi’s sophomore documentary, she expanded her focus to a different political issue: Chinese dissidents within the States and the struggles they face fighting for democracy in their homeland. The 75-minute film follows three political activists, the first being one of the world’s most renowned Chinese dissidents, Juntao Wang, who was a primary organizer of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. The second is artist Weiming Chen, whose sculptures criticize the Chinese government and are constantly burned down and destroyed. Lastly, the film focuses on Chunyang Wang, an asylum seeker who was forced out of her home after the Chinese government took over to build high-rise buildings. The documentary uses intimate observational footage of the three subjects along with historic archival materials to create a suspenseful and eye-opening film that explores the intricacies of political activism and more.

Text by Caroline Yu

Director Erica Tanamachi‘s first feature-length documentary, “Home Court,” isn’t just an inspiring tale for female athletes and directors; it’s also a cathartic story of immigrant mother-daughter relationships. The film follows star basketball recruit Ashley Chea, a Cambodian American girl of immigrant parents as she makes her way through high school. We watch Chea as she attends her high-ranking private school — far-and-away from her home zip code — trains at an elite basketball camp, overcomes injury and paves the way to her dream college.

One of the central figures in “Home Court” is Chea’s coach, Jayme Kiyomura Chan, who recommended her as the subject for the project. Throughout the film, the audience watches as Coach Jayme and Chea’s relationship is put to the test by way of arduous basketball tournaments, college decisions and familial discord; however, even with all the cameras (hence added pressure), they stay as strong as ever. “Ashley and I were very close prior to filming; I don’t think that [the documentary] affected our relationship that much,” Chan said. “I am a pretty passionate and transparent person, so [Ashley] would’ve gotten the same version of me with or without the cameras filming.”

Of course, the relationship between Chea and her coach is just as important as another dynamic featured in the film. Chea and her mother, Lida, are sparingly shown together, but their somewhat strained bond is the punch that packs this film. The audience follows Chea through so much trial and tribulation regarding her sport, but her emotional journey with her immigrant parents — trying to grasp the sacrifices they made, the games they’ve missed and why, how they express their love and their laser-focus on her younger brother — is the real draw here.

Now, a year into college, Chea reflects on the film: “Looking back [on high school], I think that I would’ve wanted to see my friends, family and the people around me for who they are. Since my freshman year of college is wrapping up, I’ve learned to see people with a wider lens and realized that [those] around me are meant to be there, in my best interest. I wish that I would’ve seen that sooner.”

“Home Court” reaps its rewards onscreen and, judging by Chea and Tanamachi’s own words, offscreen as well — in fact, it’s a blessing that she landed on Chea as a subject, as Tanamachi first considered just documenting the history of the Japanese American basketball leagues that rose to prominence after the internment. Through that initial endeavor, she was connected to Coach Jayme, who recommended Chea and her story. The rest is now history. “My biggest takeaway was how close I became to Ashley, Jayme, their families and my crew throughout filming,” said Tanamachi. “It’s so crazy to realize we were just strangers four years ago. When production ended in November 2023, I felt more sad than relieved that it was over. I gave myself time to process and feel that sadness, and now it’s really exciting to be in this next phase of festivals together!”

Text by Caroline Yu

Director Zoe Eisenberg’s feature-length debut, “Chaperone,” which made its world premiere to rave reviews at the Slamdance Film Festival, is a cautionary tale based on a true inciting incident. In an interview with Pop Culturalist, Eisenberg explains that when she was 29-going-on-30, a high school student hit on her thinking she was his age. Eisenberg laughed it off and let him know he was far too young; but, she soon became obsessed with the idea of someone who would deceivingly go along with the misunderstanding. Enter the main character of “Chaperone,” Misha (Mitzi Akaha) — a directionless 29-year-old living in her late grandmother’s home and working the same theater ticketing job she’s had for the past decade.

The audience follows Misha as she meanders through life, turning down job promotions, doing everything but scoffing at her friend Kenzie’s (Jessica Jade Andres) peaceful domesticity, taking care of the frail family cat and, most of the time, having nothing at all to do. Misha’s existence is blasé — a non-event of her own doing; that is, until 18-year-old supermarket clerk Jake (Laird Akeo) mistakes her for a high schooler and asks her out. But, she doesn’t correct him; she says yes.

From here, “Chaperone” comes into itself as a coming-of-age tale contrasted by the fact that it is also a quarter-life crisis in action. Akaha does a fabulous job of imbuing Misha with a sense of complete metaphorical and literal loss, which helps the character come across as more empathetic at times instead of writing her off as completely irredeemable. Akeo aces the puppy-dog, high school jock archetype with flying colors. His performance balances Akaha’s, ensuring that the audience cannot become too comfortable empathizing with the troubled Misha.

The film has pacing issues at its close. Even for a character as flawed as Misha, there is a limit to how many all-is-lost moments one film can take; however, “Chaperone” ends on a solid note, leaving the audience questioning if our protagonist has learned anything at all. Who is to say?