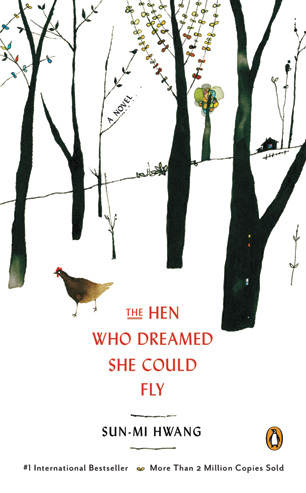

The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly

The best-selling Korean novel, marketed as “a Korean Charlotte’s Web,” loses something in translation

by ELAINE CHA

The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly is a novella I wanted to love. Since my time in Seoul from 2000 to 2002, I’ve longed for more English-language translations of contemporary Korean fiction. The discovery, therefore, of Hen—the Korean-to-English translation of Hwang Sun-Mi’s wildly popularMadang Eul Na-un Amtak—excited me as 1) a children’s lit lover, and 2) a heritage Korean speaker with very uneven reading and comprehension skills. Hen being hailed “a Korean Charlotte’s Web” stoked expectation. Comparisons to George Orwell’s Animal Farm intrigued.

And the prospect of being able to read the original—requiring a grade 5 level of reading, a good dictionary and some commitment—added to my anticipation.

[ad#336]

While Hen did not rise to the occasion, the fault may lie more in its marketing than its content. It was unpersuasive as children’s fare, by E.B. White or kid standards. But as a work for an older audience (or a serious, introspective pre-teen), The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly is, like its Korean original, an affecting tale offering much for consideration.

The Korean-language original, literally “The Hen That Comes Out of the Yard,” tells the story of Ip Sak (“leaf”), a common egg-laying farm hen who longs for two freedoms: hatching an egg to raise a chick, and escaping her cage. A series of events gives the hen opportunity to mother a little one beyond the farm, resulting in joy, discovery and peril. Ultimately, though, will does not defeat nature; the book’s end is Ip Sak’s, too, at once fulfilling the name she took for herself (in honor of the leaf’s power to bud, flower, fall and feed the next season’s foliage) and returning her to anonymity.

In Chi-Young Kim’s English translation, The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly, Ip Sak becomes Sprout, a hen “who want[s] to do something with her life, just like the sprouts on the acacia tree … she’[s] named herself after.” While Sprout’s life trajectory inside and away from the farmyard mirrors Ip Sak’s, what’s different—the book title, the hen’s name and a certain characterization of Sprout’s existential longing (Hwang writes that Ip Sak wants, like the acacia leaves, to do something, while Kim adds “with her life”)—is basic yet consequential: that, along with what’s missing by insertion rather than omission, is what makes Kim’s Hen an interpretation rather than a straightforward translation.

[ad#336]

As with any act of translation, communicating nuance is as much about the interpreter as it is about the interpreted. Kim, in the Korea Times response to criticism of her work with best-selling novelist Kyungsook Shin’s Please Look After Mom, described her method as “massaging [a] text to ensure that the person reading the translated text comes away with the same experience as a reader of the original text… A literal translation… fails the original work and the author’s intent.” That approach is obvious inHen, in early pages and throughout.

How successfully it captures Hwang’s intent or the original’s simple grace is less clear, especially when the translation elaborates upon Korean text whose plainness belies complexity (“눈물이 흘렀다. 암탉으로 태어나서 처음 흘린 눈물이었다.” becomes “Tears flowed freely from Sprout’s eyes for the first time in her life.”) This may be a complaint limited to a small bilingual contingent who will read both versions, though. Indeed, the translated novel has won over writers in high literary places, like Adam Johnson, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Orphan Master’s Son, who called Hen “a novel uniquely poised at the nexus of fable, philosophy, children’s literature and nature writing.” It may also be a consequence of imagining a contemporary youth readership with a markedly American cultural sensibility.

[ad#336]

Ultimately, The Hen Who Dreamed She Could Fly is worth picking up—as an adult read. Kim’s application of idiom and colloquial speech conveys the hen’s commonness; description of the solitary hen in the wild reflects Sprout’s spirit. For those who’ll read Hwang’s original, Kim’s version provides interpretation that’s sure to spark some serious talk about philosophy, society and cultural expectation. And for people invested in contemporary Korean work in translation, getting a copy may advance the cause of bringing more to an eager, English-dominant audience. In such respects, Hen fairly flies.

[ad#336]

This article was published in the March 2014 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the March issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only. Expect delivery in 5-7 business days).