Who Will Lead Korean America?

It’s a question that was heard 20 years ago, when Los Angeles burned and Korean Americans found themselves on the frontlines of the 1992 riots. It’s also one that resurfaces in 2012, as the country’s largest Korean American community faces new battles that could sure benefit from the voice of leadership.

story by JIMMY LEE

illustrations by INKI CHO

IN ARGUABLY the local story of the season, scores of Korean Americans converged on City Hall this past spring, and with their bright yellow “I Love K-town” T-shirts, literally lit up the august chambers of the Los Angeles City Council. They mobilized in numbers unheard of since the 1992 L.A. riots (World Cup soccer tournaments notwithstanding) and engaged in a political process that is as convoluted as it is controversial, no less: redistricting.

As members of the community, largely apathetic about civic affairs in the past, weighed in on how the city should reset its 15 council districts and, in some cases, complained loudly about all that was lacking in the city’s response to Koreatown needs, there were also whispers heard in these halls—that, at the end of this process, there would be a Korean American vying for a seat in one of these newly drawn council districts. The whispers proved partly true: Not just one person, and not just two, but three Korean Americans would eventually announce their candidacy for the 2013 race for the highly coveted Council District No. 13: John Choi, a former member of the city’s Board of Public Works; BongHwan Kim, general manager of the city’s Department of Neighborhood Empowerment; and L.A. Fire Department Deputy Chief Emile Mack. (As of this writing, Kim announced he was dropping out of the race to take a job in San Diego.)

Now instead of rallying behind one person to be the first Korean American elected to the Los Angeles City Council, we would have to choose.

Welcome to Los Angeles’ Koreatown, where it’s not uncommon for church members to splinter off and start their own church, and where there are often 10 chairmen of one board.

“We have a unity problem,” said David Ryu, a longtime local political staffer and one of the organizers in the Korean American community’s redistricting efforts. “There’s division because all the [community] leaders can’t agree.”

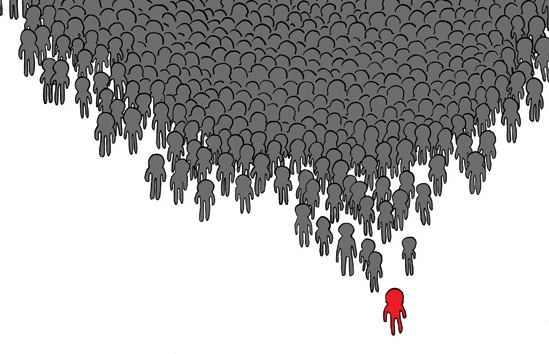

Rather, it’s a leadership vacuum that seems to continually afflict Korean Americans in Los Angeles. In 1992, we found ourselves being vilified during the L.A. riots. And throughout the burning, our community appeared alone, isolated from the rest of the city, hunkered down behind sandbags and shopping carts, while being besieged by not only looters but also the media and politicians, who showed little interest in understanding our plight.

Twenty years later, and amid the recent Koreatown redistricting fight, a question often heard in 1992 resurfaced amongst Korean Americans in Los Angeles: In this metropolis with the most Korean Americans and largest Koreatown in the country, who is our leader? Who is the person that will keep us from being scapegoated and caricatured if something like the riots should happen again? Who will guide us through a crisis if one were to erupt? The answer heard more often than any other: nobody.

FINDING PROMINENT individuals in the L.A. Korean American community is not a difficult proposition. There are successful businesspeople who hold a degree of stature in Koreatown, and the heads of the local Korean nonprofits are respected and regarded highly for their community service. The number of Korean Americans working in government positions continue to increase, all the while accumulating more influence in the city. With more of us firmly entrenched in multiple facets of Los Angeles life, many in the community agree that the targeting of Korean Americans as convenient villains can’t happen again as it did in 1992. We’ve grown up, and learned some lessons over the past two decades, namely, understanding how we fit into the fabric of this multiracial city.

But when it comes to identifying a figure who could be that singular source of leadership around whom the community could rally, there is no consensus. A few names do get thrown out there as possible candidates. But mention those persons as potential leaders to other people and be prepared to hear a litany of his or her perceived flaws. He’s too inexperienced. She’s abrasive. He’s arrogant. She’s too opportunistic.

In the words of the recently deceased Rodney King, “can’t we all just get along?” Instead, it’s as though we have a Pavlovian gag reflex programmed into us to immediately try to knock down anyone who’s achieved a modicum of recognition. So what the hell is wrong with us? Have all those years of our parents comparing us to Mr. and Mrs. Kim’s kids who got into Harvard conditioned us with the need to constantly one-up the other?

The problem is, this is a recurring theme in L.A.’s Korean American community. It happened to Angela Oh in 1992.

I REMEMBER being glued to my television, watching the chaos and mayhem of the riots play out in front of me. It was disturbing and painful to witness how Koreans were being characterized as rude shopkeepers and gun-toting vigilantes, as some Koreans armed themselves against the unchecked violence on the streets. For me, it was especially distressing and demoralizing, as I was the son of liquor storeowners, and the media had reduced me to both scapegoat and caricature.

