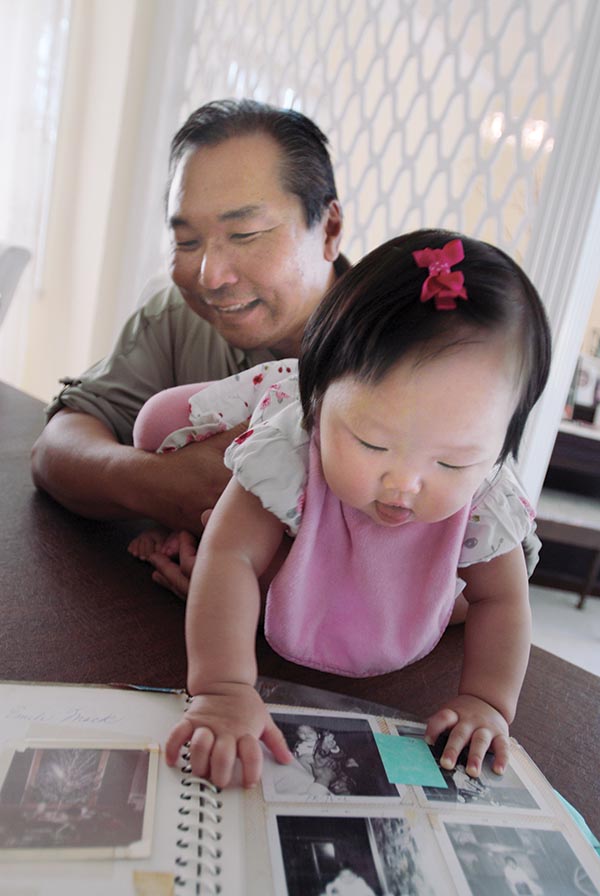

Emile Mack, at age 6 or 7, with his father Clarence Mack, in Los Angeles.

Emile Mack, at age 6 or 7, with his father Clarence Mack, in Los Angeles.

Emile Mack may be the highest-ranking Asian American firefighter of a major American city, but what tends to surprise people most about the Los Angeles Deputy Fire Chief is his most unique background: At age 3, he was adopted by an African American couple. His is a story that challenges our notions of race and identity; it’s about the ties that bind and the gift of family.

By Elizabeth Eun

Photos courtesy of Emile Mack/By Eric Sueyoshi.

• • •

From Emile Mack’s corner office on the top floor of Los Angeles City Hall, one can see the vast downtown skyline. It seems an appropriate view for the second-in-command of the city’s 3,500-person fire department—perhaps a reminder of the daunting responsibility of protecting this sprawling metropolis. As deputy chief of operations, Mack in fact is the highest-ranking Asian American firefighter of a major American city.

That’s an especially impressive fact, given the reputation of fire departments as traditional bastions of white males. After implementation of a 1974 consent decree, the Los Angeles Fire Department has certainly come a long way in diversifying its force, with roughly 49 percent now comprised of racial minorities (Asians are 6 percent of that figure), according to the department. Still, the image of Mack’s Asian face standing shoulder to shoulder with high-ranking local and state officials at the scenes of major Southland fires is quite stunning.

But Mack, 53, is quite used to standing out—and not just because he’s been a firefighter for 32 years. Rather, the high cheek bones and almond-shaped eyes may signal a Korean background, but his identity, his culture and the place he called home throughout his childhood were intimately tied to the parents who raised him. That is to say, he long identified with the African American culture, and shades of brown were the faces with whom he felt the closest.

After being abandoned at a South Korean police station as a baby, he was adopted in 1960 by Undine and Clarence Mack, an African American couple. That statement alone is enough to floor people unfamiliar with his backstory. Yet, as Emile tells it, it’s really a simple tale: The Children’s Christian Society brought photographs of children from a South Korean orphanage to his parents’ Los Angeles church. And Undine and Clarence decided to make the 3-year-old boy with the big button cheeks their son.

And all the queries that naturally arise upon learning that his parents are black—Did you struggle with your identity? Did you ever feel like you didn’t belong? Do you consider yourself black or Asian?—are quietly shut down with answers that make the questioner feel slightly foolish for the asking.

“I grew up not trying to identify, but naturally identifying with the people around me, the African American culture,” says Mack. “From before I can remember, I was surrounded by African American people. They were the ones I saw every day, they were my family, the people I lived with, who loved me, took care of me and played with me.”

Certainly, he acknowledges most people are surprised when they find out he was raised by African American parents. When one talks about transnational adoption or even cross-racial adoption, it usually involves white parents and ethnic adoptees. In essence, Mack’s story can be interpreted as an testament to the strengths and beauty of adoption, period. It’s a story that is coming full-circle, now that Mack and his wife Jenny have recently adopted a baby girl, Miya, from South Korea.

