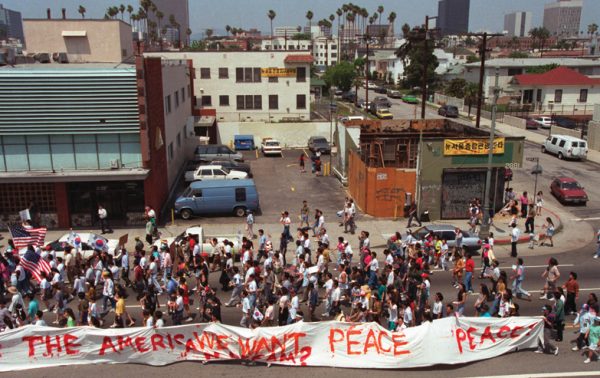

A view of Vermont Avenue in Koreatown, with smoke clouds in the background. ©HYUNGWON KANG

SAIGU: AN ORAL HISTORY

KoreAm retraces the days and nights of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, a defining event in Korean America’s collective history.

by EUGENE YI

additional interviews by K.W. Lee, Julie Ha, John H. Lee, Paula Daniels, Alex Ko, Katherine Yungmee Kim, Sophia Kim and Emily Kim

The events of April 29, 1992, have been referred to as a riot, a rebellion, an uprising, a civil unrest. For many Koreans, it’s always been 4.29, following the standard cultural shorthand for the dates of historic tragedies. Yet over the past 20 years, the primary narrative of 4.29 has rarely included Korean American perspectives beyond stereotyped notions of victims or vigilantes. This oral history seeks to rectify that in some small measure, and to give those who didn’t witness the traumatic days and nights of fires, chaos and violence a sense of what Korean Americans went through. The events, after all, have been referred to by some as the birth of Korean America, a characterization that isn’t far off.

In the period leading up to 4.29, the mainstream media had fed the public a series of stories on the rising tensions in South Central Los Angeles between African American residents and the Korean merchant class that had become a fixture there. Then, in March 1991, Soon Ja Du, a Korean immigrant storeowner, shot and killed Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old African American customer, following a violent scuffle between the two at Du’s South Central liquor store, worsening an already strained situation. Just 13 days earlier, the brutal beating of African American motorist Rodney King by four white Los Angeles Police Department officers vividly demonstrated the iron-fisted tactics under then-Chief Daryl Gates. The social, economic and political structures seemed aligned to oppress, and the city waited uneasily on April 29, 1992, for the verdict in the excessive force case against the police officers who beat King.

(Editor’s Note: The titles of subjects in the narrative reflect their age and status in April 1992. Organization names are based on what they were called in 1992. *Quotes indicated by asterisks were translated from Korean.)

April 29, Wednesday

I. RIPE TO EXPLODE

JET LEE

Owner of a liquor store in Compton

In everybody’s mind, it was ripe. To be explode. [My customers] were telling me, “Be careful.” One of my customers came [the] day before 4.29 and said, “Don’t stay open too late tomorrow. And listen to the radio, what they gonna say about the verdict.”

RAPHAEL HONG

UCLA student

Even before the verdicts came out, some younger blacks were coming in [to my parents’ toy store in an Inglewood swap meet] and saying, [if the LAPD officers are found not guilty,] “You guys better leave this town or else you guys are going to be in trouble.” Everybody [in my family] was already tense and kind of worried, so what they did was lose the doors early, and they went home.

BONG HWAN KIM

Executive director of the Korean Youth Center

I’d been involved in [a community group called the Black-Korean Alliance] for two years prior to Saigu. So the day of the verdicts, we all knew everybody was just waiting.

EDWARD CHANG

Ethnic studies professor, Cal Poly Pomona

Cal Poly was having an inauguration ceremony for their new president in the afternoon, and when it was over I walked into my office, and that’s when the telephone rang. On the other line was a reporter from a Korean newspaper, and she asked me, “What do you think?” “What do you mean what do I think?” And she said, “Not guilty.” “Wow. It’s going to be a major problem.”

II. ACQUITTED

At 3:15 p.m., three of the LAPD officers were acquitted, and one was partially acquitted. Unruly crowds chanted “No justice, no peace!” around Parker Center, LAPD’s headquarters, as well as the courthouse where the verdict was issued, and the intersection of Florence and Normandie, in South Central Los Angeles. Violence erupted. Mobs dragged motorists out of their cars and beat them. Looting began.

