By Helin Jung

A handwritten paper sign directs visitors to “Jim Kim’s office” at the Harvard School of Public Health. Once there, the space is noticeably still, almost silent. Bookshelves are filled to a fraction of their capacity, with an empty conference table in the corner.

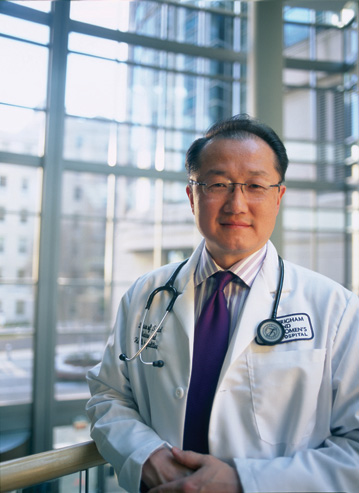

When one imagines the work space of a person actively trying to save the world, or at least, do his part, somehow, this scene at the Boston offices of the Francois-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights doesn’t meet expectations. And yet, from this cavernous space, Dr. Jim Yong Kim is doing just that. This physician is engaged in the seemingly impossible fight to equalize health care access and treatment for people all over the world.

Currently the chair of the Department of Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School in Cambridge, Mass., and the chief of the Division of Social Medicine and Health Inequalities at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Kim has devoted his life to this pursuit of social justice in health care. And his work toward that end has been recognized. In 2003, Kim was awarded a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, also known as the “genius grant.” He was appointed the director of the HIV/AIDS Department of the World Health Organization in 2004. Last year, he was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world, and is consistently cited as one of the leading contributors to global health policy.

In the world-saving circles, he is perhaps best known for his work with Paul Farmer, a similarly trained physician and anthropologist who in 1987 founded Partners in Health (PIH). Kim joined the Cambridge-based nonprofit while a Harvard Medical School student and is credited now in PIH historical literature as a co-founder of the organization, which describes its admirably ambitious mission this way: “At its root, our mission is both medical and moral. It is based on solidarity, rather than charity alone. When a person in Peru, or Siberia, or rural Haiti falls ill, PIH uses all of the means at our disposal to make them well — from pressuring drug manufacturers, to lobbying policy makers, to providing medical care and social services. Whatever it takes. Just as we would do if a member of our own family — or we ourselves — were ill.”

Armed with this vision, Kim has traveled with Farmer from Haiti to Peru, Russia to Rwanda, to treat the health problems of the poor. They have gone into neighborhoods suffering from near-epidemic cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis, and have used guerilla-like tactics to bring treatment to their patients. For some perspective on the dangers of being in this kind of environment, one need only look back at the recent case of the newlywed placed on lockdown after traveling across the United States with this form of TB, commonly known as MDR-TB.

In 1999, the World Health Organization appointed Kim and Farmer to help lead the international response to drug-resistant TB by establishing pilot treatment programs and organizing delivery systems for antibiotics.

Although Kim and Farmer were initially viewed by the international health community as dreamers who did not understand what they were up against, a decade and a $45-million Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant later, drug-resistant tuberculosis is being treated successfully in 50 countries, and PIH has served as a leader in that fight.

Throughout much of his career, Kim has played the understudy to Farmer’s iconic figure, about whom a Pulitzer Prize-winning book has been written, but that’s just fine with him.

“It’s kind of the difference between Paul and me. Paul is from the Catholic tradition, where you’ve got to get things going quickly because you’ll probably be dead by the age of 33. The Messiah complex people have got to get it done early,” Kim described, laughing. “We need Paul so much because he’s a model for how we should live in the world. But, if the requirement was that everyone lives like Paul Farmer, then the poor are just screwed.

“The key is to have everyone able to contribute in some way to making the world a better place, and if we don’t do that, if it’s still this extraordinary act of will and self-negation, then we’ll never get there.

“I live in a nice apartment in downtown Boston, I come in [to work] at 9, I go home at 6, and I’m trying to make it possible for everyone to be able to do social justice work, and have a family, and lead a normal life, and maybe even play golf once in a while. Because that’s when we’re going to win.”

***

Born in Korea in 1959, Kim moved to Dallas in 1964, when he was 5. Later, they moved to Muscatine, Iowa, where his father set up his dentistry practice. Known as the best dentist in town, Kim’s father also worked as a professor at the University of Iowa. His mother, a philosopher who had studied at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, was also at the University of Iowa working on her doctoral dissertation.

It was his mother who instilled in Kim the values of social justice and being politically active. She made it clear that it was important for Kim to respect every human being. When he was 12 years old, Kim campaigned for George McGovern, the 1972 Democratic presidential candidate. While in high school, he joined Model United Nations, and spent a week in New York at the real U.N.. While it was common for him to endure racial epithets, Kim still managed to play the roles of quarterback of the Muscatine High School football team, valedictorian and president of his class.