“My family always made me feel part of the family, and I never experienced from any of them, ‘Oh, you’re different.’ They loved me and took very good care of me,” says Mack. “I knew where I came from.”

And that’s the same kind of love and grounding he plans to pass on to his daughter. It’s a gift, a legacy, from his parents that has served this Korean adoptee well for five decades—all the way to the top of an agency appropriately charged with serving residents of one of the nation’s most ethnically diverse cities.

• • •

AN INDIVIDUAL IDENTITY

Mack playing with family friends.

There wasn’t necessarily an adoption talk with his parents per se that Mack can point to, but he does recall a moment around age 4 or 5 when he started recognizing he didn’t look like Mom and Dad. “[I remember] looking at myself and my parents, and thinking, ‘This must be what ‘adopted’ means,’” says Mack. “It was like… now I see it, and now I can comprehend what it means.’ ”

Still, Mack, who grew up in the Crenshaw district of Los Angeles, doesn’t recall ever struggling with his racial identity as a child, even when outsiders teased him.

“There were people who didn’t know me or my family, and they didn’t tease me because I had black parents, but they teased me because I looked Asian. So it was the typical thing, ‘Hey Chinese, hey this, hey that.’ And then my friends would respond, ‘He’s black!! His parents are black, leave him alone!!’” said Mack, his face lighting up at the memory.

“In fact, that still happens today. There are times when I walk into a room with black friends, and they’ll walk up to someone I don’t know, and say, ‘Hey man, he’s cool. He’s a brother.’ And they’ll immediately accept me just because my friend says, ‘Oh, he’s one of us.’”

Friends from Mack’s childhood affectionately remember him as the “little Asian kid who ran with the black kids.”

“Way back at that young age, you didn’t differentiate between Chinese, Japanese, Korean, you just knew they were of Orient descent,” says longtime friend Dwayne Golden, who attended the same elementary and junior high schools as Mack. “It was just black versus white, and everyone else just fell in the middle. But I remember [Mack] was different, because all the Japanese friends I had at the time, they were very disciplined and studied a lot, but he was always hanging out with the other black kids.”

Still, Mack’s upbringing perhaps challenges people’s expectations of what growing up in a black home means. Sure, Mack recalls a home filled with his “parents’ music,” which included Aretha Franklin and Nat King Cole, and while other ethnic Korean children may have had bap and kimchi for dinner, he was eating “what some people call soul food.” However, he also points out, like many parents across color lines, his emphasized studying hard and doing his best. He also notes that because his father had worked as a chef, the family enjoyed a more international offering at the dinner table, with Chinese, Mexican and Italian cuisine on any given night.

Mack with his mother Undine at an Asian Pacific Islander American Heritage Month event.

His parents were also international in their lifestyle. Their wide circle of friends included people of every nationality.

“My father was a strong believer in the rights of everyone,” says Loretta Cooper, Mack’s half-sister, speaking of their late father who died in 1983. (Clarence and Undine Mack’s union was the second marriage for both.) “It wasn’t just a black-white issue, so you have this environment of people who believe that everyone should have the same rights and equal access. And that speaks to the fact that [my father and Undine] were able to adopt and raise a child who wasn’t in their own ethnic group. It shares what their belief system is about and that love doesn’t have anything to do with what a person looks like.”

Mack may have “run with the black kids,” but he also had playtime and dinners with his Caucasian, Hispanic and Asian friends. The latter gave him some early exposure to Asian culture, though his first taste of a certain perennial Korean dish would come from an unusual source.

While visiting a desert vacation home in 29 Palms, the Mack family would often stop by a small store owned by a Caucasian woman and her Hawaiian husband. The store catered to the Asian wives who lived on the nearby Marine Corps base, and stocked all kinds of Asian food.

“When the Caucasian store owner found out I was Korean, she went back into the cold storage, brought out this little bottle, and said, ‘This is kimchi! This is one of the things Koreans like to eat!’” recalls Mack, who was 12 or 13 at the time. “So I ate it, and I remember that I immediately liked it. So my first exposure to kimchi was in the middle of the desert, at this little store owned by a Caucasian woman.”

It wasn’t until Mack entered high school that he started hanging out with more Asians and exploring his Asian identity, but this wasn’t to the exclusion of his black identity. In fact, he cites high school as a period when he was “talking black” and “acting black,” ironically as a way to fit in with the Asians at his school who were “trying to be cool.”

“I can’t really assign my personal traits and characteristics to being Asian or black,” says Mack. “We can be stereotypical—Asians work hard. Well, my black parents worked hard. Asians are quiet. Well, I can be quiet, but I don’t know if I’m quiet because of [my] Asian [background]. ”

What Mack does know for sure is this: “The person you are is the person you are within, and to look different from your parents, you have to have a certain level of strength to deal with people who look at you and say, ‘Why are you different from your parents?’ But it truly is about who you are inside, and not about whether you look like [your parents] or if you don’t look like [your parents].”

