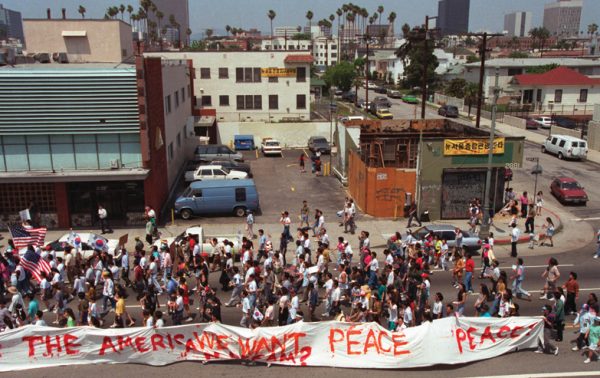

Photo credit: Hyungwon Kang

Reflections, 20 Years Out

Views on what’s changed in the past two decades and what hasn’t.

Raising Consciousness

“I think the most important lesson is the system took advantage of the fact that we didn’t have an articulate voice to speak out against the scapegoating going on. Because of that, it seemed like the media was basically allowing the Korean community to take the blame for all the injustice happening to blacks. The message today is: When we’re being targeted or scapegoated for something that isn’t right, we need to speak up for ourselves, band together. You see that happening already. When the Jeremy Lin thing happened, with the “chink in the armor” [headline], the guy who wrote that got fired. You see the power of the Internet really carrying the power of the Asian American voice now. That’s something we didn’t have 20 years ago.

—Sonny Kang, actor and mixed martial arts instructor for inner city youth

Los Angeles’ Korean community, as we know it, started in the mid-1960s. And after about 30 years of that community, they were still living as Koreans in America. [The first generation] didn’t care about America. They thought of themselves as Koreans, not Americans. But after the L.A. riots, after that, people started thinking if they want to survive in America, we can’t just live as Koreans. We have to become Korean Americans. So after the riots, there was a lot of bad, but this was one good thing.

—Richard Choi, vice president of Radio Korea

I think that in 20 years, there’s been a tremendous amount of consciousness raised. [Saigu] highlighted for people the necessity of reconsidering their frame. Why do I think that? Because of all of the things that I know happened as a result. You have a whole bunch of young people who decided to go and do Asian American studies. And many theses [were] written about different aspects of what was happening in terms of L.A. in ’92, whether it’s race relations, whether it’s class-race intersections, whether it’s class-race-gender intersections, whether it’s Korean community development, whether it’s community economic development, whether it’s political engagement, whether it’s journalism, whether it’s creative arts, whether it’s understanding philanthropy, whether it’s running for political office. I could go on and on. Are we at the place we should be? Not even close. But it’s far better than it was in ’92.

—Angela Oh, attorney

Repeating History?

On April 29, 1992, I watched scenes of recklessness repeated throughout Los Angeles, and wondered, “Why are these people doing this?” But the uneasy feeling of knowing the answer loomed. I was a senior at UCLA living in an apartment near Santa Monica. I looked around at my modest comforts and saw that I was a long way from home. I was only about 30 minutes away from my family, but I was worlds apart from where I started my life in the San Fernando Gardens Housing Projects in Pacoima.

I turned back to the screen and looked more closely. I saw the disenfranchised lash out against any form of apparent wealth. Looters who could barely afford their basic needs took advantage. Store owners, fearing for their livelihood, tried mightily to protect the little they owned. It was the embodiment of people fighting over scraps.

Twenty years later I ask, “What have we learned?” After the collapse of the economy in 2008, due in large part to the practices of some unscrupulous business people, I fear that much of what was learned is forgotten. But there is hope. The Occupy Movements helped raise awareness of the disparity between the wealthiest 1 percent and everyone else. As the middle class continues to shrink, we can unite. Let’s focus our attention on that disparity rather than on each other. It’s not too late.

—Jaime Maldonado, public school teacher, Los Angeles

The immediate crisis faded fairly quickly. The violence and even the level of intensity of the African American vs. Korean American tensions were reduced. But I think part of the legacy is the city still doesn’t have a very good way of sharing responsibilities among a diverse range of ethnic groups. I don’t think we’re that much better prepared today than before to deal with interethnic tension.

—Mike Woo, dean of the College of Environmental Design at Cal Poly Pomona

My 20-year-old college daughter is a perennial reminder to me of how old the Los Angeles riots were; she was born 20 years ago on Sept. 21, 1992. I was pregnant with her when the riots happened. For her generation, Korean American culture and history is about K-pop, Korean drama, galbi houses and noraebang. It saddens me because so many have no idea about the fiery economic holocaust that shook their ethnic community 20 years ago. Today, Los Angeles Koreatown is economically alive and thriving. Like a phoenix, the community has risen from ashes and is now larger, more colorful and bustling with people from all corners of Southern California coming to shop, sing, eat and dance. But, at times when I drive through Koreatown, I feel a sense of regret and sadness that too many people don’t know what we went through 20 years ago. If people are not educated enough about what happened, how can we prevent history from repeating itself?

—Sophia Kim, public school teacher and children’s playwright, Los Angeles

In the aftermath of the riots, I was sure that everyone would see the deeper damage wrought by racial and economic injustice and act to make things better so that an explosion like this would never happen again. In a strange way, I was proud that L.A., reputed for its diversity, prosperity and accommodation to dreams of every kind, had suddenly become a window into the stagnant soul of urban America and the warped state of the American dream. But I was hopeful exactly because at the same time, I really believed in L.A. as a fertile ground of reinvention. Here we could rebuild, repair and realize meaningful racial justice better and faster than other places because we had the capacity and the imagination. Anything could happen.

But almost nothing has, at least not for the black population whose anger about the Simi Valley verdict touched off 4.29. Black neighborhoods like Crenshaw have at best remained the same, as other neighborhoods and communities in L.A. have grown and modernized. Burned-out lots have gotten a gas station here, a government building there. Police relations have had a net improvement. But the fortunes of black people are actually declining, especially as demographics in South Central shift more to Latino and blacks become less visible. The hope I had in 1992 has settled into a kind of permanent defensiveness.

—Erin Aubry Kaplan, writer, Los Angeles

The Next Generation

If I were to talk to my sons about the riots, I would tell them that our society is organized according to economic opportunity. When people do not have access to opportunity to fend for themselves, by holding a job and providing for their families, there is something unjust about it. The L.A. riots was a byproduct of that reality, of our society’s neglect. I would tell them our responsibility is to look after everybody, including the disenfranchised. To know something and not to act on it is immoral. If you can help, you have to act.

—Hyungwon Kang, photo editor and photographer, Reuters

It just pains me to hear people say today that “it doesn’t affect me.” We need to take ownership of our community, our country. If you want to fix our country’s problems, own it. What are we going to do to make it better? That was the biggest part for the riots that I took away. That’s what young people need to know. We can’t equate it to slavery or genocide, but this was a pretty significant event for our community as a whole, and we need to say we’re not going to let it happen again.

—Candice Kim, attorney, Fullerton, Calif., who was involved in post-4.29 relief efforts assisting Korean American victims

This article was published in the April 2012 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today!