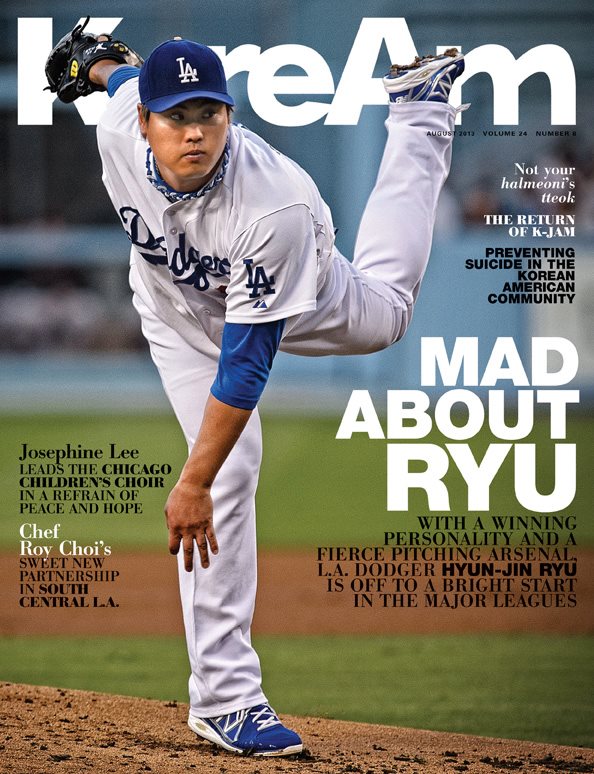

Dodgers rookie pitcher Hyun-Jin Ryu is the latest baseball export from Korea. But in his first season in the major leagues, he’s proving he’s got a style all his own. Even in the face of great expectations from his team, league, home country and newly adopted community on his shoulders, Ryu appears to be handling the pressure just fine—and even enjoying the ride.

by STEVE HAN

photos by MARK EDWARD HARRIS

On a breezy Saturday afternoon in June, Hyun-Jin Ryu stands face to face with this writer for an impromptu, long-sought-after interview in the corner of a private parking lot at Petco Park in San Diego, Calif. His bulging cheeks bathe sunlight, as he leans against a wall and cocks his head back. This is a rare sight, as typically, where there is Ryu, there are also hordes of Korean media surrounding him. He is, after all, the first Korean baseball player to go to the major leagues straight from the Korea Baseball Organization, where he was already a bona fide superstar.

But today, there are only Ryu, his interpreter Martin Kim and myself. Wearing a blue Dodgers sweatshirt and gray sweatpants, the 26-year-old appears relaxed; he’s not pitching today, the third game in a four-game series against the San Diego Padres. Then again, he almost always looks like this. On and off the field, Ryu—a hefty figure at 6-foot-2, 255 pounds—portends calm, cool and confident. So much so that early perceptions of him by the U.S. media and American baseball fans took that demeanor as cockiness.

Indeed, he had a rough early start. When spring training started in Arizona, sportswriters reported Ryu’s apparent lack of athleticism—he failed to keep up with his teammates in their first conditioning run. After a few days, he told Dodgers pitching coach Rick Honeycutt that he didn’t want to throw in bullpen sessions in between starts, which is a typical routine for major league starting pitchers. He even shrugged off advice from a Dodger legend. After observing Ryu’s pitching session, Sandy Koufax, a four-time World Series champion and a three-time Cy Young Award winner, gave the rookie tips on how to throw the curveball more effectively, to which Ryu said: “You always want to learn from the best, [but] just because it worked for Sandy Koufax, that doesn’t mean it will work for me.”

Then, in his debut on April 2 against the San Francisco Giants, the sold-out home crowd at Dodger Stadium booed him in unison for his lackadaisical baserunning in the sixth inning, after he hit a high chopper to third base and lollygagged it to first base.

Who was this rookie with the attitude? At that point, all Dodger fans knew was that this newcomer from Korea had cost the ballclub over $60 million. The Dodgers paid his former KBO team, the Hanwha Eagles, a $25.7 million fee just for the right to negotiate with the left-hander. Ryu’s six-year contract cost the franchise, which already boasts the highest payroll in baseball, an additional $36 million.