Indeed, while talking to Mack, what is almost immediately apparent is the sense that he isn’t trying to be something he’s not.

“Emile was always an individual,” says Golden, who also works for the fire department with Mack. “There are some people, who, whether you’re black and work in a Korean environment, or if you’re Korean and work in a black environment, you just take on that culture and try to sound like the people you’re around. But Emile, even though he had a lot of black affiliation, he was just himself. He wasn’t trying to fit in with one group or the other; he didn’t act black, or act Korean. He was just acting like Emile.”

And to be Emile Mack today means embracing both the African and Asian cultures that are part of him. He has long been involved with various black organizations, but he admits he is currently more active with Korean American organizations, recognizing the influence his Korean American friends have had in his life. He is a frequent guest speaker at Asian American events in Los Angeles, and enjoys talking about his role in the fire department especially to Korean American youth.

“He’s very proud of his Korean heritage,” says friend Alexander Kim, who formerly worked for ex-California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. “[That] really means a lot and gives courage to other Korean adoptees.”

• • •

FIGHTING FIRES

Mack, with former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and other local officials at the scene of a 2008 brush fire in Sylmar.

Mack may hold the distinction of being the highest-ranking Asian firefighter in a major American city, but he says his foray into firefighting happened on a whim—one that wasn’t even his own.

“My best friend from high school came to me one day, and he said, ‘Come take the firefighter’s exam with me!’” says Mack, who was in his junior year at the University of California, Los Angeles, at the time. Mack and his friend both passed the written exam, and after training for the physical abilities test, passed that as well. “So it gets to the point where I’m pretty invested in the process, and after we pass the interview and the medical and background check, we were offered jobs.”

Mack, who had been a pre-psychology major and had planned on going into optometry, dropped out of UCLA and joined the fire department, to the elation of his father and the concern of his mother, who worried for his safety.

Giving her more cause for concern, no doubt, were the events unleashed on April 29, 1992, when the city of angels exploded into fires and violence in what scholars would later deem the nation’s first multiethnic riots. As a firefighter then based at a South Los Angeles station, Mack was literally at the center of the chaos.

“We were just going from fire to fire, and it was just devastating to see everything that was happening. Things just started not making sense,” says Mack. “We were at the first fire, which started on Vermont and 8th [streets], and as we’re getting out of the truck and starting to hook our hose up to the hydrant, two carloads of people pull up to the store and begin shooting into the stores. We ducked behind this little stone wall, and then the Korean shop owners came out of their stores and start shooting back.

“Then we’re crawling to get back to the fire truck so we can move out of the area, but after about five minutes had passed, we looked around and we could see the next block and the next block going up in flames. And within the next few hours, there were fires as far as you could see down Vermont.”

Mack recalls running into his firefighter friends throughout those three days, all of whom were constantly calling their wives and girlfriends to let them know that they were alive. His then-fiancé-now-wife Jenny was also anxiously waiting, not only to see if Mack was safe, but also if they were going to be able to get married on their planned wedding date that weekend.

“We thought and thought, and that morning, we just said, ‘Let’s do it.’” says Mack. The two married in Malaga Cove in Palos Verdes Estates, with a reception in Redondo Beach at the Blue Water, which meant the guests, half of whom were firefighters, had to go through roadblocks to get there. All 120 guests made it.

“We had a young Caucasian DJ, and as the couples were dancing, he was crying, and he said to us, ‘This is so beautiful; that there are Asians and blacks and whites and Hispanics, and every race is here enjoying themselves together after such a horrific time during the riots.’” recalls Mack. “It wasn’t until this young DJ said this that it really struck my wife and me how really marvelous this is, and that our lives are so rich with friends of so many different cultures and backgrounds, able to celebrate together.”

Young firefighter Mack boards his engine in 1980.

A few years after the riots, Mack attended a conference with religious leaders from both the Korean and the African American communities—two groups pitted against each in the period prior to, as well as during, the 1992 crisis. The mainstream media was accused of fanning the flames with the frequent “black-Korean conflict” headline, after a Korean immigrant merchant shot and killed an African American teenager after a scuffle in a South Los Angeles store in 1991.

When asked to comment about the riots at the conference, Mack said, “It hurt me very deeply that the two cultures that are me were in conflict and were at odds.”

But he also saw hope in the efforts by leaders from both communities trying to understand each other. “That took me through the pain of seeing my two heritages at odds, seeing the hope and future that they could build an understanding, and build better relations with each other.”

And given his unique identity and prominent position, Mack recognizes his own role in bridge-building.

“Because I do come from a very diverse background, I’m very comfortable in any form or setting, with any group of people I have to work or interact with in my job,” says Mack.“That definitely has made me more capable and makes me more understanding of differences of cultures.”

