Though the meaning expressed by my tenuous command of the English idiom may be closer than appears in rearview, it does not change the fact that I am nonetheless a fool for finding myself here, where I swore I’d never again be. And yet, I still persist in railing about the obscenities of our American democracy that are laid bare by race.

It is a timeworn story rewritten anew by a novel coronavirus that grew into a pandemic. With its unassuming roots in animal-to-human transmission traced to Wuhan, China, the virus joined forces with human pathogens, namely ignorance and racism, and the attacks soon followed.

Even before the United States’ first inkling of the magnitude of the virus’ nuking exposure, reports from home and abroad began to circulate: Asian people are under attack.

Starting as early as last December, the reports began streaming in through social media, often accompanied by video of people being called out, accosted, spat on, dragged, beaten, sprayed with disinfectant, doused in acid, mortally wounded in deadly violence.

Increasingly, through the Trump administration’s anti-China trade rhetoric and the unwashed reaction to the political grandstanding, we found ourselves being held out to blame, then forced back to work at a slaughterhouse. For purportedly concealing coronavirus behind masked faces, for robbing the country of the freedom to leave our homes, for offshoring American jobs by the millions, and for being a perennial foreign reminder that America is no longer great, nor is it white. Again.

WE WOULD BE NOTHING IF NOT FOR THOSE WHO CAME BEFORE US

Despite the loss of life and morality brought by the pandemic, there is hope for a better life on the downside of the curve. The light in all this may come in the form of opportunity rising from the ashes of time, like an AI Gidra emerging from technology’s antibody response to adversity.

Author AJ Dungo, in an ‘Ask me anything’ Instagram story, responds to: If you weren’t an illustrator, what would you be? “That’s a great question. I never really think about that because I love what I do. But I have a bunch of other interests that would be interesting to explore: music, skating, film. Both of my parents are nurses, and it is a difficult, thankless, grueling job. They’re my heroes, and if I had the stomach for it, maybe I would fulfill the ultimate Filipino prophecy and save some lives as a nurse.”

As Dungo brilliantly observes, inspiration comes “In Waves,” and when it does, I’m reminded by my calcifying sensibilities, left to drift awash in the viral wisdom and youthful exuberance served by meme-condensed bytes of social media, that meaning in life can be found in even the most unlikely of places.

Equality, representation and justice are qualities I see everyday, rising to the surface in my newsfeed. Yes, I know. I said it. All told, these values push to the top again and again, as they represent the will of the vast majority of us. This fact is not lost on the current sitting president and his voting retinue. Oh, and you can smell the fear.

In February, Administration 45’s federal budget approved cuts to public health care subsidies, as well as funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, just as the pandemic’s engine was revving across America. Subsidies were funneled into propping up the fossil fuel and oil industries, along with a relaxation of emission standards for automakers, effectively turning back the clock on protections meant to reduce air pollution concerns in the L.A. basin and around the world, a peculiarly nascent pathology in the midst of a respiratory disease outbreak and global warming crisis.

The founding of the Environmental Protection Agency and the original Earth Day observance on April 22 both took place 50 years ago. Just like the ’60s era, pre-EPA emissions standards I grew up breathing in the absence of, these days there is a high-particulate matter-of-fact data smog stretching across our shared mental horizon, and it’s clouding the search for meaning in all that the pandemic has wrought.

