By Kai Ma

It is widely believed that where California goes, so goes the nation.

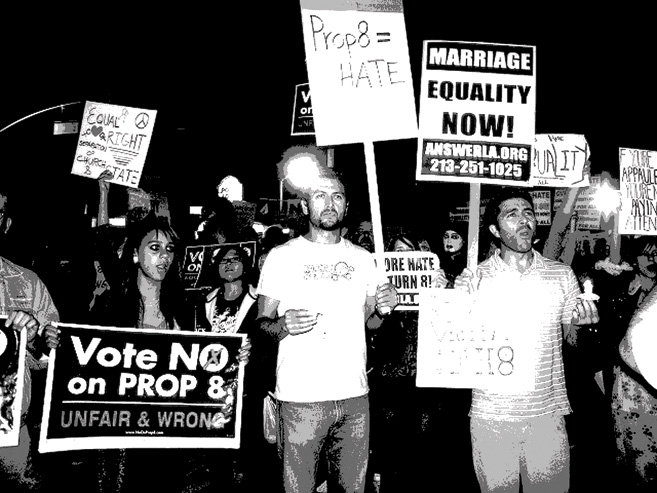

And so, on Election Day, Americans watched as California voters cast their ballots for Proposition 8, the statewide measure calling to eliminate same-sex marriage. Approved by 52 percent of voters, the amendment to the state’s constitution passed the next day, restoring the definition of marriage as a heterosexual union and thus, repealing the right of gay and lesbian couples to wed. Similar bans also passed in Arizona and Florida.

[ad#336]

In the days and weeks following the proposition’s passage, much has been made of the ethnic vote, especially the high African American approval vote (70 percent voted in favor, according to CNN exit polls), sparking a vitriolic gay-black divide, and triggering painful and arguably racist accusations that blacks were to blame for the proposition’s passage. Media commentators found contradiction in the fact that the same people who voted for the progressive-minded Barack Obama also voted for the ban, even though the president-elect has long said he supports partnership rights, but also favors defining marriageas between a man and a woman.

According to an exit poll conducted by the Asian Pacific American Legal Center, 54 percent of Asian Americans surveyed in Los Angeles County voted in favor of Proposition 8. The CNN exit poll listed the measure’s Asian American (statewide) support as 49 percent, consistent with the white vote, though the Asian sample size was likely small and weighted towards English-speaking voters.

Although voter breakdowns by ethnicity were not available as of press time, extensive interviews with Korean American Christian leadership as well as activists across Southern California suggest that Korean Americans were in large part supportive of banning same-sex marriage. In fact, months before the election, a number of Korean churches led an organized, efficient campaign that inspired thousands of Koreans not only to vote yes on 8 — but also to vote, period. Even progressive activists reported that many among their constituent base typically in favor of immigrant and minority rights were against allowing gays and lesbians to marry.

Watching from the frontlines was Paul Park, and he was stunned by what he saw. On June 17, Park became one of the first gay men to wed in California after the state Supreme Court legalized such unions. “I didn’t think Prop. 8 had any chance of passing,” he says. “It was a very difficult morning to confront.”

Park admitted he, too, was taken aback by what he called a “very strong” ethnic vote in favor of the ban. He said while reading some Korean blog posts before Election Day, he was hurt by the fear he sensed in the measure’s backers.

But James Pak, the Korean liaison to the Yes on 8 campaign and a member of the Mormon church, was not at all surprised by the level of Korean proponents nor the outcome. “Koreans [are] strong supporters of defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman,” he says. “We are a family- oriented culture.”

[ad#336]

Merging of Church and State

This perceived high level of support for the marriage ban probably says more about these Korean Americans’ identity as Christians than as Koreans, says Ian Kim, a campaign director for the Oakland-based Ella Baker Center for Human Rights.

After all, for many, marriage is not only a very personal issue, but a religious one. One study estimates that some 80 percent of Korean immigrants attend church, and it’s no secret Proposition 8 was heavily backed by religious organizations. According to the Los Angeles Times, campaign-finance data andpublic records were used to estimate that members of the Church of Jesus Christ and Latter-day Saints raised more than $20 million in donations for the Yes on 8 campaign. Days before the election, thousands of churchgoers of all racial and ethnic backgrounds flooded Qualcomm Stadium in San Diego for a 12-hour prayer session in support of traditional marriage.

Korean Christians, therefore, were just one fragment of a much-larger crusade. Similarly, eight years ago, when Proposition 22 (the state’s original same-sex marriage ban) was on the ballot, Korean churches circulated petitions in support of the measure. The proposition passed with 61 percent of the vote, but was later overturned by the California Supreme Court.