JAY LEE*

Owner of a furniture store on Florence and Normandie

[Crowds swarmed his store, and he hid in the attic with his co-workers.]

They broke glass table tops, carried off ensembles, capped off gunshots. I could see it all from my vantage point. … It was incredible. I told [my wife] to close up [her clothing] shop and go home. “Call the police and tell them we are trapped.” … We hid for three hours while people laughed and stole and rioted. That whole time, I kept thinking the police were coming.

HYUNGWON KANG

Photographer, Los Angeles Times, South Bay bureau

I distinctly remember hearing the LAPD police scanner telling all LAPD patrol vehicles to evacuate the intersection of Florence and Normandie. They were no longer engaged in controlling or restoring order. They were ordering their officers to evacuate for their own safety.

JET LEE

Compton merchant

When I heard that the verdict [was] not guilty, I said, “Shit.” Excuse my language, that’s exactly what I said. I had a kind of fear it might happen like this. I called all my relatives to get the hell out of there. I closed my store down, and on the way home, I heard the news that [at] Normandie and Florence, [an] incident was going on.

HYUNGWON KANG

Photographer

Someone hit my right rear window with a beer bottle. I was on Florence, going eastbound. The intersection was messy with debris rioters threw on the pavement. Shortly afterwards, other people on the sidewalk also started walking towards my car. As I was pulling away from the intersection, there was a call for help on the company radio—[Times photographer] Kirk McCoy was stranded, away from his car.

After receiving Kirk’s location from [photographer] Bob Chamberlin, I had to re-enter the intersection to get to Kirk.

Looters were all over the road, blocking moving traffic and carrying boxes of liquor from the liquor store at the intersection. My car was again struck with beer bottles, two or three times. One looter pointed a finger at me and started chasing me. I drove on the opposite side of the road, went through the red light and outran the guy.

RICHARD CHOI*

Announcer for Radio Korea, L.A.’s main Korean language station

I left work at 5 p.m. My home was in Pacific Palisades, so I took the 10 West, and I was listening to KFWB [an English language news station], and I heard a violent protest was starting. So I turned around and went back to work.

RAPHAEL HONG

UCLA student

My mother called [me at my apartment in West L.A.] and asked, “Is it going to really affect the business?” You know, she was really getting worried because that’s basically their livelihood. Both of [my parents] were working at the shop. I told them, “Don’t worry about it. I’m sure the National Guard will come—already they were talking about the National Guard [the first day of the riots]. So I told them, “Don’t worry about it.”

JIN-MOO CHUNG

Grocer and swap meet owner, South Central L.A.

Some guys, maybe four or five guys, they got a bat, some sticks. [They] suddenly came in and [started] breaking up all the glass, everything. We didn’t know why. [At the] time, we didn’t know.

DOROTHY PIRTLE

11-year-old South Central resident

I felt unsafe in my own house. Looters were throwing homemade firebombs into the windows of our local shops, taking everything from diapers and bottled water to shoes and stereos. From my room, I could hear glass shattering, people shouting, “No justice, no peace!” At first the sound of sirens answered the noise, and I held faith that someone was going to stop the chaos from enveloping us all. But when the sirens stopped blaring outside my window and I could no longer see police cars driving down Slauson Avenue, I knew that everything was beyond wrong.

BONG HWAN KIM

Korean Youth Center

The mayor had organized a town hall meeting in a black church in South L.A. And so I got together with a few folks working on the Black-Korean Alliance, and we drove down there. We started getting worried that it was packed, that there was no way we were going to get in. It was a good thing that we didn’t try to get closer because I heard later that people outside were actually beating up Koreans trying to get into the church.

III. SMOKE

JIN-MOO CHUNG*

Grocer, swap meet owner

A phone call came in from a friend. They said, “Hurry and close up. Riots have started.” So I did, and I told everyone from the swap meet to go home. I stayed, though. It wasn’t just my merchandise, but other people’s as well, and if the riots came, they would burn everything down. I stayed there, to try and do everything I could.