But then, one night on ABC’s Nightline, appeared someone who spoke knowledgeably and resolutely on our plight. In college at the time, I had no clue who Angela Oh was. But she not only held her ground against Ted Koppel and his infamous argumentative interview style, she ascended to a role of leadership that Korean Americans like myself could look up to. Here was a person who knew the story of my parents and me, and she was defiant in presenting our case to a national audience.

“[Angela] became the voice of our community, and I think people really should provide some appreciation for the courage she demonstrated,” said Johng Ho Song, who was working for what in 1992 was called the Korean Youth Center and is now that same nonprofit’s executive director with its updated name, the Koreatown Youth and Community Center (KYCC). “She showed passion. And she felt the hurt that other people felt. She made a lot of comments that were needed at the policy level.”

Oh would be the person most identified with representing Korean Americans during the tumult of 1992. In fact, she would inspire a whole generation of Korean American young people after her appearance onNightline and her post-riots advocacy. However, after I started working at KYCC in 1994, I learned that others had a much different reaction to Oh’s emergence into the spotlight. “She was the voice to the mainstream, [but] not necessarily to the Korean American community,” said KYCC’s Song (disclosure: Song was formerly one of my bosses at KYCC).

Oh was subjected to barbs, primarily from first-generation Korean Americans, like: “she doesn’t really know anything about the Korean community,” or “how dare she become famous going on TV and pretending to represent us?”

“At that time, the criticism, I thought, was legitimate,” Oh told me, in an interview earlier this year. “Yeah, who am I? I’m just a lawyer in town.”

A criminal defense attorney born and raised in Southern California, Oh admitted her interaction with the Korean American community was minimal before 1992. But, at the time, she had recently been named the president-elect of the Korean American Bar Association. And what she did, once the flames were stoked, was to bravely face an unexpected and unwanted challenge—a trait expected from a leader. She ended up on Nightline because KABA’s president at the time apparently wasn’t comfortable with public speaking, so he asked Oh to go on the program.

“I guess I also felt like … I really understood how [the riots] all happened,” said Oh. “To this day, it’s interesting to me that some people in the Korean community really don’t see where they sit in the larger context of the population that lives here, the body politic, [and] the way in which the culture develops in the United States. And why would they? Many of them are first generation. They don’t know; they’re just trying to survive.”

It is the divide between the first generation—which in Los Angeles is largely a merchant class, owning and operating small businesses in Koreatown and throughout the region—and the 1.5 and second generations that has been a source of tension within the Korean American community over the years.

BongHwan Kim, a 1.5-er who grew up in New Jersey, was the executive director of KYCC during Saigu (further disclosure: Kim was also formerly one of my bosses at the nonprofit agency). Like Oh, he became a public figure, providing a Korean American perspective for the mainstream. And in the wake of the riots, when there were local neighborhood efforts to block the rebuilding of burned-down liquor stores in South Los Angeles (the liquor stores were often seen as magnets of crime and blight), KYCC created a program to help Korean American shop owners, who ran the majority of such liquor stores, convert them into other businesses, like laundromats. But to many Korean American owners, the mere suggestion that their stores shouldn’t be rebuilt was seen as an act of betrayal. Kim, too, heard critiques that he doesn’t represent Korean Americans.

“I think I was really working with the first generation as much as possible,” said Kim, recounting that time. “We were making joint decisions. I understand part of what [the first generation] perspective is, that I’m not one of them. I’m not a fluent Korean speaker. And I guess I wasn’t, from their perspective, authentic enough. And Angela even less so because she was second-generation. At least I was working in the community.”

The first generation is so often intensely focused on achieving financial success through their small businesses. They perceive that as their means of making it in America, along with the education of their children. That fierce dedication to their businesses is also what made it possible for Koreatown to be rebuilt after much of it was destroyed during Saigu, said William Min, 79, one of the first Korean Americans to practice law in Los Angeles. “[The first generation] has proven to be very productive,” said Min. “However, if it’s dealing with the external mainstream, that kind of contact, their skills are limited.”

The 1.5 and second generations, on the other hand, have a wider vision—one in which we play a larger role in American institutions and structures, such as in entertainment and politics. These differing desires can play out as competing interests, and it’s hard to fathom one person, one leader, being able to bridge this generational gap.

SOME MAY ASK: Why does the community need a leader? They may argue that we are too diverse for one person to be our voice. But in times of conflict and crisis, we can benefit from having someone who can bring a community together and mediate a consensus, others argue. This pro-leader camp cites the highly regarded Bill Watanabe, the former head of the nonprofit Little Tokyo Service Center, as an example of a person who fulfilled that role in L.A.’s Japanese American community for decades, up until his retirement in May. For Chinese Americans, they point to California state Controller John Chiang and Congresswoman Judy Chu as role models who the community can turn to for guidance and direction on issues. This type of figure simply does not exist for Korean Americans. And that was made abundantly clear in the recent battle over the new lines being drawn for L.A.’s 15 city council districts.