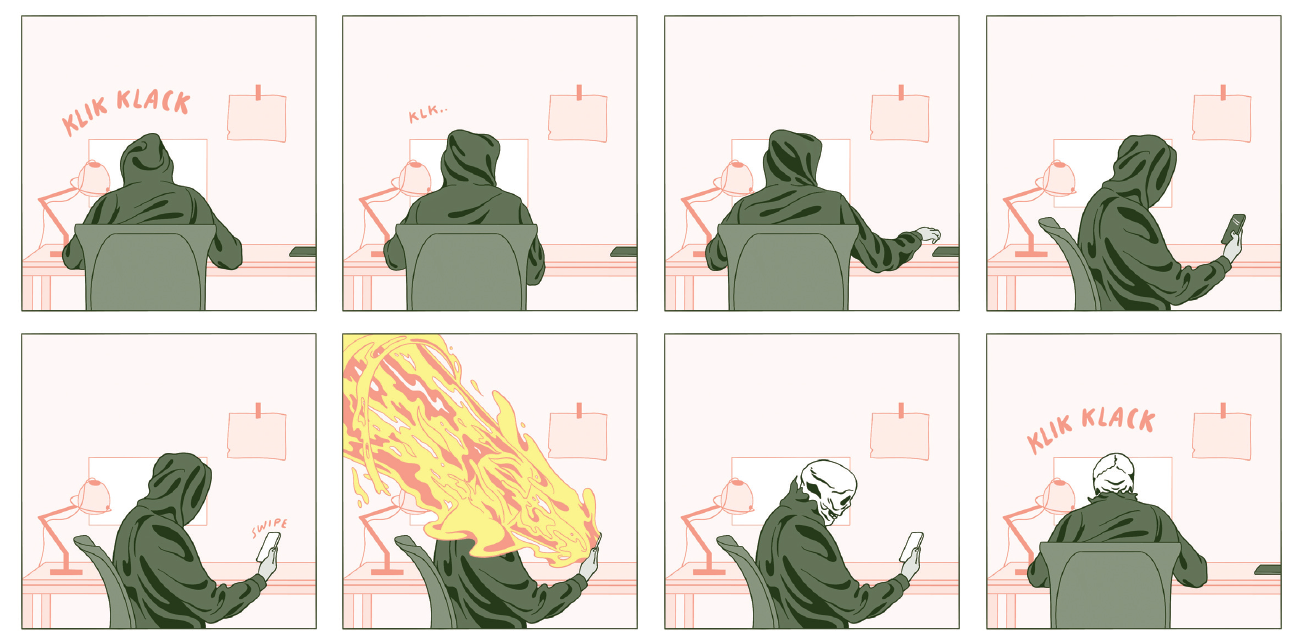

It probably does not help that my shelter-in-place research consists of low-income broadband signal and a surplus of isolation time spent scouring social media platforms with a phone screen, stealing the occasional, unsubscribed glimpse behind news media paywalls, and attending virtual lecture/story podcasts.

As these safer-at-home days dictate, I should consider myself lucky to have a cell phone and wi-fi to keep me company, as it’s all the lifeline I’ve got. So be it. I’m on a fool’s errand to mine the sh*t out of comments made across the platforms I frequent. And I’ve found, clearly, that it’s right there: the aspiration of people of all colors and walks of life to create a more caring world with common decency and respect, and where there is a semblance of justice and order. But as has always seemed to be true, it is the people, not the government, who are leading.

So now, with formalities out of the way, please join me on a responsible, socially distant crawl down the Internet’s blue highways to reach a route yonder that still holds the promise of limitless potential, in spite of the many half-steps toward equality we may trip on along the way. Indeed, it could be here, gazing inwardly in isolation before an irradiating screen, where our nation might just muster the resilience to move forward.

In tribute to my immigrant parents, upon whose shoulders I aspire to see a better future, here’s to the hope we make that journey toward progress. Together.

“So our challenge is to constantly learn from the past, and also not be bound by the past.” – Grace Lee Boggs, labor, civil rights and Black Power movement activist, 1915-2015

“Today, infectious diseases are the number one cause of death worldwide,” says Frank Snowden, professor of epidemiology at Yale University, launching into a 26-part lecture series in 2010 as if it were yesterday. “Epidemics have had an impact on history that I would regard as equal to revolutions, wars and economic crises. They are part of the big picture of historical change and not some exotic special interest.”

Snowden notes that pandemics across history have presented a scourge on the less privileged, and we see this to be the case in 2020, even as marginalized swaths of America and developing countries are introduced to the coronavirus as “a high-class import,” carried by travelers returning from business in China, studies and vacations in Europe and ski trips to the Rockies, the “Los Angeles Times” reports.

“How do people respond? Out of the relations between human beings and the moral priorities put into place by statesmen [governments] and religion,” Snowden draws a breath and replies, “we see stigmatization, witch-hunting and scapegoating.”

To this final point, what the professor observes across history and time, we are witnessing today at the speed of social media. It is an experience that comes with its own unique perils and political agency. In this time of isolation, given the opportunity for extended self-reflection, and amid a preponderance of senseless race-based hate crime, there is both moral indignation and flat out predatory aggression driving people to action.

Particularly cognizant of 2020’s election year consequences, we seem at any moment to be at a tipping point. With the longheld promise of information technology at our disposal, it could be said we are now presented, for better or worse, with a perfect storm for social change.

ORDER OF BUSINESS: JUSTICE, WHEN DO WE WANT IT?