A fire rages near Manchester Avenue and Broadway in South Los Angeles. ©HYUNGWON KANG

A fire rages near Manchester Avenue and Broadway in South Los Angeles. ©HYUNGWON KANG

RICHARD CHOI*

Announcer, Radio Korea

Around 7 p.m., we started to get phone calls. Someone saying that “I’m at such and such intersection, a crowd of black people are gathering in the front of my store, and they seem threatening. What would be the best thing to do?” Before long, we thought, “Let’s just go live with the phone calls.” Because we started receiving too many phone calls. And because, for the Korean people listening to the broadcast, we needed to let them know what was happening. So we put callers on live, so they could say, “Something is happening. Be careful, be careful.”

RAPHAEL HONG

UCLA student

I’m [in my apartment] watching the news. My parents are watching at [their] home, and we were just communicating over the phone. Helicopters are flying over, and you see the burning buildings [on TV]. They flew by our [swap meet] building, you know, and, oh my God. That’s the swap meet. Some guy came, like a year before, and painted all the items that they sell in the swap meet. It says, “Inglewood Swap Meet,” and there was a hat, a jacket and toys and all kinds of stuff painted on there. I knew that was our building because of the painted walls. My parents kind of went into shock. They saw the building, and they lost everything. My father wanted to go to the store, and I said, “No way. Don’t get out of the house. Stay where you are. Don’t even go near L.A.”

I felt kind of guilty that I told them [earlier not to worry]. I said it because I believed it, first of all, and second, because I wanted them to relax because I was worried about their health. But once [the swap meet burned down], I felt really guilty. I shouldn’t have told them that.

JET LEE

Compton merchant

We came home, all my family got together and [was] watching TV. About 7 o’clock, my alarm company called. My father’s alarm company called. Everybody’s alarm company called. They said [they] got alarm going off. But we didn’t go because we knew what was going on. I called my employee, because he lives right across the street. And he was giving me eyewitness news on the phone. He said they started looting it, breaking [into] the store. A couple hours later he called me— it’s on fire.

JAY LEE

Furniture store owner

Somebody lit a bunk bed display on fire. Smoke choked me. I couldn’t see anything. I looked out and saw the house next door in flames. The display mattresses I left outside had been used as kindling. I just ran for my life. I told the first officer I saw, “There are two men trapped in my building. Help them!” The officer didn’t move. I ran to the next man and told him the same thing. I got the same non-response. I went to the next and the next. I begged five officers to do something. But nothing. Had I been able to speak English better, I would have told them to have courage.

SCOTT LEE

Student, El Camino Real High School

We were on the 101 Hollywood Freeway South when my friend, Rosa, pointed out that there was smoke coming out of L.A.

EMILE MACK

Firefighter

[My fiancée and I] were heading home, toward the evening, leaving downtown Los Angeles, heading down the Harbor Freeway. I looked off to our right, which would be looking west toward South Central Los Angeles, and I saw a column of smoke. And being a firefighter, I kind of went, “Hey. Hey. They have a fire.” And I said, “OK,” and we kept on going down the freeway. And then I saw another column of smoke.

IV. CHAOS

SCOTT LEE

Student, El Camino Real High School

The bus driver, Mr. Scott, told everyone to close his or her window. I dreaded getting off the bus. Two Hispanic gangsters rocked a big wooden platform, back and forth, until finally launching it through the glass window of a department store. A dozen or so people rushed in to ransack the now-open store. We arrived at my drop-off area, two blocks away from my house. As I exited, I tried to keep my head down and walked as fast as I could. It seemed like the longest two blocks I’d ever walked. People were throwing bottles at cars that were passing by. A guy got the crap beat out of him, and a dozen or so bystanders did nothing to help him. I passed the Radio Shack, movie theater, furniture stores. I turned the corner and saw a throng of about 400 people going in and out of the alley right behind my house.

The Los Angeles Fire Department received more than 5,000 structure fire calls during the riots. © HYUNGWON KANG

The Los Angeles Fire Department received more than 5,000 structure fire calls during the riots. © HYUNGWON KANG

JIN-MOO CHUNG

I was watching [people loot] from the second floor, and these people were not from the neighborhood. They were people I didn’t know. … I wanted to keep them from setting [the building] on fire, so I went down, with my gun, and I warned [them, in English], “OK, everybody, you taking all the merchandise, OK, no problem. OK? Don’t shoot. Don’t fire …” Then from somewhere, they shot me. Bullets, bang, bang, bang, they came in. And I was going to shoot, too. But that moment, I thought, “No. Don’t shoot. You’re not going to take a life away.” And, so—ach! I tossed my gun aside and fell to the floor.