But, then, the narrative began to change. Before long, the jeers and skeptical sports columns were replaced by applause, cheers and praise from coaches, teammates and even opposing teams, as the pitcher, one game after another, showed who he really is. Although it would be expected for a rookie from a foreign league to take some time to get his feet wet in his new digs, Ryu has hit the mound running, impressing baseball veterans with his strong arsenal of pitches and ability to change speeds.

“He’s gotta be in the top 20, at least. Maybe even higher,” says Honeycutt, who during his own major league career was a two-time All-Star and World Series champion.

“He’s one of the upper echelon starters in the league,” says teammate Clayton Kershaw, the three-time All-Star and Cy Young Award winner.

And what some had earlier characterized in him as “swagger” changed to “relaxed” and “confident.”

Off the mound, teammates describe Ryu—nicknamed “Korean Monster”—as laid-back, well-liked and funny, adjectives not typically associated with previous ballplayers from Asia, who were more often deemed diligent and hardworking. Footage of him doing Psy’s “Gangnam Style” dance or bearhugging teammates in the dugout now crowd out the earlier jeering at Dodger Stadium.

“He’s always laughing and smiling,” says Dodgers manager Don Mattingly. “It’s just a little different from players I’ve had, like Hideki Matsui, Chien-Ming Wang and Chan Ho Park.”

Of course, the most predictable comparison would be to place Ryu alongside Park, the former Dodger who in 1994 emerged from Hanyang University and was the first Korean ballplayer to come to the major leagues. But, different from Park, whose goal seemed to be to put Korea on the MLB map, Ryu—part of the next-generation KBO who grew up watching Park play in the majors—is trying to go beyond that and prove that Korean ballplayers are formidable, that they can compete with and even beat the best. And that’s the narrative Ryu is trying to tell with every performance from the mound, and perhaps even with his seeming swagger.

“Everything is different,” Park told KoreAm last February, when asked to compare Ryu to himself in the early ’90s. “Ryu is already a proven player, but I was completely unproven. I had to develop in the minor leagues for the first few years. Ryu comes as a player who’s ready to make an immediate impact in the big leagues.”

As with Park, Ryu also carries the added expectations of not only his countrymen back home, but also of those Koreans in the U.S., who have quickly grown enamored with this baseballer with enormous potential. Heck, even the Korean Canadians have joined in the fervor, making headlines last month forregistering a rousing ovation for Ryu in Toronto.

And, with the Dodgers’ recent string of wins, the Korean Monster may even become the first Korean to start a game in the MLB playoffs.

In other words, the pressure’s on. Or is it?

“Personally, I’m not really feeling a whole lot of pressure,” says Ryu matter-of-factly. “Sure, there’s that pressure of having to represent Korean baseball, but there’s not much besides that.”

There he goes again. There’s that swagger.

Who raised this kid?

Born in Incheon, South Korea, Ryu is the son of Park Seungsoon and Ryu Jaichun. The junior Ryu’s competitive nature is often attributed to his father, who simultaneously mollycoddled and toughened him up during Ryu’s youth.

A former rugby player, Ryu Jaichun didn’t shy away from demanding disciplined athleticism from his son. He never scolded him for giving up home runs, says Hyun-Jin, but not throwing strikes, let alone walking batters, was unacceptable to the patriarch. Even at the expense of getting hit around, he wanted his son to throw pitches that would, at least, give the eight other field players a chance to make a play on the ball.

“I hated giving up walks since I was really young,” Ryu says. “It’s been ingrained in my head since then because my dad always told me, ‘You can give up home runs, but not walks.’ I think that’s what helped me to have the kind of control I have over my pitches now.”

As tough as he may have been, Ryu’s father did everything he could to help his son achieve his dream of being a professional ballplayer. “I never wanted to hear from anyone that my son couldn’t become a better player because I couldn’t do this or couldn’t do that for him when he was younger,” he told a Korean daily, the Kyunghyang Shinmun, after the Dodgers earned the rights to negotiate with Ryu.

What he did provide for his son included installing a net and surrounding lights atop the roof of the home where his family lived. This way, his son could practice pitching and batting at any time. Even though Hyun-Jin was naturally right-handed, his father bought him a left-handed glove and insisted that he throw with his opposite hand to have a unique edge over the abundance of right-handers in professional baseball.

But it wasn’t Ryu Jaichun who convinced his son to pursue baseball as a career; it was Hyun-Jin himself.

