Daniel Kim, a college senior, told his family he wouldn’t be coming home for Thanksgiving. Weeks later, he was dead. And the search for the unknowable began.

story by HELIN JUNG

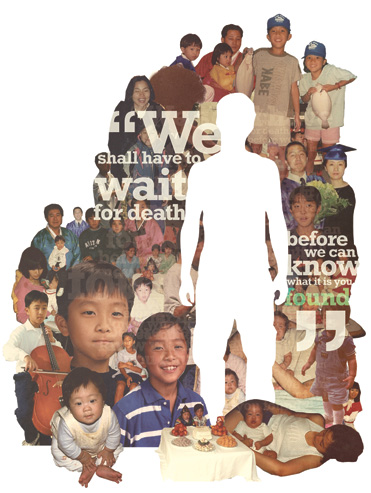

photo illustration by INKI CHO

Daniel Sun Kim sat in the driver’s seat of his black Hyundai Sonata on Dec. 9, 2007, gripping a semi-automatic Bersa Thunder Ultra Compact pistol in his hand. It was a Sunday, an unseasonably warm winter afternoon in Christians- burg, Va., a place known as the onetime home of Davy Crockett, the site of the state’s first recorded rifle duel. It is a city that touts “progressive small town living at its best.”

A 21-year-old senior at Virginia Tech, Daniel had come to this point be- fore—who knows how many times?— and here he was again.

In April of that year, another Korean American senior at V-Tech, 23-year-old Seung-Hui Cho, had also found himself contemplating the end, though not just his own. Cho took the path of infamy and extraordinary bloodshed, firing 170 shots across the university’s Blacksburg campus, killing 32 people and injuring 25 others in a spree that led to his disfiguring demise.

Eight months later, here Daniel was, alone, staring down the barrel of his gun. The car was parked outside a Target. Every bullet was in its place. This time around, he swore he would go through with it.

And he did.

From the very beginning, Daniel had been bright. Too bright, his father, William Kim, says. Like his father—who immigrated to the United States from Korea when he was 18—Daniel never studied, but that was of course because he never needed to. “There’s nothing for me to teach him,” a schoolteacher once told Daniel’ s parents. The homework got done and the grades were always better than middling, so Daniel’ s parents left him alone.

Instead, Daniel turned his heart-shaped face, with its wide and smoothly arched eyebrows, to the computer screen, because Daniel, called Danny by his school friends and family, found something more captivating in video games. He began with Nintendo as a boy and eventually graduated to more immersive gaming universes: Counter-Strike, a first-person shooter game involving terrorists and counter-terrorists; poker rooms like Full Tilt and Poker Stars; and World of Warcraft, a massively multiplayer online role-playing game in which zombies, trolls, orcs and dwarves wander destructively through fantastical realms. Danny usually played a warlock, a master of the dark arts who casts spells on his enemies.

His retreat into the virtual world was gradual. Even after the Kim family moved, in 1996, from New York City to the Washington, D.C., suburb of Reston, Va., Danny remained outgoing, especially as the playful big brother to beautiful Jeannette, the sister he adored.

Danny and Jeannette were a unit, two skinny kids so often left to fend for each other while their parents worked.In spite of being only two years younger, Jeannette relied on her oppa to be her protector. “When I was in elementary school, and I saw him at school, I was proud,” she says, recalling the way her brother was always nice to other children. As they grew older, the siblings became fixtures at their parents’ convenience store in Northwest D.C. In the summers, William could hear his daughter call out, “Stop! Stop! Dad!” as her brother teased her mercilessly from behind the register.

It was as a high school student that Danny “became shy,” according to William. He grew reserved, never saying much more than he had to. Outside of Danny’s already-formed circle, new people were annoyances, and he actively dismissed socializing with others at school and church. Even within that tight group of established friends, Danny never seemed entirely connected.

“It wasn’t your typical best-friend friendship,” says 26-year-old Kevin Yousefi, who was one of Danny’s closest friends in high school. They sat next to each other in every class, through four years of the International Baccalaureate curriculum. “I wouldn’t see him outside of school as much as you would think you would see your best friend outside of school. He was hard to get to go anywhere. I don’t think we ever even went to the mall together. He was at home on the computer—that’s who he was.”

