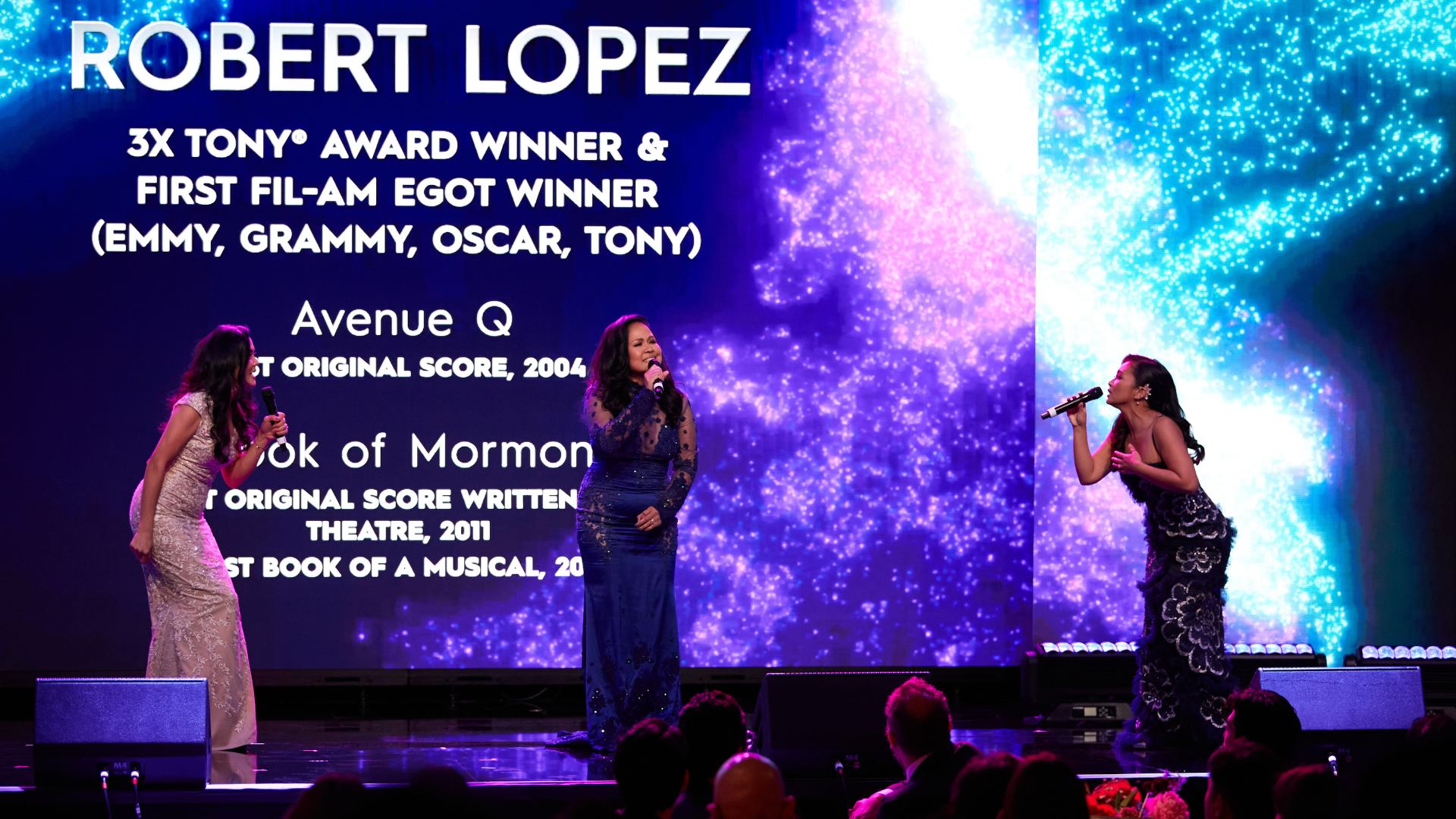

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak with President Barack Obama, June of 2009. (OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY PETE SOUZA.)