Kim speculated that the No on 8 campaign did not aggressively pursue minority voters the way supporters of the measure did. “How much time did [the No campaign] spend reaching out explicitly to communities of color?” he asked rhetorically. “People of color are the new majority in California. How much did the No on 8 campaign work with that reality?”

In contrast, as early as August, James Pak began working for the Protect Marriage campaign by sending letters to 800 Korean faith-based leaders in Los Angeles and Orange counties. The correspondence outlined what he believed would result if the measure failed to pass: tarnished family values, confusion among children about sex and gender, and legal problems for ministers who refused to officiate same-sex marriages.

Pak’s efforts helped convince dozens of church leaders to join his campaign, triggering an impression among some churchgoers that voting for Proposition 8 was more crucial than choosing the next commander in chief. After raising $6,000 from individual Korean donors, Pak had 14 Korean-language advertisements run on television and in major daily publications, including the Los Angeles-based Korea Times, the largest Korean newspaper in the country. Korean papers also began running articles written by pastors, urging other churches to start campaigns opposing gay marriage. Rallies and prayer meetings sprouted up. At some churches, Sunday sermons included reminders to vote yes on 8 on Election Day.

Oriental Mission Church, a Los Angeles congregation that boasts 5,000 attendees, usually doesn’t address statewide ballots, “but when there is a proposition of this nature or any kind of political statement in agreement with our biblical beliefs, then the church will get involved,” says the Rev. Matthew Kim, one of OMC’s pastors.

“The bottom line is that God created men to unite with women in marriage. So we had a moral, ethical and spiritual obligation to get the word out.”

There was no official church-wide campaign, but Kim says he did make it clear to his English-speaking college ministry that he was in favor of the ban.

Young Nak Celebration Church, the English-language leg of mega-church Young Nak Presbyterian of Los Angeles, advocated for the proposition, but church officials declined KoreAm’s interview request.

[ad#336]

Backlash Swings Both Ways

There was something about the very personal issue embodied by marriage and even the very word that unleashed an emotional reaction and revealed passionate divisions within families and circles of friends.

One 29-year-old Korean American Christian who requested to be identified only as P. Kim said he and about nine close friends had a huge argument via email over the issue. Kim, who opposed the measure, pointed out to his Yes on 8 friends that there is a Bible verse calling for those who commit adultery to be killed, but most Christians don’t advocate killing those who cheat on their spouse. So he questioned, why do people use the Bible to justify keeping same-sex couples from marrying, or even from being?

“People arbitrarily pick and choose what they want to believe and follow, when it comes to the Bible,” Kim wrote his friends.

Notably, several individuals declined to have their names published for this story because of fear of backlash from the opposing side. On the one hand, No on 8 voters don’t want to be labeled as anti-Christian, while the Yes on 8 backers don’t want to be seen as bigots.

“I have gay friends,” says Erin Lee, a Christian and college student in Los Angeles. “I was torn over how to vote. I didn’t know what to do. But the reason I voted yes was because, where do we draw the line? If we allow gay marriages, then what’s next? A man and animal? A man and a child? We have to maintain some sort of conventionalism. I feel horrible. I don’t want it to seem like we’re trying to take away their rights.”

One Orange County resident who asked her name not be printed said she felt conflicted over how to vote all the way up until reaching her polling booth.

“At my church, at the pulpit it was said you must vote yes on 8. There was no question about it,” she says. Her husband agreed and voted in favor of Proposition 8, but her deliberation was not as clear.

“On the no side, was this an issue of civil rights or social affirmation?” she recalls asking herself. “On the yes side, was this a stand on faith or religious intolerance? I went back and forth with these issues.”

The 40-year-old stay-at-home mother who considers herself progressive ended up voting that day, but not on Proposition 8. In her mind, marriage is between a man and a woman, she concluded. “But the word ‘ban’ rang all the bells.”

The Korean American lamented the divide she thinks the issue has unleashed, in particular the “witch hunt” atmosphere, with businesses being boycotted if the owners are revealed to have been donors of the Yes on 8 campaign.

That backlash swings both ways.

[ad#336]

Six weeks before Election Day, the Korean Resource Center, a grassroots organization in Los Angeles, released its bilingual voter guide that urged the 35,000 registered voters on its mailing list to oppose Proposition 8 because “everyone has the right to live free of discrimination.”

The move provoked a reaction so strong that a week after the mailing, a deluge of emotionally-charged phone calls came into the office, surprising and even intimidating the staff. One KRC employee, who attends a Korean Christian church in Los Angeles, received harassing calls on her cell phone long into the night by anonymous members demanding that she leave the congregation.

