The very word “Sahara” can conjure up a number of images, perhaps of gleaming artifacts from long-gone, exotic civilizations. Or of a vast, sandy emptiness, populated solely by camels and the occasional oasis. But many do have to wonder, even if idly: What’s really out there?

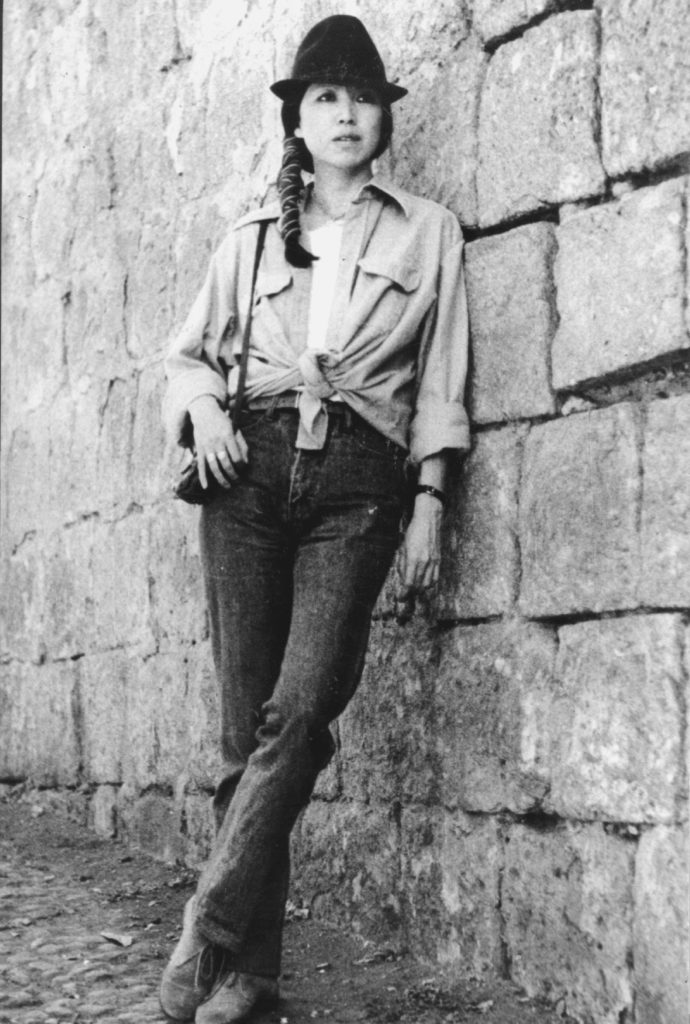

In the 1970s, Taiwanese translator and author Sanmao (born Chen Mao Ping) headed to Africa to find the answers for herself. Already having traveled and lived all over Europe, Sanmao moved to the Spanish-governed town of El Aaiún, accompanied by her husband, professional diver José María Quero. While staying in the desert, she published a series of essays in Taiwanese newspapers, illuminating the mysteries of the landscape and the lives of its people, the Sahrawi.