Since mid-February, NextShark media began fielding a record number of reported hate crimes. Collaborating with marketing agency Admerasia, Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, Chinese for Affirmative Action and a matrix of community, social service and political organizations, the groups conducted a campaign to collect data and document hate crimes across the country. In less than a month, 1,497 reports from across the nation were submitted. From that data, they found that 44 percent of alleged crimes took place at private businesses, 69 percent targeted women and 9 percent were seniors ages 60 and older. The crimes included instances of health workers being targeted during their commute, at times even at their place of work while on duty.

The findings would become the basis for crime reporting to police, in some cases leading to arrests and pending prosecution, as well as providing the foundation for a congressional appeal to the U.S. Department of Justice to address the proliferation of hate crimes. The viral urgency is not lost on those who hope for a more representative government. More than two months into the accelerating spiral of violence, a group of 16 U.S. senators, all Democrats, co-signed a letter on May 1 to the DOJ that identifies more than 20 million Americans of Asian descent, two million of whom are workers on the front lines of the pandemic, in health care, law enforcement, as first responders and other essential service providers.

“We write to express our deep concern about the surge in discrimination and hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the currently inadequate federal response to address these racist and xenophobic attacks, a sharp break from the efforts of past administrations, Republican and Democratic alike,” the letter reads. Over the past month, there have been nearly 1,500 reported incidents of anti-Asian harassment and discrimination across the U.S., following an assessment by the FBI in March that found hate crime incidents against Asian Americans were likely to surge across the country.

This is followed by expressed disappointment at how the DOJ has responded since March. “Though this warning was issued more than a month ago, the Department of Justice has taken little action. In response the Center for Public Integrity’s inquiries about DOJ’s actions to address the increase in anti-Asian discrimination and hate crimes, DOJ pointed to an op-ed you published in the ‘Washington Examiner’ and a briefing call with Asian American advocacy groups. An op-ed and a briefing call are far from an adequate response from the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, whose stated purpose is to ‘uphold the civil and constitutional rights of all Americans, particularly some of the most vulnerable members of our society.’”

In an informative dig at the Trump administration, the letter cites the response during the George W. Bush era after the 9/11 terrorist attacks set off a wave of hate crimes targeting Arab, Muslim, Sikh and South Asian Americans. The Civil Rights Division at that time implemented a plan that included “a clear and plain statement to the American people that Arab, Muslim, Sikh, and South Asian Americans are Americans too; that hate crimes and discrimination against them would not be tolerated; outreach to the affected communities and coordination of civil rights enforcement across agencies at all levels of government.”

BASELINE VULNERABILITIES IN AMERICA

As has been noted in many contexts, due to the interconnected nature of epidemic spread, ignoring segments of the population who are most vulnerable to exposure and susceptible to disease puts the entire population at risk.

JoJo Jackson submits an informative post on his TikTok and Instagram accounts, @jojojaxn, about the Navajo reservation where he lives. To paraphrase: There have been 2,559 COVID-19 cases reported and 79 deaths as of May 5 on the reservation that spans more than 27,000 square miles, larger than the state of West Virginia. The number of cases on the reservation is nearly double the state of West Virginia’s, with far fewer hospitals (13 compared to 163) and grocery markets (six to 63) serving the reservation. At the end of April, when facing a severe outbreak of the virus, were the reservation a state it would have ranked no. 3 in the nation for cases and deaths, just below New York and New Jersey. Deemed statistically insignificant, “Native Americans continue to be left out of the U.S. data count on coronavirus and are categorized as Other.” “Native!? American,” Jackson says, emphatically. And of the 500 native tribes making up the country’s indigenous population, $8 billion in medical and general relief funding is being shared. “This is America,” Jackson signs off on the post, exasperated.

African Americans represent nearly a third of U.S. deaths from the coronavirus pandemic and 30 percent of COVID-19 cases, despite making up only 13 percent of the population. “This new development of what has happened with the pandemic with respect to African American communities … [is] perhaps an old development,” notes Evelynn Hammonds, chair of Harvard’s department of the history of science.

“So here we go again, carrying that theory forward of a kind of innate black pathology, an innate difference and deficit in black bodies that would be manifested in susceptibility and/or immunity to disease. Over time you see very little that dislodges that view, despite growing evidence of the role of social conditions in the production of disease or, as people now talk about, the social determinants of health.”

Rashad Robinson, for the “Guardian,” writes, “Deborah Gatewood was a black nurse who worked for 31 years in a Detroit hospital. Last weekend, she died from COVID-19 after being denied treatment by hospital doctors—four times. This fatal neglect may seem like a shocking individual story, but it is no surprise to those of us who have been tracking the many systemic inequities in health care for years.