“It was disgusting,” says Dae Joong Yoon, KRC’s executive director. “We got many threatening calls from many angry community members saying, ‘How dare you take on this position? There are no gays and lesbians in the Korean American community; they don’t exist. They are worse than dogs and pigs. Why are you siding with sinners?’

“We began to worry — not if Prop. 8 would pass or not — but how hate was somehow [being] generated by lies and baseless information,” adds Yoon. “Hate against other human beings, and thinking gays and lesbians are worse than animals … that’s something we need to think about. Where is that coming from? And why?”

Weeks earlier, KRC and its sister organization, the National Korean American Service & Education Consortium, also became increasingly aware of articles in Korean newspapers written by Proposition 8 supporters.

HyunJoo Lee, the organizing coordinator of NAKASEC recalls an op-ed published in the Korea Daily on Oct. 3 that used an anecdote about a college student getting gang-raped by gay men in his dorm room as a reason why readers should vote yes on 8.

To counter what they saw as increasingly-transparent homophobia in the Korean community, KRC, NAKASEC and API Equality, a Los Angeles coalition that promotes marriage rights, asked Korean faith-based leaders to speak against the measure to the public and Korean press. Among them was Dr. Julius Nam, a professor of religion at Loma Linda University, who sees same-sex marriage as a “fundamental human rights issue.”

“By limiting and eliminating the rights of same-sex couples from marrying,” he says, “Prop. 8 is creating a second-class union of individuals in society.”

His stance against the ban was also based on the principle of the separation of church and state. “It’s a particular group of Christians that is trying to legislate their particular theological understanding of marriage,” he says. “I find that troubling.”

Like the two other church leaders who spoke out against Proposition 8, Nam has since become the target of community criticism, with some Koreans questioning whether he should be a professor of religion. These types of reactions explain why supportive or even sympathetic ministers continue to “remain in the closet” about gay rights, he says.

One Korean minister in California, who spoke under the condition of anonymity because of the subject’s sensitivity, voted against Proposition 8.

“Korean gays and lesbians are alone, and it’s sad that our community doesn’t want to respect their civil rights,” says the minister. “And I am doubly sad and disappointed that I cannot be courageous enough to openly support gay marriage because of where I stand as a minister.”

[ad#336]

‘Change Is Inevitable’

Park recalls his wedding ceremony — a June 17 ritual at West Hollywood Park, during which scores of same-sex couples received marriage licenses for the first time in California history. That year, Park and Dean Larkin had been a couple for 10 years. Right after Japanese American actor George Takei, with husband Brad Altman, became the first to legally wed, Park and Larkin tied the knot — which was covered in both the mainstream and Korean media.

“There is a magical moment that makes marriage different,” says Park, 35. “A moment of truly experiencing that sense of complete equality, being part of a family and having the societal recognition that everyone deserves.

“To be able to call Dean my husband, to not have to explain what it means to have a partner or to live with him, is a freedom.”

Park is also an Episcopalian, a parishioner in good standing at St. Thomas the Apostle in Hollywood. He has been singing in church choirs for 16 years.

It was at a religious conference several years ago, in fact, when he heard someone ask South African apartheid opponent and Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu why he fought so hard in the face of adversity. “And he had a grace about it, that ultimately, these are all about human rights,” says Park, trying to hold back tears. “And if we really can learn to love one another, there are no other rights to fight for. It’s this grace that the Korean community is missing. If anything makes me sad, it’s seeing that we haven’t quite gotten there yet.”

It’s still unclear how Proposition 8 will impact the status of the 18,000 same-sex marriages like Park’s that took place in California after the state Supreme Court announced its ruling in May that people have a fundamental right to marry the person of their choice.

During the weeks following the election, multiple lawsuits were filed, challenging Proposition 8, and on Nov. 19, the California Supreme Court announced that it would review the ban’s legality. Gay and lesbian couples will not be permitted to marry until the court has ruled.

Both sides of the Proposition 8 campaign are already looking ahead to 2010, when same-sex marriage could re-visit the California ballot.

Perhaps the greatest irony of the Yes on 8 campaign is that much of what same-sex opponents fear is already happening, perhaps not formally or under the “marriage” banner, but in reality. In the United States, it is estimated there are 594,000 same-sex partner households, with many including biological children, according to the 2000 Census. Nationally, 33 percent of female same-sex households include biological children under 18, while 22 percent of male same-sex households do. Some 38,200 Asian Pacific Islanders identify themselves as living with same-sex partners.

“Change is inevitable,” says Park. “It’s just a question of how much pain and suffering we have to go through to get there.”