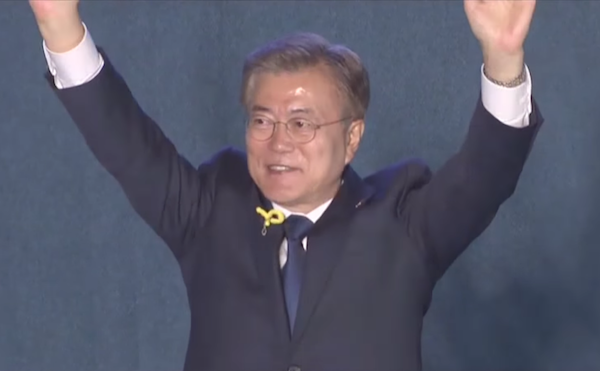

SEOUL — South Korea’s latest leader took office at an uneasy moment in his country’s history, inheriting the wreckage left by an ousted and excoriated predecessor. Among his lesser-noticed promises was a vow to improve quality of life in a society of long hours and hard work — to help break the chains to people’s desks, to let them take a breath and relax a bit.

And what Moon Jae-in preaches, it seems, he also practices. Even if, in the aftermath of North Korea launching its second ICBM, that means telling the leader of the free world: I’ll get back to you. I’m going on vacation for a week.

So while U.S. President Donald Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had an emergency phone call Monday, the South Korean leader’s office said Moon and Trump will likely talk after Moon enjoys some previously scheduled R&R, which ends this weekend.

It might seem an odd decision by a relatively new president in the midst of arguably the world’s biggest crisis, and certainly South Korea’s: Namely, North Korea’s march toward an arsenal of nuclear missiles, highlighted by its second ICBM test late Friday night.

But it fits nicely into Moon’s efforts to show South Koreans that it may actually help their work, not to mention the economy, to take a break from it — even if that work takes place at the highest levels of statesmanship.

It’s also part of Moon’s desire to draw, whenever possible, a clear line between himself and his currently jailed predecessor, conservative former President Park Geun-hye, who was seen as stiff, even imperial, and who now faces a corruption trial.

Moon, for instance, recently adopted a shelter dog rescued from possible slaughter, and last week orchestrated a carefully staged photo op that featured him in shirt sleeves hoisting beers with businessmen.

When Park’s dictator father led the country’s economic rise in the 1960s and ’70s after the destruction of the Korean War, working long hours and sacrificing time with family were seen as necessary to national success.

Even now, South Korea is near the top of the list of rich countries working the longest hours, and South Koreans reportedly only use about half of their annual paid leave days. Despite the long hours, however, the country’s reported labor productivity is relatively low.

Moon vowed to use all his vacation this year to set an example. He may also just want to take a break when everyone else does — or inspire those who don’t. The last week of July and first week of August, when schools are out, are when many South Koreans take holidays.

Though attitudes are changing, it is still considered taboo by many to leave work before your boss. A vacation by Moon, arguably the boss of bosses, amid all the pressures of his job, sends a powerful message.

“It has long been a habit to regard as a virtue burying oneself in work without going on a vacation,” the Seoul-based liberal Hankyoreh newspaper said in an editorial Sunday. “A president going on a summer vacation and using annual holiday can create an atmosphere where ordinary people rightfully go on their own vacations.”

The decision hasn’t been universally admired.

“The Korean Peninsula currently faces its worst-ever (security) situation,” Lee Jong-chul, a spokesman for the conservative opposition Bareun Party, said, according to the Yonhap news agency. “I wonder whether our people can understand why President Moon went on a vacation only a day after he responded to the North Korean provocation.”

U.S. presidents are also often criticized for going on vacation in the midst of the near-constant stream of crises they face. Golf is often the lure.

In Moon’s case, it’s not as if he’ll be sailing his way through some distant tropical archipelago. His holiday spot of choice is a military-run vacation facility in southern South Korea, where he can be debriefed and communicate with officials by teleconference in the event of North Korean provocations, his office says.

So, like so many of his fellow South Koreans — and their counterparts elsewhere — he’ll be going on vacation and bringing his work along with him, too.

By Foster Klug