Yousefi and Danny shared a fifth-period study hall, and both being inveterate underachievers, they would rush to finish their homework, then play hooky the rest of the hour by going home—Danny would sit at one of the two machines in his family’s dining-room-turned-computer-room— to play video games. At one point, the two friends were ranked third on the East Coast in Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos. They regularly stayed up gaming until 4 in the morning. What kept him out of trouble was that Danny could still pull through the next day and get a B on a test, though there were plenty of other afternoons “when we’d both be falling asleep in Spanish class,” Yousefi recalls.

The only time Danny seemed like a different person, and not the quiet introvert he was becoming, was when he was with the family dog, a Maltipoo named Amber. As often is the case with a household pet, Amber favored one Kim in particular, and that was Danny, who gave her treats and called out for her when she wasn’t near. Amber would sit in Danny’s lap when he was on the computer, and at night, she would be asleep in his room, not anyone else’s. “Danny wasn’t the most emotional guy, but he’d talk to the dog in a little baby voice,” Yousefi says. Even to Jeannette, seeing this softness in her brother was “weird.”

“With the dogs, he was able to show them,” she says. “It was sweet. Like he was a kid.”

Danny could be different, more expressive still, when he sat down at his computer.

When Danny was online, he went by Danimality, DK and It’s Big D Kim, the screen names he used in the various milieus of AOL Instant Messenger, a voice chat program called Ventrilo, and the games he favored. As DK, he was confident, quick with a joke, and with his unusually deep voice, he was even suave.

“When he was around, it was always a fun time,” says Garrett Green, 26, of Minneapolis. “I thought he was a pretty happy, funny guy. I thought everything was going great for him.”

“How he acted, how he talked, I thought for sure he was a really cool person to be around,” says Robby Morrison, 25. “He seemed sure of him- self. He made it seem like he was fine picking up females. It seemed to me like he did not have any issues making friends or getting along with anyone.”

In the five years that Morrison knew Danny, he never once saw his friend’s face, and though they lived just 20 minutes apart, they never met.

To the uninitiated, Danny’s gaming habits might have seemed extreme, but to his online peers, Danny was on the outer edges of submersion. Because he seemed to have a life outside his room. Because he seemed to have ambitions.

“Particularly within that community where, just realistically, there’ s not a ton of people really achieving a lot, this guy really had his sh-t together,” says Green. Danny was online regularly, but he wasn’t online all day. He was a math major at Virginia Tech, having switched out of the aerospace engineering track. Danny understood his program. He could talk about calculus with ease.

Not uncommon for young men his age, Danny liked to keep his hair cropped close to his head—it was low maintenance—and in the spring of 2007, he happened to cut it even shorter. His hair went from being a crew cut to a tight buzz. It was a style that Seung-Hui Cho had also adopted in the last year of his life. The images were disseminated across an unending loop of broadcasts. That disturbed, angry face, talking to the camera while wielding guns, knives and a hammer.

When Danny looked in the mirror, he saw a double. What the others must have seen in him, he thought, was the likeness of a killer.

“Do I look like the shooter?” Danny asked his sister in his usual joking manner.

“What are you talking about? You don’ t look anything like him.”

They had a laugh about it.

“I look like the guy who killed everybody,” he said to his roommate, Chris Crumpler.

“All Asians look the same to white people,” Crumpler responded snidely.

They had a laugh about it.

But one day in the summer of 2007, while in the elevator of West Ambler Johnson, which was Danny’ s residence hall at Tech and the site of the first series of shootings in the massacre, Danny was cornered and assaulted.

“He said, ‘Yeah, dude, I got my ass kicked the other day,’” recalls Kevin Yousefi, who was told of the incident over instant messenger. “He said he got into an elevator and there were white kids in the elevator, and they basically beat the crap out of him in the elevator.”

Danny started wearing a baseball cap and sunglasses when he left his room, which wasn’t for another two weeks after he got jumped, but he did not report the incident to school officials or his family.

Virginia Tech administrator Larry Hincker asserts that, “To the best of my knowledge, there was never any evidence that that was true. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. I had never heard of any instances of there having been a racially motivated assault on anyone in the Korean American community. Nobody was aware of anything like that.”