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak with President Barack Obama, June of 2009. (OFFICIAL WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY PETE SOUZA.)

Journalists’ rights group says, in well-wired South Korea, all is not necessarily well for freedom of the press

by Bob Dietz

Not surprisingly, North Korea—with no independent media—holds the title for the world’s most censored state, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a New York-based organization promoting press freedom and the rights of journalists. South Korea, with a wide-open press, seldom comes in for criticism. The high-tech, economic powerhouse is ranked as one of the most intensely wired nations in the world, and South Koreans enjoy near universal internet access. But all is not well with the media on the southern half of the Korean peninsula.

The South Korean news and human rights website Hankyoreh says the government could be heading for a dose of strong criticism from the office of Frank La Rue, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression. According to Hankyoreh, La Rue’s office will issue a report warning that freedom of expression has declined under President Lee Myung-bak. Hankyoreh said it was given an advance copy by an NGO source who had seen a copy of the report under the U.N.’s rules. Civil society organizations are allowed to make comments on draft versions of such U.N. reports. La Rue’s office declined to comment on Hankyoreh’s story when contacted by CPJ.

Two cases reportedly mentioned in La Rue’s draft relate directly to CPJ’s concerns. We at CPJ mentioned those cases and others in May 2009, when we wrote to President Lee to express our concern about growing pressure on journalists.

Blogger Park Dae-sung, who writes under the name Minerva, had angered officials by reporting that the government had tried to dissuade local bankers from buying U.S. dollars in 2008. An apparently self-taught economist, Park was widely read because so many of his predictions proved accurate. He was charged under the rarely used statute of “spreading false information with the intent of harming the public interest.” Though he was acquitted in April 2009, the case seemed an indicator of Lee’s attitude toward freedom of the press.

Another case said to be included in the U.N. report involves the 2009 arrest of television news producers for coverage that questioned the safety of U.S. beef. According to Hankyoreh, La Rue finds that criminal defamation complaints are being used to punish individuals who criticize the administration. La Rue is said to recommend that the crime of defamation be deleted from the criminal code.

In CPJ’s 2009 letter to Lee, we noted that South Korean journalists were harassed and threatened with prosecution if they travel to Afghanistan, Iraq or Somalia without prior permission from the Foreign Ministry. The government had criminalized such travel with punishment of up to one year in prison and a fine of up to 3 million won ($2,300). And in September 2010, there was a disturbing increase in censorship concerning North Korea, with the authorities forcing website operators to remove 42,787 pro-North Korean comments, The Korea Times reported.

According to U.N. protocol, the government of President Lee Myungbak gets to read the draft they received and offer their responses. (Here’s the most relevant excerpt from the published rules governing the procedure: “The draft report is first submitted to the Government to correct any misunderstandings or factual inaccuracies. Ideally, six weeks should be allowed for Government comments to be taken into account, but in any case no less than four weeks unless specifically agreed with the Government concerned.”)

The report is scheduled to be officially delivered to the United Nations Human Rights Council in June.

Since the end of military-controlled rule in 1987, South Korea has fluctuated between liberal and restrictive administrations. (Elections are due again in December 2012.) Under Lee, the country is in a period of media tightening; the government and its allies may push back against criticism from the special rapporteur. The government-funded Yonhap News Agency reported: “South Korea’s leading right-wing civic group said Saturday that it has sent a message to the United Nations, demanding that the world body review a U.N. expert’s report about South Korea’s declining freedom of expression.”

But restrictive news media policies are a bad fit for a country with the world’s 13th largest GDP and a per capita income of more than $30,000. Special Rapporteur La Rue might bring pressure to bear on the president to ease up on the country’s news media. La Rue’s report is scheduled for public release in May, and he will present his findings to the Human Rights Council in June.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Committee to Protect Journalists blog at cpj.org. Bob Dietz, coordinator of CPJ’s Asia Program, has reported across the continent for news outlets such as CNN and Asiaweek. Views expressed here represent those of the author and not necessarily those of KoreAm.