His childhood was a ritual of playing catch, watching instructional baseball videos and going to the ballpark to watch his hometown ballclub, the Hyundai Unicorns. If and when his father couldn’t take him to the nearby Sungui Baseball Stadium for a Unicorns game, Hyun-Jin pouted for days. Student protests against the government were still prevalent in Korea in the mid-’90s, and at times, Ryu’s father had to march through a smoke of tear gas with his son in his arms just to get to the ballpark. It was then that he started to wonder if baseball was his son’s destiny.

When Ryu started playing baseball competitively for Incheon Changyeong Elementary School, Chan Ho Park, then with the Dodgers, had already become Korea’s first-ever major leaguer. Ryu was only 14 when he was at home watching the 2001 MLB All-Star Game, where Park represented the National League. Park told KoreAm last February that his presence in the big leagues changed the complexion of Korean baseball because kids with aspirations of becoming professional ballplayers grew up watching baseball of the highest caliber on television. Park said those kids later went on to elevate Korean baseball. Ryu was one of those kids.

In the same year Park became an All-Star, Byung-Hyun Kim of the Arizona Diamondbacks became the first Korean to win a World Series. Unlike his predecessors in the major leagues, Ryu grew up knowing that his chance at the world’s biggest stage would come one day. He had the advantage of knowing that, not wondering if, Koreans are capable of competing with the world’s best.

***

And compete he has. At the All-Star break, the southpaw held a 7-3 record with a 3.09 ERA (earned run average) and 1.25 WHIP (walks plus hits per innings pitched). His 78-percent quality start rate—14 in 18 starts—puts him seventh in the National League among starting pitchers who have pitched over 100 innings by the break, only behind the likes of All-Stars Cliff Lee and Matt Harvey.

Throughout his first season, Ryu has also consistently shown something of a “clutch gene,” able to prevail in decisive moments.

In 116 2/3 innings Ryu pitched this season, opposing batters went only 18-for-87, a .206 batting average, with runners in scoring position. He also induced 16 double plays thus far this season, fourth highest in the NL. Eight of those 16 double plays came with runners in scoring position.

“I don’t really intend on getting batters to hit into double plays, actually,” Ryu says. “But batters realize that I don’t throw a lot of balls, so they’re aggressive with swinging the bat. So I just try to locate my pitches in the lower part of the strike zone, and that’s what led them to hit a lot of grounders for double plays.”

The defending world champion San Francisco Giants, the Dodgers’ fiercest rivals in the NL West, faced Ryu four times this season and pushed him around with a total of 30 hits. But besides one game in May in which they scored four runs, even the Giants, deemed Ryu’s “nemesis” by the Korean media, only combined for four earned runs in the other three meetings against Ryu.

“He’s shown an ability to pitch out of jams,” says Bruce Bochy, the Giants’ manager who led them to two World Series titles in the last three years. “He can pitch in traffic when he gets in trouble. He’s very confident out there. Our guys did a pretty good job of creating opportunities against him, but we couldn’t get a big hit.”

Honeycutt, the Dodgers’ pitching coach, has been so impressed with Ryu’s ability to get out of trouble that he compared his composure in clutch situations to that of the legendary Greg Maddux, a Hall of Famer, who won four straight Cy Young Awards between 1992 and 1995.

“Ryu just never gets rattled,” Honeycutt says. “At full count, he reminds me of Maddux. It doesn’t matter what situation he’s in. Even in games when he wasn’t at his best, he kept us in the game. That to me is a sign of a guy who doesn’t get flustered. You can’t really tell the difference in him no matter what’s going on. You just see that he has a different gear.”

What makes Ryu especially effective is his mastery of sequencing his pitches. His hard-soft-hard approach on the mound is essentially the baseball equivalent of a point guard’s fast-slow-fast dribble penetration in basketball games that tricks the opposing defense in the open court.

This approach was on full display at a May 28 game against the Los Angeles Angels, when he pitched his first shutout win, in just his 11th start. As Ryu held the Angels to just two hits en route to a 3-0 win, his four-seam fastball was clocked as high as 95 miles per hour, while the velocity of his curveball dropped to as low as 69.

Zack Greinke, a former Cy Young winner who signed a six-year, $147 million contract with the Dodgers in December, was apparently astounded at the beginning of the season by Ryu’s ability to change speeds, so much so that he approached Martin Kim, Ryu’s interpreter, to say that Ryu had become his favorite pitcher to watch.

