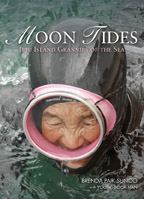

In her new book, journalist, writer and photographer Brenda Paik Sunoo documents Jeju Island’s renowned female divers. In the process, she finds surprising connections with, and inspiration from, these vibrant “grannies of the sea.”

by Katherine Yungmee Kim

photos by Brenda Paik Sunoo, from Moon Tides: Jeju Island Grannies of the Sea

On her first visit to South Korea in 1989, Brenda Paik Sunoo came across the haenyeo—the legendary women divers from Jeju-do. “How cool—feminist, non-traditional,” thought Sunoo, a third-generation Korean American who grew up in Los Angeles. She snapped a few photographs of “the rubber heads bobbing out of the water” and went on her way.

But a seed had been planted.

Twenty years later, she would return to the island, about 100 kilometers southeast of the Korean mainland. A seasoned journalist, writer and photographer by this time, Sunoo wasn’t content to be a passive observer. Though she’s long harbored a fear of the ocean depths, she lived and dove with the older haenyeo, some of whom work well into their 90s.

Her book, Moon Tides: Jeju Island Grannies of the Sea, released this month, is a testament to the strength and beauty of these women—to their physical prowess (they are reputed to dive up to 65 meters while holding their breath for almost two minutes); to their matriarchal livelihood (most learn their skills from following their mothers and grandmothers); and to their unparalleled relationship with the sea.

The haenyeo follow the tides, diving 15 days out of the month for seaweed and shellfish, and when they are not in the ocean, they are farming flowers, onions, garlic and cabbage—much of the produce found in the Jeju marketplaces. The book combines Sunoo’s award-winning photographs with unembellished first-person haenyeo accounts.

The haenyeo follow the tides, diving 15 days out of the month for seaweed and shellfish, and when they are not in the ocean, they are farming flowers, onions, garlic and cabbage—much of the produce found in the Jeju marketplaces. The book combines Sunoo’s award-winning photographs with unembellished first-person haenyeo accounts.

“These are working women,” Sunoo emphasizes, explaining the simple, direct narrative voice in the text. “They don’t have the time to naval gaze and indulge in verbal masturbation. They cut to the chase.”

These assiduous women have dominated the diving industry in Jeju since the 16th century, due to numerous factors, including their physical proclivity to better withstanding sea pressures and temperatures than men and their historical role on the island as the family breadwinners. In the 1970s, there were approximately 15,000 haenyeo. By 2002, the number had whittled down to 5,600, with more than 50 percent being over the age of 60; 10 years from now, that figure will be halved. Many of them lived through the 1948 Jeju Uprising, a rebellion in which tens of thousands of civilians who were suspected to be communist sympathizers were killed by the South Korean army.

“Their life is definitely not to be glorified,” says Sunoo, 63, from her home in Irvine, California. “It is to be respected and appreciated. That’s basically what I wanted to do [with my book].”

Moon Tides also represents Sunoo’s homage to a strong female figure in her own life—her late maternal grandmother, originally from north Pyongyang who crossed the seas to America in 1913. Sunoo’s halmeoni, who lived with her family throughout her childhood in Los Angeles, possessed a “survival-driven ethos” that reminded Sunoo of the haenyeo—and perhaps even drew her to them. Ever since her second visit to Jeju-do in the mid-1990s, the journalist knew she wanted to document these halmeonis’ stories before they died.

That opportunity finally came in 2007 while Sunoo, who formerly worked as a reporter for the Los Angeles English edition of the Korea Times and as senior editor for the national Workforce Magazine, was living in Vietnam with her husband Jan. The couple settled there between 2002 and 2009, while he served as an industrial relations specialist for a United Nations agency. It was in Vietnam where Brenda would hone her photojournalism skills, which served her well when she set out to document the haenyeo.

That opportunity finally came in 2007 while Sunoo, who formerly worked as a reporter for the Los Angeles English edition of the Korea Times and as senior editor for the national Workforce Magazine, was living in Vietnam with her husband Jan. The couple settled there between 2002 and 2009, while he served as an industrial relations specialist for a United Nations agency. It was in Vietnam where Brenda would hone her photojournalism skills, which served her well when she set out to document the haenyeo.

From the outset, Sunoo—who traveled to Jeju Island on three separate trips in 2007, 2008 and 2009—knew she wanted Moon Tides to be far more comprehensive than the multitude of travel pieces on the island and the haenyeo. “They’re not in a zoo,” she

says emphatically. “People come and take pictures and leave. I liked to represent them in a multidimensional way and not just their rubber suits.” She also steered clear of an academic treatise, which many Korean feminist scholars have already written.