It’s a leadership role not just restricted to cross-cultural issues. Although Mack likes to paint his rise through the fire department ranks as merely a series of promotional exams that led to more promotions, his friends and colleagues acknowledge what Mack humbly won’t.

“He looks like a big teddy bear, but the man commands a very strong presence, and he’s a very strong leader and commander,” says Derek Tran, a Los Angeles consultant who met Mack in 2004 while Tran was working for then-Mayor Jim Hahn. He considers Mack a father figure and mentor. “You just sense leadership when you’re around him, and it obviously shows, because he’s No. 2 in the fire department now. You don’t get there by being wimpy.”

Tran says Mack, who was promoted to his current position in April of 2007, brings to the table a unique vantage point. “I think he identifies with the African American race, the Asian race, the American race,” says Tran.

Perhaps, quite appropriately, Mack, while working in the fire department’s Bureau of Training and Risk Management in 2007, helped revamp the recruiting process, in an attempt to further grow a force that reflects the city’s multiethnic makeup. White males have historically tended to dominate the applicant pool. The recruiting initiative paired prospective candidates with firefighters who advise the former through each step of the application process.

“We have to show women and people of color that we want you, and we’re willing to do everything possible to show and help you through the process to show you that we want you on LAFD,” Mack told the Los Angeles Daily News in 2007.

The mentorship, now institutionalized, also occurs with non-minority candidates, and all recruits are taught, among other things, how to work in an environment with zero tolerance for discrimination and harassment.

• • •

‘WHAT MY PARENTS HAD DONE FOR ME’

Mack with wife Jenny and daughter Miya at their Redondo Beach home.

A grand “Certificate of Appreciation” from the city of Los Angeles figures prominently in the center of Mack’s office wall, but it is notably covered with photos of his baby daughter, Miya, and Jenny, his wife of nearly 20 years. And while his stack of books includes titles like On Mission & Leadership, the book that tops it is a book of Korean recipes, translated into English.

For Mack, now more than ever, learning more about Korean culture is a priority, since it is the country that his adopted daughter has so recently come from—and is the country from which he himself came 50 years ago.

Mack has attempted to uncover more details about his own roots. But despite the help of Korean friends and his original adoption papers, he’s learned very little. The orphanage he was adopted from no longer exists, and the Children’s Christian Society that arranged his adoption has since been taken over by the Social Welfare Society, which does not have any records on Mack.

But at this point in his life, Mack seems, if not fine with the situation, resigned to it. And while the Social Welfare Society doesn’t have his own adoption records, it does have his daughter’s.

“When I was younger, I always said, ‘I’m going to adopt,’” says Mack. “As I got older, I started understanding what my life could have been like had I not been adopted, and appreciating what my parents gave me; it went from wanting to adopt just because I had been adopted, to wanting to do what my parents had done for me for a child in Korea.”

Mack, who has a 24-year-old son from a previous relationship, and Jenny began the lengthy adoption process over three years ago, which was made more arduous since both were over 45, the age limit set for international couples seeking to adopt from South Korea. After receiving help from fellow Korean adoptee Steve Morrison of the nonprofit Mission to Promote Adoption in Korea, the couple was granted special permission from the South Korean government. With their case, the Macks, in fact, helped eliminate the age limit policy.

In October of last year, Emile and Jenny flew to Seoul to meet their daughter. “When we arrived at the home, Miya and her foster mother were out front, and I saw Miya from the car and she smiled at me, and I said to Emile, ‘I think she recognizes us!’” says Jenny, who later learned that the foster mother had been showing Miya photos of the couple.

“That was one of the first big reliefs,” said Emile, “that there was already some beginning of a connection.”

Miya Miyoung Mack, who already seems situated in the Macks’ bright family home (she has an entire corner of the living room dedicated to her, complete with plush pink pillows and stuffed animals), turned 1 in January, and the Macks have already begun the process of ensuring that she is able to experience her heritage in a tangible way. With the help of Korean friends and a party planner, Emile and Jenny, who is Japanese American, last month planned a traditional Korean dol party for her first birthday.

“We want Miya to be connected to her culture so she understands our shared Korean culture,” says Emile, speaking of the bond between father and daughter. “One of my friends is helping me learn to make Korean food, and I just ordered Rosetta Stone for Korean, so she and I will be learning together, you know, the gamsahamnida and the annyeonghaseyo. Hopefully, I’m just a little more advanced!”

It’s unmistakable that Mack wants his daughter to know where she came from, but he also doesn’t want her to forget where he came from. He wants Miya to know that, despite what outsiders may think, he isn’t different from his parents— at least not where it counts. “I don’t have prejudice because [my parents] didn’t have prejudice,” says Mack. “Because they lived that way, I lived that way, accepting every type of person. I learned from the way they lived.”

• • •

[ad#bottomad]