“It’s the social conditions that continue to produce these vulnerabilities in certain populations, not that the people somehow are inherently biologically different. But, again, if you think about this in terms of the vulnerabilities that people have based on the social conditions that they live in, they may live in communities with high density, they may live in houses where there are lots of people living in small spaces, they may do work where they’re more exposed to something like a coronavirus. Those are the conditions that make them more vulnerable. It’s not that their bodies are somehow inherently different.”

Again, TikTok and Instagram prove adept at entertaining while distance learning. Consider user Uncle Lo’s (@lakewoodpapi) take on AAPI life. “The month of May is Asian Pacific Islander Heritage month. A month where we’re supposed to highlight AAPI history. And while I might sound ungrateful because minorities are just supposed to take whatever America gives them, no matter how inaccurate it is. But here’s the thing. Asians and Pacific Islanders are not the same people … that’s like having a Black/Hispanic option, those are two different, beautiful and important histories, why would you put them together? Here’s the problem with that, though. First of all, it teaches everyone that we’re all the same people but we’re not. Second of all it creates a misrepresentation of data and statistics when it comes to resources. Statistically, Asians do better in school, while Pacific Islanders tend to struggle. But in the eyes of data, AAPI is doing really well because Asians are doing really well. So no one helps the Islanders.”

A study from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Burns School of Medicine reports that the highest rate of COVID-19 exposure cases in several U.S. states, including Hawaiʻi, are found among Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Research shows as high as 217.7 cases per 100,000 in Native and Pacific Islander residents in at least five states—Hawaiʻi, California, Oregon, Utah and Washington. The rates of COVID-19 positive cases among Islanders exceed those reported for African American and Native American populations in the named states.

Data from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement indicate that 425 individuals in detention have tested positive for coronavirus. But only 705 detainees have received tests out of approximately 40,000 total individuals, making for slightly more than 1 percent of all detainees being tested for coronavirus. However, 60 percent of those have tested positive.

Cases have been reported in detention centers across 16 states including Michigan, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. In California, the American Civil Liberties Union filed suit against the state government on May 1, calling for an end to placing immigrants in detention centers during the pandemic. Specifically named in the suit is Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego, where some detainees say they are not able to maintain social distancing while imprisoned. “ICE has released nearly 700 individuals after evaluating their immigration history, criminal record, potential threat to public safety, flight risk and national security concerns,” according to the ICE website. A recent ruling in U.S. District Court has accounted for at least 250 detainees being released from Los Angeles’ Adelanto ICE Processing Center because of the possibility of the spread of coronavirus among the population. According to the lawsuit filed by the ACLU, small cells and a lack of personal protective equipment posed a contamination risk to individuals housed inside the center. Center officials are expected to comply with the orders by mid-May.

IN MORE CRIMES OF THE DAY

The pandemic has illuminated inequities tied to race in nearly every sector of society. For the majority of working people, and especially lower income service workers, the disparity is even more glaring. Of the 2 million AAPI essential workers, many are in the healthcare industry. They have seen their workplaces transformed by the virus into the most dangerous frontline combat zones, where they are staging an underfunded medical defence by donning paper armor against a largely unknown foe. The anti-Asian antagonism being fueled by political rhetoric has further raised levels of public fear, hostility and challenge to the work at hand.

The earliest days of the pandemic’s pillage across New York City tasked health care workers like Tre Kwon, an intensive care unit nurse at Mount Sinai West Hospital and a member of COVID-19 Frontline Workers Task Force. She returned to work early from maternity leave to support the pandemic response at her hospital. There, she not only faced the crush of critical care patients in the epicenter of New York and the nation’s epidemic as transport flew through their doors, but at the same time was disparaged by accusations from Administration 45 that New York hospitals were hoarding ventilators, supplies of personal protective equipment and other scarce life-saving equipment, by feigning shortages and patient overloads.

As staggeringly demoralizing a response as they faced, Kwon and fellow hospital workers pressed on, staging protests after completing hectic daylong shifts, and publicly taking to task one of the nation’s largest hospital chains and the blame-shifting federal government for lack of preparedness on behalf of patients and fellow health care and essential workers, whose rates of infection and death soared past national averages in the earliest days of pandemic.

Nurse Kwon and colleagues have been thrust into the frontlines of an economic race war that is playing out in the campaign hate rhetoric and policy bile spewed by our “American worker” protector-in-chief, who’s obsessed with restarting our economy while keeping silent on violence against wrongfully accused “carriers” of virus. Yet here they remain, after hours, organizing for safer working conditions, sizing up prospects for what is needed to build a better future. Hers and countless others’ are timeless stories torn from the pages of democracy today.