SGT. LISA PHILLIPS

Los Angeles Police Department

We had a rescue. She was Asian, trying to get home. A crowd had surrounded her car and started beating her. When we got there, her car was encircled by rioters, two, three, four hundred people, people screaming, cars on fire, people trying to grab drivers out of their cars, running with TVs. We aimed the patrol car at the crowd, and people scattered. All but two: one guy on the hood had a two-by-four and was smashing in the windshield, and another guy had her by the shirt and was just pounding her. We ran up to her car. My partner, Dan Nee, grabbed her—she was bloody, strapped in with her seatbelt. We thought she was already dead.

We were running back to the car when my partner gets hit with a rock and goes down into the street. The woman goes flying out of his arms, and the crowd laughed. That is one thing I will never forget. The crowd spontaneously burst into laughter. It was hard not to let your anger go. As we were driving away this piece of concrete came flying through the car, completely exploding the window.

BONG HWAN KIM

I could never have anticipated that LAPD would just lose control like that. You assume that they’re ready. But they had no idea. Absolutely no plan to respond to the verdicts.

JIN-MOO CHUNG

Someone came in, and I thought it was more looters. But I looked, and they said, “Here!” And as I opened my eyes, I saw them. The police in riot gear. They said that someone had reported I had been shot. So the police raised my leg and said, “Don’t move.” They checked my pulse and said, “No problem.” They paged an ambulance for 40 or 50 minutes, and the ambulance didn’t come. And what’s supposed to happen to me then? My blood had all flown out.

RICHARD CHOI

Radio Korea

As 7 p.m. became 8, the phone lines were jammed. We just took the calls in the order they came in. No one was screening calls. We just answered the phone. So, as the broadcast kept going, we stopped airing ads, too.

ED CHANG

You began to see “This is a Black-Owned Store” signs everywhere to prevent rioters and looters from attacking their stores.

ANGELA OH

Criminal defense attorney, civil rights advocate

It was very specific to Koreans. Not to Chinese, not to Latinos. Not to African Americans. It was just really clear that it was specifically toward Koreans.

DET. BEN LEE

Los Angeles Police Department

If you had a liquor store, it didn’t matter if you were black, brown or Asian, they would attack you. You had black-owned businesses, but their businesses were attacked also. Unfortunately, Asians just had a lot of the stores in the area.

SCOTT LEE

Student, El Camino Real High School

They were looting the Radio Shack, furniture stores. I saw mothers and fathers with their children, some of who I’d figured to be about 9 years old, carrying large sofas topped with all kinds of electronic appliances that they’d just looted as a family. I was no longer scared and shocked. My blood was boiling. I made my way to my front door. I knocked and heard my father ask who it was. I said, “It’s me.” I entered my house to see my father ready with a bat to attack any intruder. We did not own firearms. The local news is playing on the television. All my family— cousins, grandparents, uncles and aunts—had come together.

JIN-MOO CHUNG

My head drooped, and the policeman said to his partner, “Let’s go!” They picked me up and put me in their patrol car. They lifted me up from both sides, and they took me and loaded me into the backseat. And we left. I didn’t know where we were going, but we were going to the hospital. That officer saved my life.

V. RESPONSE

MIKE WOO

13th District City of Los Angeles Councilmember

I was asked if I’d like to go down to the Emergency Operations Center, which was the room in the basement of City Hall East which is the nerve center of emergency operations. There were these telephones, computers, television screens, where information from trouble spots across the city is supposed to come in. What struck me was how unprepared the city was. I remember, there were these tables there with telephones, and there were these TV monitors on with the news of what was going on in the city. There was city staff sitting in the EOC who were hearing things on television, writing things on yellow Post-it notes, and attaching them to blackboards, to keep track of what was going on in the city. It told me that if the city staff were dependent on television news telling them what was going on in the real world, the system wasn’t working very well.

DET. BEN LEE

LAPD

The officers in the field, we were frustrated because we were not given direct orders to do what we needed to do, in essence to safeguard property, safeguard people’s safety. The management didn’t want us to inflame it more. If we went out there and took police action in an aggressive manner, the police were viewed as truly the bad guys. That’s the fine line we walked.