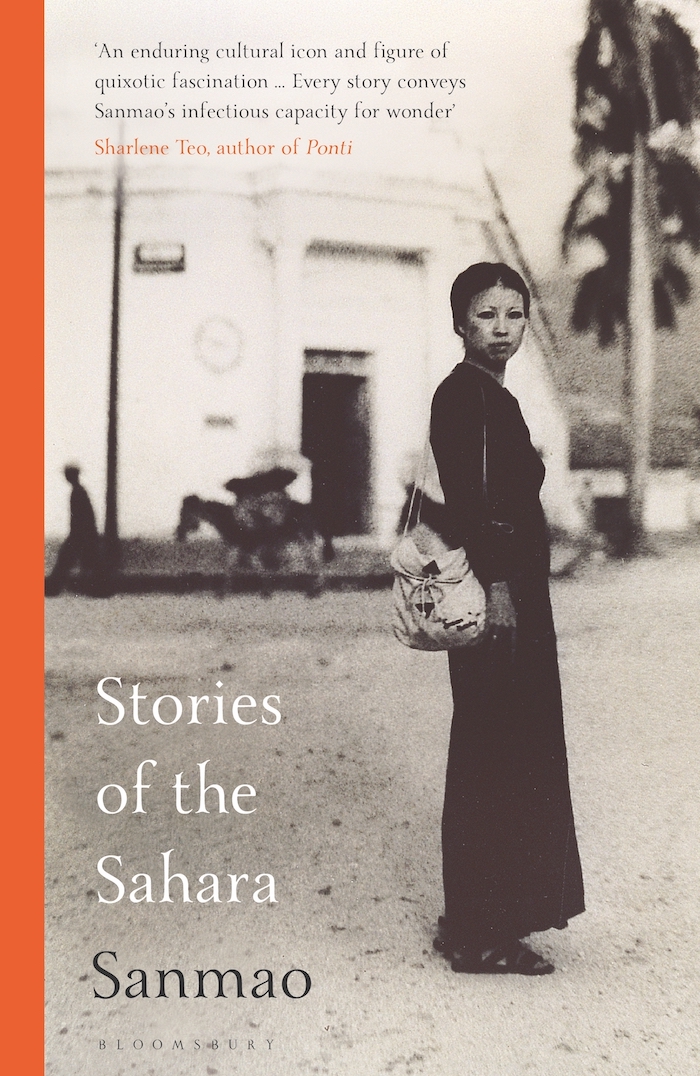

Those essays form “Stories of the Sahara,” beloved by readers throughout China and Taiwan, made available in English on Jan. 14. The collection gets off to a somewhat rocky start, because it becomes quickly apparent that no, these stories aren’t arranged in anything resembling chronological order. “Stories of the Sahara” instead jumps back and forth over Sanmao’s time in the desert, and at first that jumbled storyline might frustrate or confuse impatient readers. But once audiences are aware, reconstructing the disparate pieces of Sanmao’s life becomes much more rewarding than a simple beginning-to-end plot.

That level of engagement is also achieved by Sanmao’s writing style and translator Mike Fu’s work. Sanmao’s musings straddle the philosophical and practical, creating a contrast that brings to life a shrewdly resilient woman. Fu translates Sanmao’s words into spare, simple language, but retains poetic moments and literary allusions alike. “My Great Mother-in-Law,” the most tonally different piece from the rest of the collection, is full of obscure references, but they’re rendered so plainly that any reader can glean their meanings. Nobody will wonder if anything was lost in translation, because it’s impossible to imagine Sanmao speaking differently.

It’s equally impossible to not be endeared to Sanmao, as she remains open about both her triumphs and moments of vulnerability as she adjusts to living in the desert, surrounded by a foreign culture. In the essay “Hearth and Home,” detailing the first days of settling into her home in El Aaiún, Sanmao admits, “I was like a wounded animal during that time, taking offence at the tiniest of things. I was so low in spirits I’d often weep.” Though she later overcomes her loneliness to fall in love with the area and its inhabitants, she never romanticizes the Sahara beyond recognition, or lets us forget that the desert can at times be unbelievably cruel.

Over the course of the book, the stories begin to subtly transition from lighthearted, comedic accounts toward something much darker. During Sanmao’s time in the desert, the ever-present conflict between Spanish troops and desert natives escalated into armed conflict, leading to appalling acts of violence. But Sanmao mostly remains a bystander, faithfully recounting the atrocities she sees. Recalling a mute slave being sold away from his family, Sanmao writes, “His family members didn’t cry or scream. They held each other in a tight embrace, shrinking into the big red blanket like three stones formed in a sandstorm.” That plain, truthful reporting is part of what might make “Stories of the Sahara” difficult to stomach for some 21st-century readers. Sanmao doesn’t stray away from horrific tales of sexual assault and guerilla warfare, as painful as they may be to read and, certainly, as difficult as they were to write.

Sanmao eventually left the Sahara and returned to Spain with Quero, who later died in a diving accident. Heartbroken, she moved back to her homeland of Taiwan, where she committed suicide in 1991. Knowing her fate adds another layer of complexity to the reading experience of “Stories of the Sahara,” and could make one question whether it was her desert hardships that contributed in some way to her death. The collection never fully answers that, but more importantly, it revives the spirit of this international hero, and reminds us why she still symbolizes strength and adventure across the world.

This article appeared in “Character Media”’s Lunar New Year 2020 issue. Check out our current e-magazine here.