By Jinah Kim

Illustration by Kyungduk Kim

I was warned that it could happen, that I could be kicked out of my own father’s funeral. But I didn’t believe it would happen.

Until it did.

[ad#336]

Five years ago, I was at the memorial service for my father, who had died of Lou Gehrig’s disease on Halloween day. I sat next to my family in the front row of the Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall in Marina, Calif., staring numbly at my father’s framed picture. “Dong Soo Kim was a wonderful father, husband, Christian…,” the elder remarked. He concluded the service with prayer. I was nervous about what was supposed to come next, but was too sad to think about it seriously.

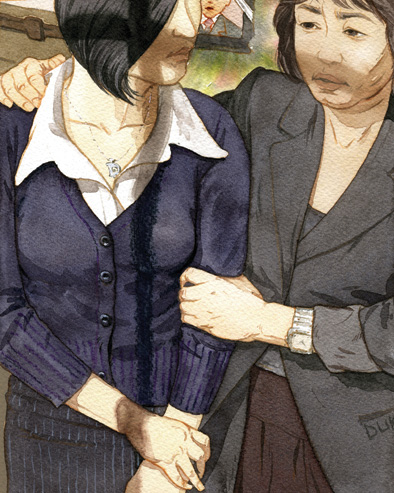

Suddenly, my aunt came up to me and grabbed my elbow to lift me out of my seat. “OK, let’s go,” she said softly. Before I could protest, she was leading me up the aisle, her hand firmly gripping my arm to make sure I couldn’t flee. As hundreds of solemn eyes looked on, I was marched out of the church like an inmate being led away to jail.

Once outside, I flung my arm out of my aunt’s grip and screamed at the top of my lungs.

***

[ad#336]

I was raised Jehovah’s Witness. As a child, my mother would come to my room at the end of each day to kiss me goodnight. To lull me to sleep, she would stroke my hair and tell me how much she, my dad and God loved me. Then, just as I was drifting into slumber, she would abruptly add, “Jinah, remember, the devil walks about like a roaring lion, ready to devour people. If you don’t stay faithful to God, you become easy prey. Good night.”

As the rest of the house slept, I would lay there buried and sweating under my covers, picturing Satan lurking around my room, eyeing me hungrily. At my tender young age, I concluded that the only reason I was still alive in the morning was because I was a faithful Jehovah’s Witness.

And that I was. I embraced my faith with a fervor and zeal that was rivaled by few other Jehovah’s Witnesses my age. I gave public talks and participated actively in our tri-weekly meetings. I would go knocking door to door in my neighborhood, trying to convince everyone and anyone who would listen that Armageddon was coming soon, and that unless they too became Jehovah’s Witnesses, they were doomed to eternal death. I was the darling of my congregation, and I prepared myself for a future as a missionary. My parents were bursting with pride.

[ad#336]

Then, during my junior year of high school, my parents lost their grocery store, which was our livelihood since immigrating to the U.S. Suddenly, we found ourselves near poverty, and I saw my parents struggling to find odd jobs to keep us fed and clothed. Frightened, I decided I never wanted to be in that same situation when I got older. I put my plans of becoming a missionary on hold, bought myself an SAT prep book and applied to college. I was accepted into UCLA.

Back then, Jehovah’s Witnesses opposed higher education, believing that it was a four-year investment in a world that was about to come to an end. My parents and the entire congregation tried to convince me not to go. But I remained firmly resolved, and for the first time in my life, left the comforts of home.

In college, I tried to stay active as a Jehovah’s Witness. But something was clearly changing my mind: It was losing its narrow, closed-mindedness as I absorbed fascinating information about the world around me. I was experiencing life as I never had before. By the time I graduated, I had all but left the religion, no longer able to tolerate its intolerant ways.

Two years after graduation, I was “disfellowshipped,” which essentially means I was excommunicated by the religion. Elders at my congregation discovered I had a male roommate. I didn’t know this was a reason for disfellowshipping; I found a place I liked and needed a roommate badly, and the only one who responded to the ad was a guy. But despite my protests and appeals, the elders publicly announced my fate at the next meeting, and the deed was done.

[ad#336]

When you are disfellowshipped, no Jehovah’s Witness is allowed to speak to you. Even your own family members are encouraged to cut off communication. And so on the day of my father’s funeral, I could not stay in Kingdom Hall to mingle, accept condolences or represent my family. My mother was so afraid I would interact with Jehovah’s Witnesses that she had my aunt escort me out as soon as the prayer was over. That same year, I was kicked out of my grandmother’s funeral in much the same way.

Eventually, for the sake of making peace between my mother and myself, and because I could not bear the thought of not being able to attend my mother’s funeral when she dies, I decided to get the ban lifted. After six months of Jehovah’s Witness meetings and swearing that I’ve repented of all of my sins, I was “reinstated” into the congregation. With the big “D” figuratively un-stitched from my chest and having exchanged my shameful title for a clean one, I won my mother’s relief, and the ability to communicate with Witnesses again.

Still, in my heart, I had left the church long ago.

I don’t regret having grown up Jehovah’s Witness. I think I am stronger today because of it. And because my mother cannot live without the hope the religion provides, nor without the tight-knit community of like-minded people who encourage her emotionally and spiritually, I support her wholeheartedly in her way of life.

But for me, that chapter of my life is done. And for now, I think I’ll keep it that way.

Jinah Kim is a reporter for NBC News and KNBC in Los Angeles.