But sometime in 2007, perhaps in the summer, though it’s hard for any- one to say with any clarity these days, Danny stopped coming online as much. When he did, he would be drunk.

“I f-cking hate my life,” he would say in his intoxicated state.

“Nobody cares about me.”

He once complained about not having eaten in a while, so Garrett Green ordered a pizza for Danny and offered to visit him in Virginia. The pizza got delivered, but the trip never materialized.

Crumpler, himself a gaming enthusiast, didn’t feel concerned when his roommate stopped going to class and changed his sleep patterns. “His hygiene wasn’t bad,” Crumpler says. “He would come out, get food. Mostly he just stayed in his room. I didn’t think too much of it.”

When Danny went home in October to pick up his winter clothes, William noticed that his son’s face was covered in pimples and told him to see a dermatologist. “I didn’t think about it much,” William says. Danny then stopped answering William’s calls. But Danny had never given anyone any reason to worry, so mostly, William assumed that his son was having the time of his life. Senior year. All those parties. Life as a young man. When Danny finally called his father back, he said he was fine, and William believed him.

Shaun Pribush was up late on the night of Nov. 5, 2007, anguishing over what he should do about his World of Warcraft cohort. After trying to persuade his virtual teammate, essentially a stranger, that he was a “normal-looking guy” and that “he had his whole life ahead of him,” Pribush reached out for help.

Dear health center, This is serious email, this is not a joke. I am Shaun Pribush, a student at RPI, but I am emailing because me and some other individuals are very worried about our friend at Virginia Tech, Daniel Kim. Daniel has been acting very suicidal recently, purchasing a $200 pistol, and claiming he’ll go through with it. In one incident, he said on a Friday, he would do it after the weekend, but then told us he failed to go through with it. On about November 2, Daniel told me and friend over ‘instant messenger’ that he just swallowed 22 pills and said this is the end and signed off, but on the morning of November 5, he logged on saying “third time will be a charm I made myself puke up the pills when I was on the road and then I f-cking couldn’t shoot myself so then I was thinking about getting into a car accident then I got all depressed over that sh-t and slept in my car. Next time I won’t be a f-cking pussy.” We are very concerned for his safety are unsure the next time he might attempt suicide or go through with it, please forward this to who can give him the best care. Once again, this is very serious; this is not a joke. Please update me if you acknowledge this and take action so I know if I reached the right email address. Thank you

Standard operating procedure followed: Virginia Tech’s care team, upon isolating the Daniel Kim in question (there were six enrolled at the university at the time) and finding that he lived in off-campus housing, routed the wellness check to the Blacksburg Police Department. Officers knocked on the door of the two-story townhouse at Pheasant Run Court. Chris Crumpler, one of three occupants, answered the door, then went to get his roommate from upstairs. In what seemed like less than a minute, the interaction was over. Danny had told the officers that he did not know a Shaun Pribush, and that he was fine.

Sometime that same month, Jeannette sent an IM to her older brother, asking if he would be coming home for Thanksgiving. He said that he wouldn’t be.

Danny told his father that he was having car trouble, and though William knew that his son was lying, he didn’t push Danny to spend the holiday with his family. William couldn’t get a hold of his son in the weeks after Thanksgiving, so he called Crumpler, and finally got Danny on the phone.

“When are you going to come home?” William asked.

“Ten days,” was Danny’s reply.

“All right, you study hard, and I’ll see you in 10 days.”

What William could never have imagined was that it would be the last time he would speak to his son. “That was it,” William says. “He came home 10 days, exactly 10 days later. In a box. And I had no idea.”

William started a log following his son’s death. He titled it: “Events and calls following the worst moments of my life.”

Each new revelation is marked with the time it occurred (3:45 p.m. THE NEWS.). Some items are color-coded depending on their significance. He made hundreds of calls—to detectives, to university administrators, to the funeral home, to Danny’s friends. On Dec. 11, he went to pick up the Hyundai Sonata (It’s so tidy.) and the Bersa Thunder Ultra Compact (Daniel’s blood was still on it. Broke my heart.). After a panicked but brief search, he located Danny’ s cell phone; it had been in Danny’s pants pocket.