MIKE WOO

City Councilmember

The police response was reinforcing my unarticulated view that there needed to be a change at the top of the police department. I was concluding that under Chief [Daryl] Gates, the police department was not adequately prepared. There wasn’t an adequate plan about what to do. But during the days of the riots, there wasn’t very much I could do. Some people said the chief of police was more powerful than the mayor of Los Angeles. I think there was a kind of unspoken rule that nobody told Chief Gates what to do.

RICHARD CHOI

Radio Korea

Even at that point, a lot of people had closed up their stores and gone home because they were really worried. Someone would call and ask, “I’ve got a liquor store at 156th and Normandie, is my store OK?” And someone else would call and say, “I do business next to there, and the store is on fire.” And people would start crying and crying, “Oh no, what do I do? What should I do?”

JULIE CARL

9-year-old Koreatown resident

For the first time in my life, I heard middle-aged Korean men call Radio Korea and just cry.

RICHARD CHOI

Everybody was calling. We didn’t make an announcement about calling in. When I went on the air, I’d just say, “You should flee, in that case, you should flee.” At that point, everything we said was about fleeing. That was important. Don’t get hurt. I stayed up all night. I didn’t have time to think. It was crazy. As the night went on, everything started coming north.

EMILE MACK

Firefighter

We’re starting to get reports in that companies are already being attacked. And so we’re starting to get really concerned about what are we heading into. One of our things is we’re trying to get bulletproof vests. They don’t have any more at the shop. So I’m there, it’s midnight, it’s kind of lit with kind of a light that puts an amber haze glow over the yard as we’re starting to put our things on the fire trucks. And we get sent to our first fire.

DET. BEN LEE

The eerie sight of a glow of red in the horizon, and the smell of smoke everywhere. You couldn’t drive out of it.

A strip mall on Western Avenue and Sixth Street in Koreatown is overtaken by fire. © HYUNGWON KANG

A strip mall on Western Avenue and Sixth Street in Koreatown is overtaken by fire. © HYUNGWON KANG

CHUNGMI KIM

L.A. playwright

What I remember is the spooky, pinkish night sky.

April 30, Thursday

I. PROTECT OUR TOWN

RICHARD CHOI

Radio Korea

In the morning, the Hannam Chain supermarket owner Kee Whan Ha, he came to the radio station. And he took out his gun.

KEE WHAN HA

Owner of Hannam Chain, a Koreatown supermarket

I was so upset. It was small, a .45 or something like that. I took it to Radio Korea, to [Radio Korea president] Jang-hee Lee. I know him very well, we’re almost same age. We’re close to each other.

RICHARD CHOI

[Kee Whan Ha] said, “You keep telling people to flee, to go home, but how can we leave Koreatown? We came to this country and we worked like crazy and we made this town, our town. But if we leave, they’re going to burn it down. Don’t we have to protect our town? Can’t you say that on the radio?” And he offered to show us around so we could see what was going on. I couldn’t leave because I had to stay on the air, but Jang-hee Lee went out with Ha. And Lee came back and told Ha, “You’re right.”

KEE WHAN HA

So I went on radio, and I said, “Don’t go home. Protect your business. Your business is your life. All your rifles. All your weapons, bring everything out.”

RICHARD CHOI

I wondered legally how this would work out. Could we, while protecting our town, if something bad happens, could we have some liability? [Our lawyer] said, “You have a right and a duty to protect your property. In America, that’s why you have the right to bear arms.” So from 4/30, around 10 a.m., the message on the radio became: We have to protect our town.

EMILE MACK

We’d been working all night. We’re still in pursuit of vests. And where we’re sent to is the intersection of Vermont and 8th. That’s where we first entered Koreatown, and we began our firefight. We spot our hydrant that we’re going to hook up. It’s across the street, on the west side of Vermont, from the shops that are on fire. And just as we get off the fire truck to hook up our hose, we look up Vermont, and southbound on Vermont are two carloads of people. And they don’t draw any particular attention from us other than, there’s two cars traveling down the street. And the streets literally are deserted. And the two cars come out, and they stop in front of the shopping center, and eight, 10 people get out of the two cars. And they all line up on the sidewalk, pull out guns, and start shooting into the stores that are right behind us. And we immediately hit the ground. And then, as we’re watching, Korean storeowners start coming out of the stores while people in the cars are shooting at them. And they start shooting back.

