Flipping through the children’s book “Drawn Together,” there are scenes that feel all too familiar. A young boy and his grandfather share a silent meal together. One diner picks at a plate piled high with hot dogs and French fries while the other quietly sips a bowl of ramen topped with a soft-boiled egg. Though they sit shoulder to shoulder on a couch watching TV, there’s an uneasiness between them. For Asian American kids with immigrant parents or grandparents, uncomfortable silences are just everyday fare.

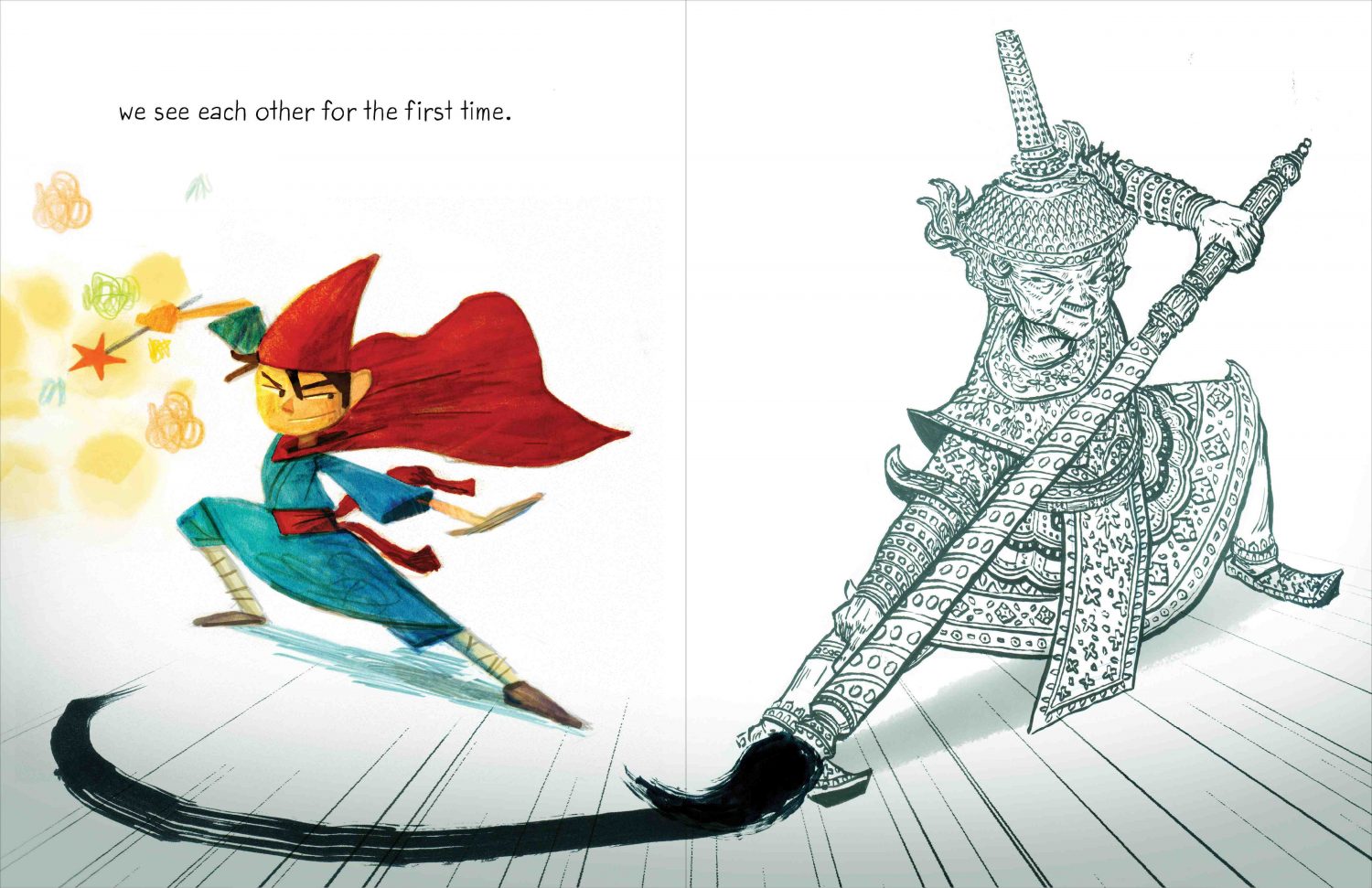

Author Minh Lê takes this premise and tells the story of how a young American boy and his Thai grandfather overcome language barriers and bond through a mutual love of art. Through the illustrations of Caldecott Award-winning artist Dan Santat, grandson and grandfather transform into a powerful wizard and a fierce warrior, respectively, and work together to conquer the distance between them. For its clever storytelling, “Drawn Together” has won a number of awards and accolades, including the Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association’s 2019 award for best picture book, for its ability to show that “despite generational and cultural obstacles, we can be drawn together.”

Though Lê didn’t intentionally make the book biographical, he and Santat both grew up with grandparents with whom they couldn’t speak. The scene where the boy and his grandfather sit together in silence is taken right out of Lê’s childhood. “My parents and my grandparents came over from Vietnam,” Lê said. “Vietnamese is actually my first language, but I lost it at about 4 years old. I wanted to capture this huge disconnect, but also all the love in the relationship.”

By day, Lê works as a federal childhood policy expert who helps low-income families access high-quality early childhood education, but authoring children’s books has always been his ultimate goal. “If you had asked me when I graduated from college what I wanted to do, my answer was to work in a small town library and write picture books,” Lê said. “The one thing in my core that I knew I had to go for was publishing children’s books.”

He achieved that goal of reaching young readers with his 2016 debut “Let Me Finish.” But Lê wasn’t able to share his latest with the one person he wanted to the most: his grandfather. Much like the young boy of “Drawn Together,” Lê just didn’t have the words to talk about such a personal project with him. And then before its publication, Lê’s grandfather fell into a coma. When the initial illustrations for the book came in, he printed them all out and made a mock version to take to his grandfather. He never woke up to see it.

“My hope was to be able to hand the book to him when I was done,” Lê said. “But it means a lot to me that he has a place on the shelf now. Working on this project has made him feel very present in my life, even though he’s passed. In a strange way, it’s made me feel even closer to him.”

When Lê goes to readings and school visits, people often tell him about their own similar stories of miscommunication. For Lê, the praise has been a way to help him come to terms with his relationship with his grandfather. “My failure to communicate with my grandparents was this big burden that I carried by myself,” Lê said. “But then to have people approach me and say how it resonates with them and their experience, … it’s like having my experience reflected onto other people. I felt a lot less alone.”