by JAMES S. KIM

Ju Hong didn’t learn about his immigration status until his senior year of high school when he was applying for college. As an undocumented immigrant, Hong recalled he had no idea how to apply for financial aid and what to put down for his nonexistent Social Security number.

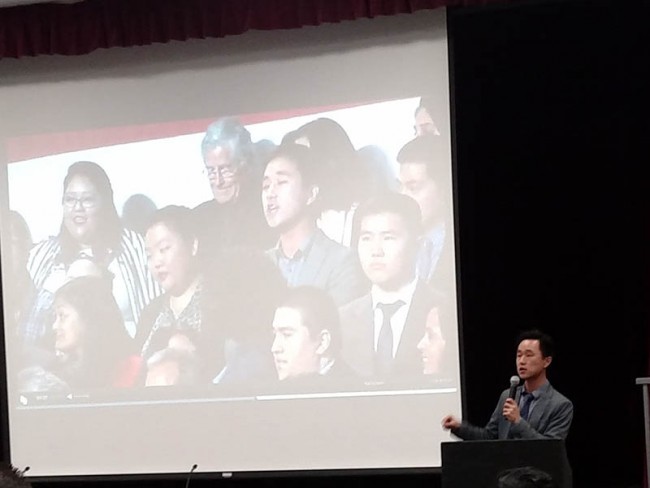

“I was ashamed of who I was,” Hong told students at California State University, Fullerton on Wednesday. “I didn’t want to be treated as an ‘illegal alien’ the media portrayed immigrant communities. … I felt isolated and embarrassed.”

Fortunately, Hong was able to find assistance through a Korean nonprofit. He was still able to apply for college and financial aid despite his status, and during his undergraduate years he took it upon himself to become an activist for immigration reform, which he said had a long way to go. It was his conviction that drove him to interrupt President Obama during a speech in San Francisco last year.

Hong encouraged students to be open-minded and keep learning about the issues. At the event, organized by Professor Eliza Noh of CSUF’s Asian American Studies Program, students were able to hear Hong’s testimony, as well as the perspectives of UC Irvine professor Gilbert Gonzalez and UCLA assistant professor Leisy J. Abrego. The professors gave brief histories of worker migration in Mexico and Central America, which were heavily affected by imperialistic U.S. business interests.

“I think this is a really great event,” Hong told KoreAm. “It brings different cultural community members to learn about this issue, and it challenges us to think critically about immigration system in the U.S. and internationally. It’s good to have a healthy debate on how to move forward and help undocumented immigrants.”

Immigration rights groups have been thinking more broadly and being more inclusive in recent years, according to Professor Abrego. Mainstream media has racialized the topic, leaving Asian Americans, for example, out of the discussion.

As a result, Abrego said organizations that worked with Latino immigrants were usually more up to date, more aware, and had greater access to resources — particularly when it came to accessing the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Established in 2012, DACA offers temporary relief from deportation and the right to apply for work authorization for undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children.

“We have a lot of Asian-Pacific Islander immigrants who qualify, but who aren’t applying in large numbers like it was expected,” Abrego explained. “Some of that has to do with how we portray the issue, and whether community organizations know that this is a need.”

Korean Americans are definitely among them. Hong, a research assistant at Harvard University’s National UnDACAmented Research Project, has made it a point to spread the word about the program, since many eligible undocumented Korean Americans haven’t taken advantage mainly due to lack of knowledge. Nonprofits involved in helping Korean Americans with DACA need greater support from the community, he said. He also said the Korean American community at large needs to vote and not be afraid to approach the issue.

“One last thing is to be really open-minded and learn about the issue,” Hong said, “rather than having judgmental or stereotypical perception of immigrants.”

That means cooperating and creating more spaces like this immigration panel, Abrego said. “The more we have these kinds of discussions, where we talk about the different groups, the more we recognize there’s not just one face to this. We need to understand the specificities but also the connections across the groups, especially [in] Southern California.”