RICHARD CHOI

The big shopping centers and stores had already been organizing [defense] before then. But they didn’t think shooting and all that would start. It was about showing that they would protect their stores. But once we started broadcasting that we should protect our town, then the thought that it was OK to shoot entered people’s minds.

HYUN SIK SONG

Member of Korean American Young Adult Team

I was listening to Radio Korea, and I heard announcements that people were gathering at Wilshire Tower Hotel to protect the stores. People began forming teams. There wasn’t a specific organizer, it just happened. We called ourselves the “Korean American Young Adult Team.” We were divided up into teams of 10, and we kept in touch through cell phones.

A security guard and other armed men protect California Market in Koreatown. © HYUNGWON KANG

A security guard and other armed men protect California Market in Koreatown. © HYUNGWON KANG

PETER LEE

Member of Korean American Young Adult Team

What got me mad when I was watching the news, it was live on TV, and the white newscaster was saying, “Look at these Koreans. What are they doing? How could they do such a thing?” I was like, what are you talking about? They’re defending their stores. The cops were just watching. That’s when I felt I needed to go in there and help out.

SONNY KANG

College student, member of Korean American Young Adult Team

Radio Korea was the lifeline for people in the community. People could call Radio Korea if they felt like they were in danger. Calling 911 wasn’t going to do anything. Radio Korea would put it on the airwaves: “A beauty salon on Beverly and Vermont, the windows are getting smashed in … is there anybody that can help?” We’d drive there as fast as we can.

JUNE LIM

13-year-old daughter of Gardena liquor store owner

My uncle had borrowed [a gun] from his friend, but my father refused to use it. Instead, he depended on brooms and my brother’s street hockey sticks for protection. My father stuck to his morals about not arming himself with a gun.

KEE WHAN HA

About 2 p.m., Koreatown was attacked by this mob. They were going on Vermont [heading] north. I own the Hannam Chain on Olympic Boulevard, and we assembled many people with [guns].

JENNY AN

Fifth-grader, Wilton Place Elementary School in Koreatown

During snack time, you see everybody running around, all the students, because they heard about the riots. It’s in L.A., oh my gosh! Everybody’s running around, everybody’s crying. My classroom was on the second floor, and I ran downstairs to tell my parents to pick me up right now. The phone line was so long. My best friend, I ran to her. I said, “Susie, what are we going to do? What are we going to do?” She said, “We’re going to die.” I just sat there and cried.

SONNY KANG

We basically had to fortify Korean businesses with rice bags, like sandbags in war. It was unlike anything you can ever imagine. Driving around Koreatown and seeing all these businesses with perimeters of rice bags, it was like a war zone.

KEE WHAN HA

One of our security guards [at Hannam], I met him in the morning. He’s a very good-looking guy, a French Jew. I said, “I’ve never seen such a good-looking security guard.” Suddenly I heard a loud bang. Many people started shooting with guns, with pistols. I saw his whole head going up, exploding. His body slowly coming down to ground without [a] head. I got so scared. Then he was gone. And I believe it was friendly fire.

EMILE MACK

They’re exchanging fire between the people from the cars and the Korean shop owners. [We] go around the corner, and then come back from north on Vermont. So when we come back, basically two minutes later, everyone’s gone. The cars are gone. The shopowners have disappeared, probably gone back into their shops. So as we began fighting the fire, I’m looking down Vermont, and within a few minutes, some stores in the next block on Vermont begin burning. And I really don’t see anyone, but I see the stores start burning on the next block. And then give it another five, 10 minutes, the next block after that starts burning. And over the course of the next few hours, as we are sitting there on this one fire, fighting this store fire, as far as we could see down Vermont, the fire has progressed with people setting stores on fire, businesses, all the way as far as we could see down Vermont to the Santa Monica Freeway.

HYUNGWON KANG

Photographer

California Market on 4th and Western was under attack. When I went there, I saw the owner of the shop with his semi-automatic pistol shooting into the air to fend off potential looters who were throwing Molotov cocktails to burn some of the shops. On 6th and Western—that shopping mall was already being torched. This California Market was trying to survive that attack. That’s when I realized that Korean Americans were being targeted.

HYE KO*

Owner of Koreatown video store

[My husband Hyung] said the rioters were coming and that things were very bad