At a campaign stop earlier this year, Councilmember Eric Garcetti, one of the leading candidates for the 2013 mayoral election, summed up this year’s Korean American redistricting effort—sometimes dubbed the “Koreatown Spring”—this way: “Some have said, ‘We want to be in one single council district.’ Others have said, ‘We want as much of this neighborhood council boundary to be in a single council district.’ Others have said, ‘There’s certain councilmembers who we want to be with, and other ones we don’t want to be with.’ And other times, that ‘We wanted to have opportunities, areas for Asian Pacific Islander candidates or Korean American candidates to run and win.’ So those aren’t always the same thing, and one of the things I respect about the Korean community is that it is an incredibly diverse community with diverse opinions.”

Of course, the politician provided the positive spin. But another interpretation of Garcetti’s remarks is that Korean Americans were disorganized and disjointed in the redistricting fight. At one point, very early in the redistricting process, a majority of Korean American organizations, representing both first and second generations, commonly supported the idea of having Koreatown in a single council district, instead of the three or four it had been broken up into. That unified front quickly evaporated when some of the activists decided to attack Council member Herb Wesson, whose 10th council district encompasses much of Koreatown and whose administration had been accused of taking Koreatown money for his campaign offers, yet not responding to the neighborhood’s needs. (Incidentally, it is largely the first-generation entrepreneurs who are willing to take such shortcuts, like giving campaign contributions to politicians, which they believe will help ensure their businesses’ success.) As the debate evolved, there lacked a clear consensus as to what the community’s goal was, and that resulted in what appeared to many as the absence of a coherent, unified message.

“Going to [the redistricting] hearings in the beginning, we never knew what we could get out of them,” said Alex Cha, a Koreatown-based attorney who was a part of the redistricting organizing efforts. “We were so tired of being in four separate districts. So we were shortsighted. We didn’t know what kind of noise we could make.”

Eventually, members of the community did coalesce behind the idea of filing a lawsuit against the city of Los Angeles, should L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa sign the ordinance approving the new district boundaries, which he is expected to do.

“For what it was, the community mobilized really well,” said BongHwan Kim, who announced in mid-July that he would be leaving his mayor-appointed position with L.A.’s Department of Neighborhood Empowerment, and abandoning his city council seat bid, to take a civic engagement job in San Diego. “But I think in order to get anything done effectively, you have to have both an inside game and an outside game. We didn’t have an inside game because we didn’t have any elected leaders that were closely tied to the community.”

TO MANY in the community, the existence of a Korean American leader translates into having a person who can get elected to public office. “When I read KoreAm, it would feature KAs elected nationally, mayors [of various cities]. But we’re not hearing about anything coming out of Los Angeles,” said Sam Joo, the director of Community Services at KYCC. In this city with this sizable Korean American population, Joo asked: “Why is it so difficult for us to create an infrastructure to groom future leadership?”

Sukhee Kang asks that same question. He has been elected councilman and mayor of the Orange County suburb of Irvine. And after getting past a primary vote in June, he will be one of two names on the November ballot for a seat in Congress. Kang’s own rise to leadership can be traced back to Saigu. “That night [when the L.A. riots started] actually changed my life,” he said. “It was a wake-up call to me that you, as a Korean American, need to step up. Rather than just sitting back and letting things go, you’ve got to do something about your own community.”

And now that he’s made that leap, he, like Joo, wishes there was an entity that could help his campaign.

Kang’s prescription: “We need organizations, something like the Committee of 100 in the Chinese American community, 100 Hundred Black Men of America, or AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee) for the Jewish community.” These organizations provide important campaign dollars to political candidates, but they also serve as gateways for members of their communities to advance in politics. It may sound narrow-minded to suggest that, in our multicultural 21st-century society, Korean Americans should only support their own for political office, but the fact is there is a long history of more established ethnic communities providing this kind of support and foundation-building.

Maybe if there was an organization like that for Korean Americans, we wouldn’t have the predicament now forming in the race for City Council District 13, the seat being vacated by Eric Garcetti. After so many years of pining for a legitimate Korean American contender to run for city office, now we’ve got two in the same contest, and there are expected to be at least another 10 people running for this seat.

Of course, there’s no denying Emile Mack or John Choi his right to run for office.

But it’s not unheard of in some ethnic communities in which an established old guard will tell the young up-and-comer: “Maybe you should wait. It’s not your turn. We’ll get behind you a few years down the road.”

In Los Angeles, there hasn’t been the historic leadership to even have an old guard. Instead, it seems we have our community falling back on that old pattern of one-upmanship. The results are likely to be the splitting of the vote, and more years of waiting for that unifying Korean American leader to arise.

This article was published in the August 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today!