Nearly five years later, William, now 54, still has the cell phone and pays to keep it activated. It was only after three-and-a-half years that he was able to get rid of the car. Danny’s lap- top, a chunky black PC, sits on William’s desk in the back room of his convenience store. The computer re- mains closed, its secrets lost to corrupted hard drives and memory no more permanent in plastic than it is in the nervous system.

Danny’s mother, Elizabeth, processed the loss of her only son differently. She quickly went through and destroyed or disposed of nearly all of Danny’ s possessions. She converted his bedroom for her own use. One afternoon, while she was alone, she pulled every picture of Danny from the family’s photo albums and threw them away. She had his body cremated, after which she became a Buddhist. In April 2008, she took the ashes to Korea to have them spread on the grounds of a temple on Mt. Taebaek.

And while William threw himself into the pursuit of answers, eventually filing a wrongful death lawsuit against the commonwealth of Virginia for not attempting to notify the family when authorities were first alerted that Daniel might be suicidal, Elizabeth lost herself completely in her grief, waking her daughter each day with the sounds of mournful weeping.

“I’m still thinking about—even now I’m thinking as to why Danny died,” Elizabeth said through a translator in a deposition that took place Aug. 15, 2011. “I will think about that until the day I die.”

In December 2011, just after Christmas, Elizabeth and Jeannette took a four-hour bus ride from Seoul to Gyeongsangbuk-do to visit Temple Hyunbulsa, where the motto is, “Blossoming is not possible if there is no wind, and bearing fruit is not possible if there is no dew.”

The weather that week had been bitter cold, as winters in Korea are, and the rooftops of the temple’s pagodas were still covered in snow. On the day Elizabeth and Jeannette went to the temple, it was unusually warm. The sun was out. People were taking off their jackets as they walked up the steep hillside. “One of the monk ladies said that it was because oppa knew that mom was coming,” Jeannette wrote in an email to her father the next day. Other monks remarked that Danny must be bowing to his mother, who was brought to tears by the thought of her son’s still vibrant spirit.

Elizabeth and Jeannette spent the entire day at Hyunbulsa, participating in Buddhist rites, stopping at the hill- side where Danny’ s ashes had been spread and an evergreen tree planted to mark the spot.

Jeannette admits she joined the prayers out of obligation more than faith. Though she misses him profoundly and incontrovertibly, she is definitive about the fact that her brother is gone. She acknowledges that it was “strange that it was so warm on this one day. The next day was freezing. It could mean anything, really.”

Edouard Levé, a French photographer and author of the 2008 text Suicide, became an authority on the subject because he took his own life days after he delivered the manuscript of his last book. In it, he ruminates on the life of a young friend who killed himself long ago.

“You did not leave a letter to those close to you, explaining your death,” he writes. “Did you know why you wanted to die? If you did, why not write it down? Out of fatigue from living and disdain for leaving traces that would survive you? Or because the reasons that were pushing you to disappear seemed empty? Maybe you wanted to preserve the mystery of your death, thinking that nothing should be explained. Are there good reasons for committing suicide?

Those who survived you asked themselves these questions; they will not find answers.”

Like Levé’s subject, Danny left no note, and the traces he left, if they were once obscure, have since nearly vanished. As a young man who had not yet realized his dreams, who never knew great love or devastating personal tragedy, his was a life not yet formed.

The facts are uncertain, the reasons unknowable. There are merely fragments and flickers of possibility. Trying to get to the heart of a suicide always ends in failure, because the dead take their keys with them when they leave.

“We shall have to wait for death before we can know what it is you found,” Levé writes.

The lawsuit ended in a settlement in December, with Virginia Tech agreeing to establish a scholarship in Danny’s name. When the case ended, William finally had to face his grief, and the sadness bowled him over belatedly. To this day, he is angry, but, “At least I got something for his legacy,” William says. “We all live and die and nobody even knows that we were here. But the scholarship will be there forever, I hope. I hope that his name will be there forever.”

The latest entry in the diary that William keeps is dated May 28, 2012.

Daniel’s 26th birthday. Happy Birthday, Dan. I hope you are happy now wherever you are.

This article was published in the October 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the October issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only.)