“Real racism, in my view, is where you can’t eat, you can’t get a job, and it’s hard for you to survive because of your race,” Kim said. “We never experienced that. … My father had a good job, and my mother could do her Ph.D., so we were fine.

“[Our] identity as Koreans was far less important to us at the time than our identity as people who were engaged in the world in a very different way than almost anyone else in Iowa, and that’s really what I felt more than anything else.”

Kim left Muscatine for the University of Iowa, then transferred to Brown University, where he came to explore his Korean identity.

“I was really involved in what we were calling the Asian Movement, so it was an awakening for me,” said Kim. “It really wasn’t cool that, here I was, a Korean American, and I couldn’t speak Korean.”

He went from Rhode Island to Massachusetts to start his studies as a dual-degree master’s and doctoral candidate at Harvard University, opting to do his dissertation in anthropology. He was able to work through more of his “identity crisis” by doing his research in South Korea.

“The important thing was, what does it mean to me to be Korean? So, most people resolve their identity crisis by going back for a few summers and having a girlfriend or a boyfriend. But me? I’m always the extreme. I had to do a Ph.D. in anthropology to resolve my identity crisis.”

He completed his 350-page thesis, “dealt” with his cultural identity crisis, learned to speak fluently, then decided he couldn’t find his life’s work in Korea, and kept returning to the idea of social justice. That’s when he met Paul Farmer.

Farmer told him that what Kim had struggled with all this time had nothing to do with race, and everything to do with class. “[What you care about] is really a poor people’s issue.” That’s when Kim joined Farmer at PIH, and the rest is history.

Kim was able to take his philosophies and experiences with PIH to work in Geneva, Switzerland, first, as the senior adviser to the director-general of WHO, Lee Jong-Wook, then as the HIV/AIDS director. Dr. Lee was a tremendous influence in Kim’s life, inviting him to sit in on private meetings with nearly all of the world’s ministers of health, and allowing him to take extraordinary risks as the HIV/AIDS director. Lee’s influence extended into Kim’s parenting style, virtually giving him the permission to take the time to focus on his family.

Kim’s wife, Younsook Lim, a pediatrician, is currently taking a course at the Harvard School of Public Health. During this time, Kim does not travel, and instead, has the chauffeuring duties of dropping off his 7-year-old son at summer camp every morning at 8, and picking him up every afternoon at 3:30.

“Now, what that means, of course, is that I’m up at 5:30 doing e-mail, and I’m still up at 10 at night doing more e-mails and work. But, one thing I learned from Dr. Lee is that [it’s OK to spoil your kids].”

Kim points out that though he and Lee had a special relationship, Lee was always hard on him, and “tried to make it clear that he was not being nationalistic and nepotistic. He never gave me any special treatment.”

Together, they launched the “3×5” initiative, which projected a target of 3 million people getting treatment for AIDS by 2005. It was, on the surface, too ambitious a goal, with critics echoing the “crazy” name-calling of the past, and the organization fell short of the target by 2 million. On the upside, 1 million people did get treatment. The campaign’s real legacy is that last summer, the G8 countries adopted a resolution that committed to universal access to HIV treatment by 2010.

Kim was clearly ready to relieve himself of his duties in WHO, a large, bureaucratic institution that, with 192 member states is, “the ultimate affirmative action program,” as Kim puts it. Things happened at a pace much slower than that of an academic institution or a nonprofit such as PIH.

And, Kim wanted to get back to the States.

His stint as the HIV/AIDS program director ended in 2006, and now Kim is settling back into a life in academia, with three jobs, no less.

“I’m just thrilled to be back here. When people say, ‘God, three jobs,’ I say, ‘You know, it’s a typical immigrant story. We’re not comfortable unless we have two jobs; three’s even better.’”

He will be busy working, not least as a professor at the Harvard Medical School. Kim said that his students often come to him when they are about to start on rounds and ask for advice.

He tells them, “Always remember that no matter how overworked you think you are as a medical student, remember that patients are suffering most. Interns are probably suffering second most, residents and nurses are probably in third place, and you’re way down the line, OK? Just remember that, and remember that your job is to relieve suffering.”

For Kim, the socially and morally responsible life is the only life. It’s a lesson he learned while PIH was launching its health care initiatives in Peru.

Farmer, who had worked for many years almost exclusively in Haiti, had to tell his community that he would be spending less time in Haiti in order to start the project in Peru. He explained that the Peruvian MDR-TB patients were the modern lepers and were not being treated. Though Peru is far wealthier than Haiti, the question of worth never came up. Instead, the Haitian people Farmer had been working with encouraged Farmer to go to Peru, telling him that they wanted to help.

“I’ll never forget that lesson,” said Kim, who currently sits on PIH’s board of directors. “And I’m not trying to say something silly, like the poor are more noble than we, but the fact that a group of people was capable of that level of compassion and solidarity — I think that will always be an example for me.”