Like The Squad on Capitol Hill being told by 45 to go back to whence they came, we are already there-here. For indigenous, naturalized, permanent resident, documented and non-, asylum-seeking, ICE-detained: Home is where the heart is, Carlos Buloson wrote pre-H-2A visa, so to accede to an unwitting racist dog whistle only strengthens our resolve. This is our home.

In addition to providing low-cost farm produce under back-breaking conditions for the same unappreciative racists, history also relies on AAPI peoples to sacrifice yet more precious time and resolve contributing in their own way to dismantle the stranglehold race has on our democracy, by any means possibly eking us closer to a way of life that will be better and more democratic for those who come after us. That is what we believe it means to be a person of color, or an equality-minded human of any or no color, in America. What it is to be American. Okay, I’ll stop (stating the obvious).

And yet, these are extraordinary times, when it has become near impossible not to take a stand. Wade through a newsfeed for a moment and you’ll become a viral witness to not only widescale derision of global communities through normalized hate speech and political scapegoating, but also to heinous acts of violence that can and are taking lives, as in the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, only to be met with law enforcement indifference. These shrug-offs justice are lasting vestiges of the protection and service of a racial hierarchy upon which our country is built and remains clinging to a supremacist reign.

“A silent tongue does not betray its owner,” Sheikh Ahmed Hassoun, Sudanese mentor to Malcolm X, said in the best “no comment” paraphrasing ever to news reporters, on the eve of funeral rites for the assassinated human rights advocate. With this world-class rejoinder, we cut to the heart of race matters as projected by the mainstream media in 1965. Which I took to mean that nothing more need be said to reporters about Malcolm X, a man whose actions spoke for him.

Especially by a press corps who had proven to be invested in portraying the slain icon as an agitant force in the civil rights movement. Sheikh Hassoun knew the truth of it, having advised Malcolm X’s spiritual growth and pilgrimage to Mecca, which opened his thinking to a more humanitarian understanding of race and the world. He also knew how little the media there that night would relate to this experience, and did not try to persuade them otherwise.

Malcolm’s adherence to humanitarian values, including the right to self-determination and an evolving acceptance of equality among races, endeared him to a growing number of supporters and longtime friends, including Yuri and Bill Kochiyama, the vanguard of activists in the Asian American Movement and members of the pan-Africanist Organization of Afro American Unity.

The expanding consciousness among kindred racial groups would pose the biggest threat to the mainstream status quo, whose commitment to progress was limited to the incremental change represented by a more measured civil rights movement.

Sheikh Hassoun’s distrust of mainstream news in race matters remains relevant today as Attorney General William Barr and Admin 45 attempt to float their version of “history written by the winners” during an election year, with the help of a fractured news media whose own history is checkered with manufactured consent.

Again to quote Grace Lee Boggs: “Revolutions are when people reach the stage where they cannot continue to go along the same old way. And then they create something new. Being revolutionary is actually the beginning of something new.”

As a newspaper reporter during the L.A. riots in 1992, I was struck by the creative and acrobatic ways stories were framed to center people of color at odds with one another. Even as those same poc struggled, left alone to fend for themselves, against the institutional establishment. It taught me that what we see often depends on what you’re looking for. And the experience clearly revealed who benefits when minorities are divided by race.

The majority always comes out smelling roses. Add the stolen life of Breonna Taylor to the list.

And, once again, it is very much as Amy Winehouse sang: race, like Love, “is a losing game.”

In addendum: A modest proposal. I respectfully suggest a policy of categorizing, investigating and prosecuting racially motivated and other hate-based crimes as domestic terrorism. That includes extending domestic terrorism classifications to cover crimes committed by racial supremacist groups and individuals, and including state-sponsored, under-color-of-authority violence and obstruction of justice exhibited upon, to wit: the murder allegation of Ahmaud Arbery; the wrongful death of Breonna Taylor and numerous cases raised by Black Lives Matter advocates; quelling of peaceful protest by indigenous Sioux peoples of Standing Rock over encroachment by the Dakota pipeline development and its threat to water quality and supply in the region; and inclusion of hate crimes committed on religious groups at places of worship. Overall, a policy that defines white supremacy as domestic terrorism, carrying with it the same resources, government agency enforcement protocols and criminal sentencing guidelines as applied to combatting foreign terrorism. Just suggestions. Senators?

This article appeared in “Character Media”’s April/May 2020 issue. Check out our current e-magazine here.