Teaming up with Young Sook Han, a professor of English at Jeju National University who was her interpreter and translator,and the Jeju Haenyeo Museum, she embedded herself for the first two trips in the village of Gimnyeong-ri on the northern side of the island. She tried to “experience” the women’s lives—in their homes, at shamanist ceremonies, during their diving excursions—and illuminated and interpreted “the aspects that seemed to clothe their lives.” The book features images that provide a jarring juxtaposition of vulnerability and resilience, of aging and vibrancy. There are close-ups of deeply creased, sun-etched lines in faces of the haenyeo. And then, there is the bright, blinding yellow of a rapeseed flower field in bloom. Some of her photos, sharp and colorful, won the Community Choice Award from the International Museum of Women last year.

Notably, it was during Sunoo’s 2008 trip to Jeju, while celebrating her hangap (the traditional Korean 60th birthday celebration) with a couple of girlfriends, that the book’s theme—of autumn and aging—started to materialize. Having resided in Hanoi, where the majority of citizens were born after 1975 and where she had been regarded as an elder, she instead found herself in Jeju surrounded by women in their 70s, 80s and 90s.

“There was something to lean on and look forward to,” Sunoo recounts. “Role models who were robust and energetic, and loud and sometimes in-your-face. I could relate to them.”

In Jeju-do, the author was considered young—a realization that helped cushion her shock of turning 60. Finding confidence in her wisdom and talents as an experienced writer and photographer, Sunoo was propelled by the message that regardless of one’s age, one’s life purpose can be “as continuous, undulating and infinite as the sea.”

• • •

Moon Tides marks Sunoo’s third book of what she views as a trilogy. Her first book, Seaweed and Shamans: Inheriting the Gifts of Grief is a collection of her personal essays interspersed with journal entries and illustrations by her younger son Tommy, who died suddenly in 1994 at the age of 16. She considers this book—a chronicle of heartbreak and healing—to be “more dear” to her and the “most special.” Its ability to comfort others who have experienced loss has been “a charm” that has given her tremendous personal and spiritual satisfaction.

Her second book, Vietnam Moment, documents her foray into photojournalism. She paired each stunning color image— mostly of the people of Vietnam—with Vietnamese proverbs, song lines and stanzas from folk poems. The breakdown—“Feminity and Solitude,” “Together,” “Spirituality,” “Simple Pleasures,” to name a few—represents classic Sunoo themes. Each work in this trilogy has marked a decade in her life: her 40s, 50s and 60s. Each represents a homeland: native, adopted and ancestral. Emotionally, the first was written in a state of pain, the second in a period of joy, and finally, the third out of curiosity and inspiration. “There is an arc,” she considers. “If you look at a healing or an aging journey, it evolves that way.”

Sunoo says she has always been drawn to the sea. As evident even by the titles of her books, she writes from the shorelines of California, Chile and Korea. She and her husband were in Phuket, Thailand, during the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. Among her favorite books is The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and one of her favorite films, The Big Blue, is about two free divers. Her astrological sign is Aquarius.

“There is a relationship to water that I am trying to understand,” she acknowledges. Part of the impetus behind Moon Tides was to accost her fear of the ocean depths. But so much more came from the experience. She relates an anecdote about a hitchhiker, one of the women divers whom she picked up one day and later befriended. This woman told her that upon their first meeting, she felt that they were twins in a previous life. Then, at their next appointment for an interview, the woman told her she had woken up crying that very morning. “I don’t know why,” this woman had said, “but before you came I had this wave of sadness.”

Sunoo told her that she had lost a son. And then this woman told her that she, too, had lost a son. To the sea—he had drowned. “There were so many waves of magic and connections,” she says of her experience in Jeju. Indeed, Sunoo, who is also a Reiki master and grief counselor, is attuned to the uncanny—to coincidences, meridians and surprises. And open to the world. At the time of this interview, she was en route to Vietnam and Korea, where she will promote her book, and later this fall, she plans to tandem bike with her husband from Passau, Germany, to Vienna, Austria.

She is grateful for the support provided by her publisher, Hyung-geun Kim, at the Korea-based Seoul Selection, which has published all three of her books. He once wrote that he hoped her work would promote understanding between cultures.

“Personally and professionally, he loves literature,” Sunoo says. “And his legacy is the books that he leaves behind.” But, perhaps, she is really speaking of someone else.