Ryu is so confident in all four of his pitches—his fastball and curveball are complemented by a sharp slider and his signature changeup—that he doesn’t necessarily have a primary out pitch. In fact, he is the only active Dodgers pitcher to have thrown four pitches with regularity—at least 10 percent usage rate for each—this season. “I tend to do things on a game to game basis,” Ryu says. “I go with the pitch I have the best feel for on that particular day. Learning to make adjustments this way is what helped me to develop a four-pitch arsenal.”

And then there’s Ryu’s obsession with throwing strikes. Honeycutt points out that Ryu is almost too good at throwing strikes that, at times, his overreliance on it has actually worked against him.

“I’ve seen teams that get a lot of hits off of him [because] they go out there and get aggressive early, because they know he’ll be around the plate,” says Honeycutt. “That’s really been the only times you see him get hit around.”

Hunter Pence, outfielder for the San Francisco Giants, has capitalized on this, and Ryu considers Pence the toughest batter he has faced in the major leagues so far. Pence is 6-for-11 with five runs batted in against Ryu this season.

“But he’s still had some great success so far,” Pence says of Ryu. “He’s given up some hits to us, but I feel like he’s gotten a lot of double plays off of us at big times. He’s just an athlete, and he competes. He competes really well.”

***

When the Dodgers signed Ryu last December, there was already a buzz among Korean American baseball fans in Los Angeles and even across the country. Perhaps sensing this, even before Ryu threw his first pitch here, the Dodgers held an autograph signing in Los Angeles’ Koreatown. Ryu was also the only rookie to be present at the Dodgers’ annual fan fest in January.

“If you asked me three months ago, I would’ve said, ‘This is great for L.A.,’” said Martin Kim, manager of Korean Relations and Corporate Partnerships for the Dodgers. Also serving as Ryu’s interpreter, Kim can often be seen on the mound helping the pitcher communicate with coaches and teammates.

“But now that we’ve traveled to over 10 cities around the country, I can see firsthand how much hope he gives to the Korean American community,” continues Kim. “Just the things that people shout out to him, and even when we were in a small town like Milwaukee, there were at least 30 to 40 people who came out early just for him.”

In a way, Ryu’s barnstorming tour in the major leagues rekindles the memory of the cult following Chan Ho Park garnered from Korean Americans in the 1990s. After debuting in the major leagues with the Dodgers in 1994, Park went on to win 124 games over 17 years and was a National League All-Star in 2001. He became a star here and a legend back home. And regardless of whether or not they were baseball fans, many Korean Americans across the country made it a ritual of ethnic pride to cheer for Park whenever the Dodgers were in town.

Andy J. Kang, 32, was a catcher for South Pasadena High School’s baseball team in the late ’90s and grew up idolizing Korea’s pioneering big leaguer. Over a decade later, he saw Ryu make his major league debut in April from the same reserve-level seating at Dodger Stadium.

“I’m so proud to see another Korean pitcher as a full-time starter for a major league team for the first time in over 10 years,” Kang says. “I’m proud and excited.”

Both Korea and Korean America have grown tremendously since the late ’90s, when Park was viewed as a national hero. Korea is no longer a country mired in the IMF economic crisis. The population of Korean Americans has increased by 46 percent from about 800,000 in 1990 to 1.7 million in 2010, according to the U.S. Census.

Along with growth comes higher standards, of course, and Ryu, in his first season, is already expected by many to surpass Park’s legacy. Many in the Korean American community are counting on him to prove that their ancestral homeland can now churn out better product than ever.

“I am not even a baseball fan,” says Jason Seung Lee, a recent college graduate who lives in Koreatown. “But I’m interested in the Dodgers now, and I’ve already started checking their schedule because I know Ryu is with the team. I just want to see him get 10 strikeouts per game.”

Martin Kim was a part of the Dodgers’ front office well before they signed Ryu. Once Ryu was on the

Dodgers’ radar, one of Kim’s tasks became compiling a package of weekly reports about all aspects of the player, covering his performance as a ballplayer and even his actions off the field. After following Ryu religiously, Kim says he’s not surprised to see how quickly the Korean American community has gotten behind the rookie.

“As a fan, when you see [Ryu’s] dominance in Korea, at the Olympic Games and even at the World Baseball Classic, … the excitement comes naturally when you see that level of success being transformed here to the major leagues,” Kim says.

This is not to say that Koreans, as enthusiastic as they have been, are his exclusive supporters. Despite his early faux paus at Dodger Stadium that earned him jeers (and for which Ryu later publicly apologized), the rookie with the sizable price tag has gradually been winning over many a fan not only with his performance on the mound, but just as much with his upbeat conduct off it.

“He’s always having fun,” says former Dodgers infielder Luis Cruz, who was one of Ryu’s closest friends on the team before the Dodgers designated him for assignment in June. “Even if he doesn’t speak English, or Spanish, he tries to communicate with everybody, to Kershaw, to Hanley [Ramirez], to me, and everybody else. I remember the first time I came to the States from Mexico, I didn’t speak any English. I know how hard it is.”

Having a full-time interpreter in Kim alongside him at all times certainly helps, but there’s also a deliberate effort, say his teammates.

“Not having fear,” Dodgers first baseman Adrian Gonzalez says, when asked how Ryu was able to form a close bond with his teammates despite his limited English. “A lot of international players are fearful of not being understood or having trouble with communicating. But Ryu’s always trying to learn Spanish, trying to learn English, and sometimes even teaches us Korean. He’s a fun teammate to be around … and everybody likes him.”

Despite early concerns some observers may have had about his ego, given his sizable paycheck and reported contractual demands, Ryu’s showing he’s a team player through and through. During the first half of the season, every time the Dodgers bullpen, defensive errors or subpar run support stripped him of a possible winning opportunity, Ryu would tell reporters, “There will be more games I’ll win because of my teammates.”

Ryu can’t help but burst into laughter when asked where his positive, colorful personality comes from. “Nowhere,” Ryu answers, chuckling. “Really, there’s nothing to it. That’s just the way I am.”

***

But there is something distinctly different about the way Ryu is.

The likes of Park, Shin-Soo Choo and Hee-Seop Choi got a shot in the major leagues after being handpicked by American ballclubs as prospects out of Korean universities, only to bounce around the minor leagues for years as they had to develop and be tailored into “proper” big leaguers. Until Ryu, the sentiments around the major leagues have been that teams here are better off going after youngsters out of high schools and colleges in Korea, and developing them, rather than signing professional players who’ve already become stars in the KBO. In other words, professional baseball in Korea simply didn’t have high enough standards to produce ballplayers capable of making an immediate impact in the major leagues.

“Teams in the major leagues are paying more attention to Korean baseball now,” Ryu says. “If it weren’t for Korea doing so well on the international stage, it would’ve taken a lot longer for us to get attention.”

But he adds, “To be honest, people here still rate Japanese baseball higher than Korean baseball. And I’m the first player to come straight into the major leagues from the KBO. If I do well here, that will change America’s view of Korean baseball. I understand that.”

And, so when he demands things, like the right to block a minor league assignment (a right no other Dodgers pitcher has), it may sound like arrogance, but there’s more to it.

“I wanted to get the best treatment possible,” Ryu explains. “Because if the treatment I get here was too disadvantageous, it would result in negative consequences for Korean players who would follow my footsteps in the future.”

What Ryu is trying to prove in the major leagues goes well beyond a game of baseball. He’s striving to prove the idea that Koreans are no longer desperate to simply be seen or heard. Today, they are ready to shine on the world’s biggest stage. And just as Ryu inherited a legacy left for him by Park, he knows he is also paving a path for other ballplayers from his native country.

And he seems to be the ideal person to help shift how Koreans are perceived, not only because he has the talent, but also because he seems to embrace playing that role.

“I had a long talk with him,” says Kim. “I told him, ‘When we go to places like Atlanta, D.C., San Francisco, there are Korean folks who come just to see you, wearing your uniform. You’re giving them a lot of hope. There’s this huge sense of pride because of you.’ And he totally gets that. He understands it.”

Mattingly takes it a step further, saying that Ryu has the fortitude to use even the brightest spotlight—the greatest expectations—to help him perform at a higher level on the mound.

“It seems like he likes all of this,” Mattingly says. “And I think that’s a good thing. Obviously he’s very popular in L.A., where there’s a good Korean market, but it seems like everywhere we go, whether it’s New York or Atlanta, the Korean community always comes out for him. And he seems to be enjoying it and looks to get the big out when the place starts getting noisy. It doesn’t seem like he takes it as an overmatch. He enjoys it.”

Swagger? Nah. He’s just having a ball.

___

This article was published in the August 2013 issue of KoreAm. Subscribe today! To purchase a single issue copy of the August issue, click the “Buy Now” button below. (U.S. customers only. Expect delivery in 5-7 business days).